The Night Watch: Will Gompertz reviews the Rijksmuseum's high tech photo ★★★★★

- Published

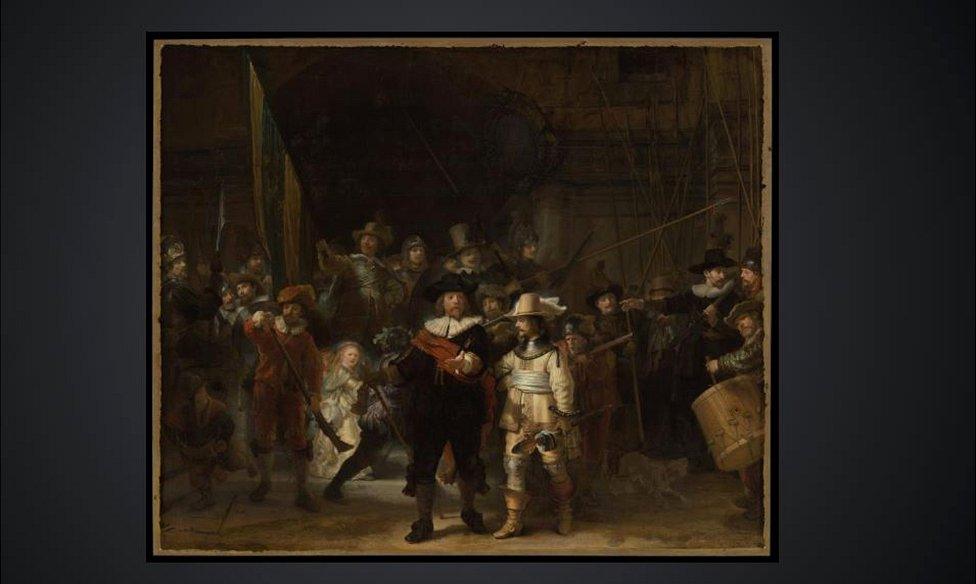

At 9am on Tuesday the Rijksmuseum in Amsterdam posted an image of Rembrandt's The Night Watch (1642) on its website. Nothing particularly unusual about that, you might think. After all, the museum frequently uploads pictures of its masterpieces from Dutch Golden Age. But there was something about this particular photo that made it stand out just like the little girl in a gold dress in Rembrandt's famous group portrait of local civic guardsmen.

The web image presents the painting unframed on a dark grey background, external. It looks sharp and well-lit but not exceptional in terms of photography.

Until, that is, you click on it, at which point you're zoomed in a bit closer.

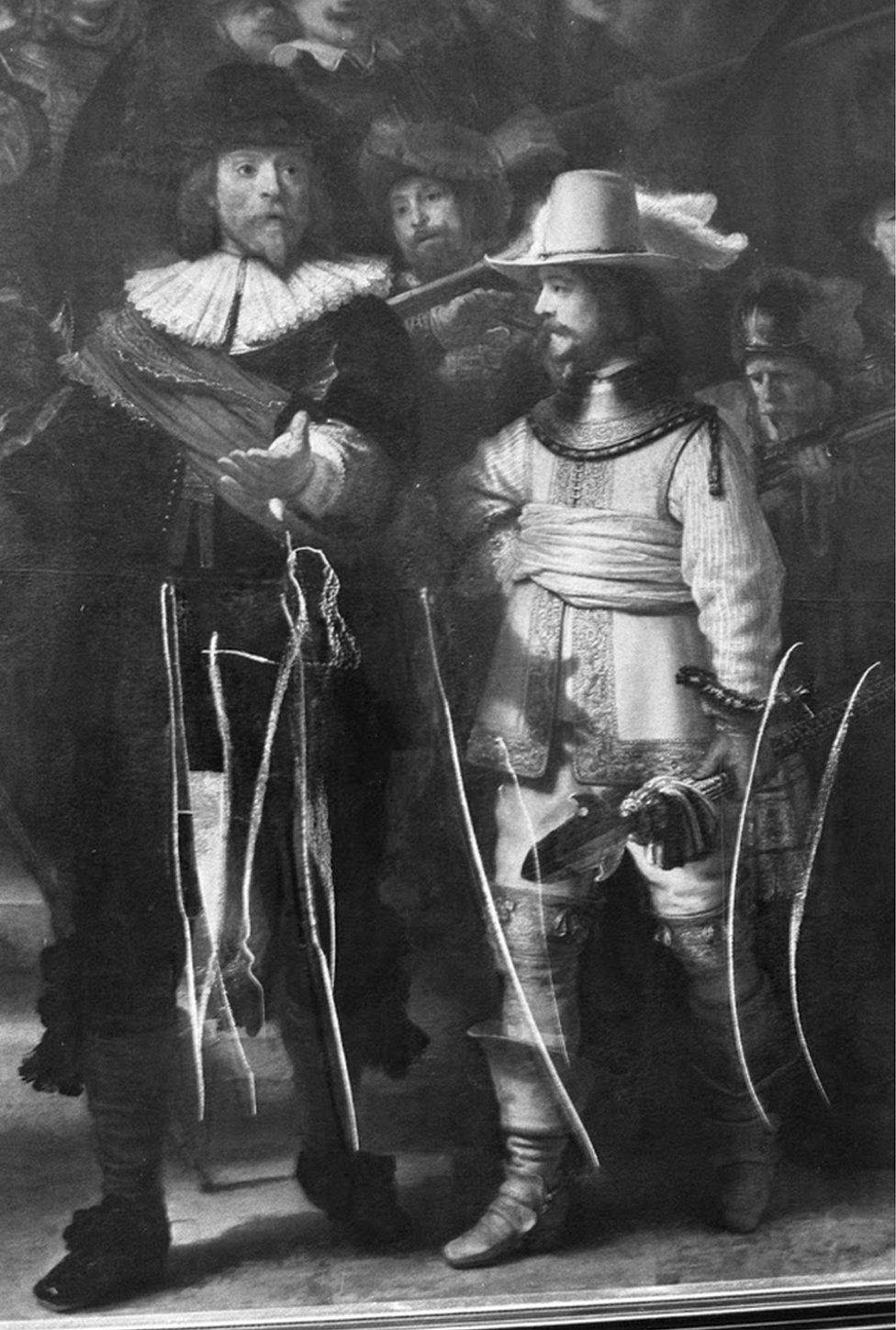

Click again and you're propelled towards the outstretched hand of Captain Frans Banninck Cocq. Another click, and you're face-to-face with the leader of this group of not-so-merry-men.

Once more, and you can see the glint in his eye and the texture of his ginger beard.

At no point does the image start to pixelate or distort, it's pin-sharp throughout.

And it remains so as you continue to click, getting further and further into the painting until the Captain's paint-cracked eyeball is the size of a fist, and you realise that tiny glint you first saw isn't the result of one dab of Rembrandt's brush, but four separate applications, each loaded with a slightly different shade of paint.

Researchers used the very latest technologies to allow every detail to be seen by the naked eye, without any picture distortion

And then you stop and think: Crikey, Rembrandt actually used four different colours to paint a minuscule light effect in the eye of one of the many life-sized protagonists featured in this group portrait, which probably wouldn't be seen by anybody anyway.

Or, maybe, this visionary 17th Century Dutchman foresaw a future where the early experiments with camera obscura techniques, in which he might have dabbled, would eventually lead to a photographic technology capable of recording a visual representation of his giant canvas to a level of detail beyond the eyesight of even the artist himself!

It is, quite frankly, amazing.

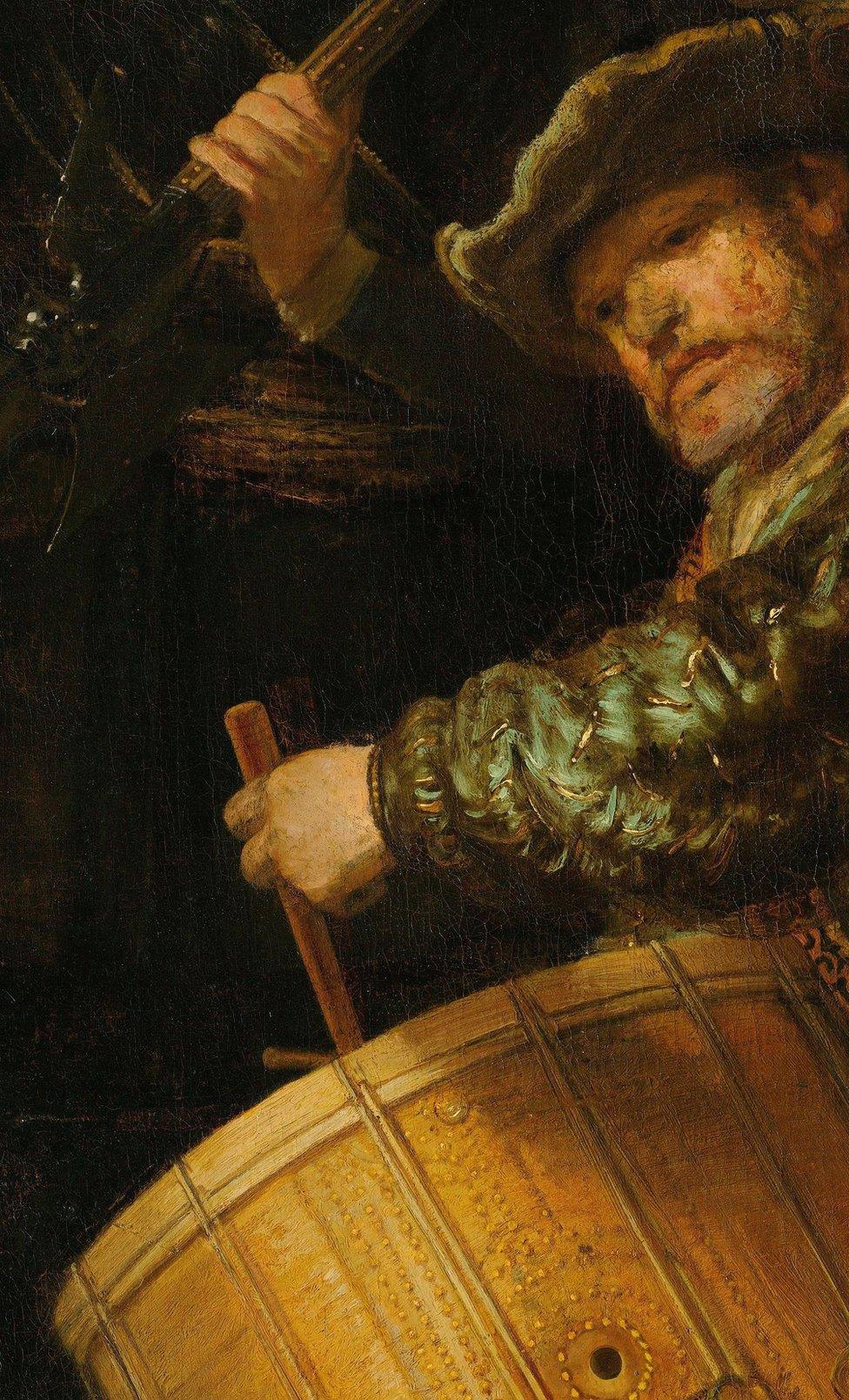

For instance, I've always liked the ghostly dog that turns and snarls at the drummer situated at the edge of the painting. I'd assumed the hound was unfinished and therefore unloved by Rembrandt, but now I can see by zooming in that the artist not only gave the dog a stylish collar, but also added a gold pendant with a tiny flash of red paint to echo the colour of the trousers worn by the drummer.

Clearly, Rembrandt was pro-dogs.

In the lower right corner you can see a dog barking, but the deterioration of the paint has given the dog a ghostlike appearance

As always there is artifice behind the art, as you will see within moments of zooming into The Night Watch.

It quickly becomes apparent that Rembrandt first created his wonderfully dynamic composition, and then fine-tuned it as he went along. You will spot lots of small shadowy corrections (pentimenti) he made, such as the top of the drummer's stick on the far right, or on the index finger of the Ensign holding the Troop's flag aloft.

There is artifice in the photograph, too. It is not a single image as it appears, but a composite of 528 individual digital photographs that have been seamlessly stitched together to give us a completely new view of one the most famous paintings in western art.

Let's zoom out for a moment.

The largest and most detailed photograph of The Night Watch allows people to zoom in on each brushstroke and even particles of pigment

Rembrandt signed, dated and called his painting: Officers and Men of the Amsterdam Kloveniers Militia, the Company of Captain Frans Banninck Cocq.

It was a commissioned portrait by the Kloveniers Militia (a sort of Dad's Army of locals) to hang in their HQ. Those featured (probably 18 members originally) each paid to be included. Capt Cocq takes centre stage, with his trusty Lieutenant Willem van Ruytenburch to his side. The men gathered behind them are carrying an assortment of weapons with which to defend their neighbourhood.

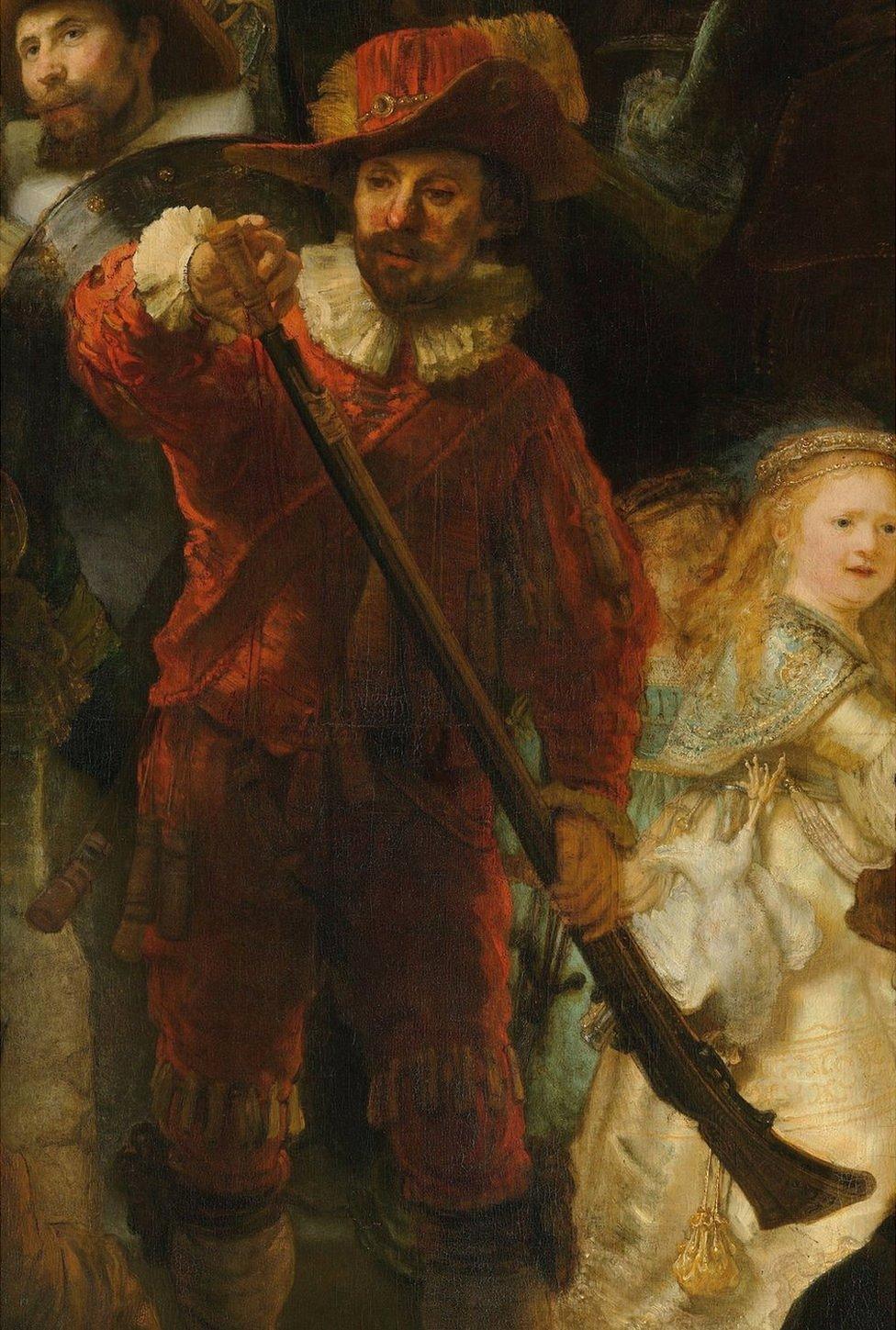

Muskets (Klover) were their speciality, a point Rembrandt illustrates with a surreal sequence running left to right across the picture featuring three musketeers. The first, dressed in red with white collar and cuffs, is loading his musket with gunpowder. The second, a young boy, partially obscured by Cocq's right arm, fires his gun, ruffling the feathers of Ruytenburch's hat but not the man himself, who one has to assume is stone deaf. And then, there's the third, an older man also dressed in red, blowing away the spent powder from the fired gun.

The young girl in the gold dress is not a member of the militia, but is there as their shining symbolic mascot. The upturned feet of the dead chicken hanging from her belt represent the Kloveniers' golden claw emblem.

The painting initially hung with several other huge group portraits, giving visitors to the troops' inner sanctum the sense of being surrounded by local muscle. It was subsequently moved in 1715 to the Town Hall on the Dam (now the Royal Palace), where it was trimmed on all four sides to fit between the doors.

It was first called The Night Watch in 1897, when the varnish applied to protect the paint had become so old and stained the picture looked like a nocturnal scene.

That layer of varnish was removed long ago in one of the 25 or more restorations and treatments The Night Watch has undergone over the years.

The most memorable being in 1975 after a visitor to the museum attacked the painting with a knife, causing severe damage, traces of which you can see when you zoom in on the new composite photograph: An act of art historical sleuthing which is the digital photo's primary purpose.

The Night Watch was badly damaged in 1975, after a man attacked the painting with a knife, inflicting 12 cuts to the canvas

The Rijksmusem's Operation Night Watch team resumed their work this week on the restoration project

The 44.8 Gigapixel image was created for the Rijksmuseum's conservation department, which is currently embarked upon the most exhaustive facelift The Night Watch has probably ever endured.

It enables the team of 12 to look right into the picture without using microscopes, in order to see what work needs to be done.

A huge amount is the answer.

1. This shows a little tassel hanging from a cord on the left shoulder of Lieutenant Willem van Ruytenburch (dressed in yellow).

2. The camera zooms in to show details of the individual blue and white threads, with signs of visible degradation.

3. The camera has zoomed in at ultra high resolution, to reveal minute cracks running through the paint's surface.

Zoom in and you'll detect plenty of cracked paint, which is to be expected. But zero in on the Captain's and Lieutenant's faces and you will notice they're covered in blackheads. That's not because they didn't know one end of a bath from the other - they were sophisticated chaps - it is probably down to aging white paint particles, the tops of which have broken off to reveal a dark inner. There are thousands of these pinprick blemishes, all of which conservators should be able to reverse, bringing an even greater liveliness to an already lively painting.

The Night Watch is an incredible work of art.

Soon, you will be able to stand in front of it once again when the Rijksmuseum re-opens on the 1 June (caveat: there will be vastly reduced number of admissions, and The Night Watch is currently encased in a glass box - still visible but not as approachable). And if and when you do see it for real, you will immediately notice Rembrandt's exaggerated use of light and shade to create a sense of drama, aided and abetted by an all-action composition emphasised by teaming diagonal lines.

The Night Watch is as close to theatre as a painting can get.

As the director of the Rijksmuseum said, it is a school photo taken before everybody is lined up in order (it shows Capt. Cocq instructing Lt. Ruytenburch to bring his men to attention).

It captures a moment of movement and mayhem.

You can see that when in front of the canvas. But when you are not, when you're at home, you can now see the same sense of chaos in the way Rembrandt painted his masterpiece, made when he was at the peak of his fame, just at the time his beloved wife was dying and his life took a turn for the worse.

Self-portrait as the Apostle Paul, Rembrandt van Rijn, 1661

The further you look into it the greater the mess appears to be. Splodges of impasto paint here, unfinished transitions there. It's a mixture of early Rembrandt tautness and late Rembrandt looseness.

If you thought Van Gogh or Jackson Pollock invented expressionistic painting, you'll think again when you've zoomed into The Night Watch.

It is a sight to behold. A magnificent sight, which extends our knowledge of a truly great work of art, whether you're an old timer or a first timer.

New technology is often used to try to jazz up old art, which is generally a bad idea. But, the Rijksmuseum is using technology to increase our understanding and appreciation of a Golden Age great, and that is a good idea. As you can see.

Recent reviews by Will Gompertz

Follow Will Gompertz on Twitter, external

- Published2 March 2019