William Blake: Biography offers glimpse into artist and poet's visionary mind

- Published

Few took William Blake seriously as an artist and poet in his lifetime

One day in 1801, when William Blake was living on the Sussex coast, he went on a long country walk when he got into an argument with a thistle.

The artist, poet and musician, who experienced beatific visions throughout his 69 years on Earth, wasn't wandering lonely as a cloud, like some of his Romantic peers.

On this occasion, the prickly plant he encountered also took the form of a hectoring old man. For all Blake could see, the two were inseparable.

The London shopkeeper's son (who didn't go to school) would also regularly see God, angels and demons, and often spoke with the spirit of his dead brother Robert. His wife Catherine once commented: "I see very little of my husband, he's always in paradise."

These divine and mind-bending experiences informed Blake's world view and inspired his deeply philosophical illustrated texts like Jerusalem and Milton.

As a result, though, he was deemed mad by much of 18th and 19th Century England, and died penniless and largely unheralded.

Nowadays, he is widely considered one of UK's most influential and respected artists and poets. And in a new biography, William Blake vs the World, author John Higgs argues we are now far better placed to understand what was going on inside his head.

'Mythological system'

"Blakeans have been touchy about the subject historically," Higgs tells the BBC. "There was the one exhibition he gave in his lifetime and it sold no paintings, and it got one review which referred to him as 'an unfortunate lunatic'. And so this accusation of madness followed him around in his day.

"Van Gogh scholars are quite happy to admit he had mental health issues, and that adds to their understanding of him. [But] Blake scholars have been traditionally keen to insist that he was not mad, that there is reason and logic and worth in this system that he created - this mythological system."

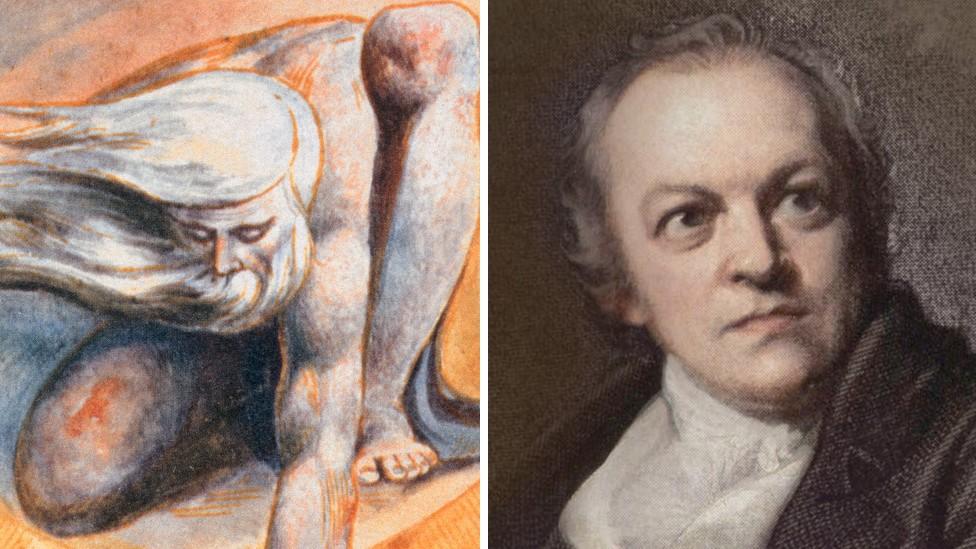

A portrait of Urizen, the embodiment of restricted thought, reason and law, from William Blake's The Book of Urizen

He adds: "I think now we're in a position where we can say, yeah absolutely he was [sane]. But there was a period where he had poor mental health. In his letters there were references to melancholy, as a disease, and depression, and also later incidents that show signs of paranoia."

Those mental health issues arose around the year 1800. "It was just a period in his life and you can see at the end of his life how he had come through it, with the help of his wife, and was just in a very blissful state," Higgs continues.

Blake's high regard for contrary states, as evidenced in his Songs of Innocence and Experience and The Marriage of Heaven and Hell, suggests he knew that what goes up must come down.

Slip inside the eye of your mind

The key to achieving timeless bliss, he believed, was to re-balance the imagination (or The Four Zoas) so the left-brain - the part that deals with logic, reason and language - was less dominant, unlocking the potential of the right side, which deals with creativity, emotions and physical pleasure.

The polymath underlined the importance of viewing things through one's mind's eye, rather than merely through the organs on either side of your nose. In his book, Higgs cites the work of neuroscientist Dr Adam Zeman, who has studied the imagination for decades. He first described in 2015 the condition of aphantasia, where some people were found to be unable to visualise mental images. In other words, they had no mind's eye.

At the opposite end of the spectrum, those with extremely vivid imaginations were said to have hyperphantasia.

Dr Zeman, who released his latest research findings, external last month - with the help of his colleagues at the University of Exeter and around 70 volunteers willing to have their brain activity scanned - agrees with Higgs that rather than meaning he was unhinged, Blake's visions strongly suggest hyperphantasia.

"When I think about my fiancee, there's no image" Niel Kenmuir on living with aphantasia

"[Blake] seems to live in the world of his own imagination to a great degree," Dr Zeman says. "Some people [with hyperphantasia] say that it is hard for them to be sure whether they've imagined something, or it actually happened because their imagining is very vivid."

Neither extremes, which are believed to affect millions of people around the world, are viewed as disorders, he notes. They are more like interesting variations of perspective, each with their own pluses and minuses.

Hyperphantasics tend to be more open and have abundant mental imagery, research shows, but can be more vulnerable to emotions that images fuel - like regret, disgust or longing.

Aphantasics tend to be more introverted, have thin autobiographical memoires - relying more on facts - and often miss being unable to picture loved ones they have lost. However, many highly imaginative people, including Pixar animations co-founder Ed Catmull, Mozilla Firefox co-creator Blake Ross and leading scientists Oliver Sacks and Craig Venter have all lacked imagery.

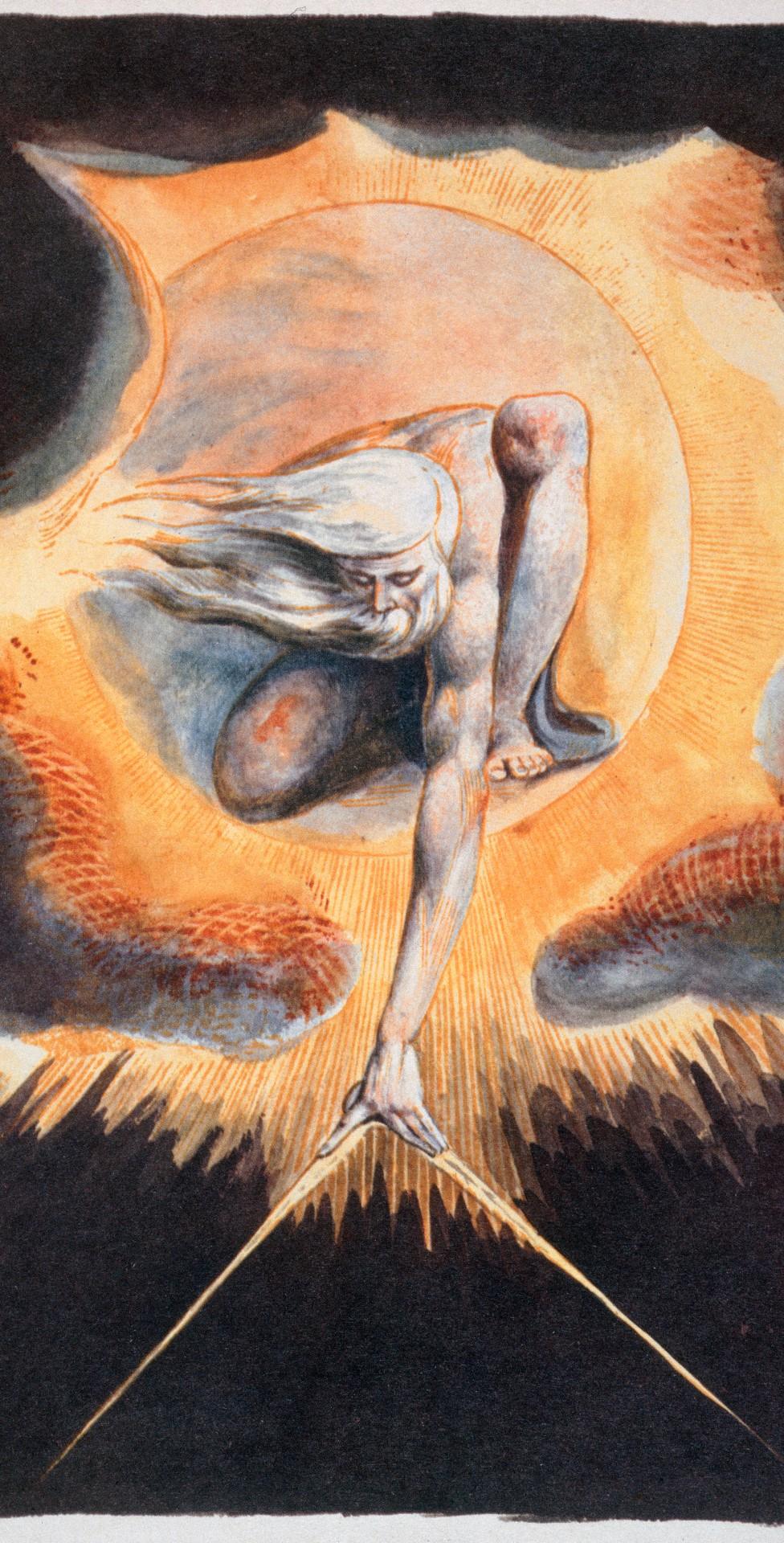

Urizen measures out the material world in The Ancient of Days, taken from Europe a Prophecy by William Blake

There is some evidence to suggest that very vivid imagery can put people at the risk of psychosis, Dr Zeman says, if they lose sense of the boundary between what's real and what's imaginary - which Blake's contemporaries clearly thought he had done.

But he thinks Blake, who died almost 200 years ago, may have been an early adopter of the increasingly accepted idea in psychology and cognitive neuroscience today that "all our experience, in a sense, is imaginative".

"Although we aren't aware of it, a huge amount is happening in our brains all the time to enable us to see, hear or make sense of anything," Dr Zeman says. "An experience itself is a creative act, let alone the echo of experience that you get in the mind's eye.

"I think Blake had a sense that all of all our whole mental lives - not just the mind wandering, daydreaming, creativity and the artistic sense, but simply having an experience - is a creative and imaginative act."

Or as Blake himself put it: "The imagination is not a state: it is the human existence itself."

Albion contemplating Jesus crucified in William Blake's engraved poem Jerusalem

The limited, rational or logical part of our brains, which Blake characterised as Urizen, is actually only a model of how we understand the world, Higgs explains.

"We think it's real, we think it's true," he says. "When it feels under threat, it lashes out and tries to defend itself.

"You can see on social media, people have a desperate need to be thought of as right. For Blake, it's all about being able to step outside that and just see the rational brain for what it is, as a sort of quite limited small part of a much larger mental experience."

Albert Einstein once remarked on "the stubbornly persistent illusion of the passing of time", which was also depicted by Blake in the form of Los.

The artist's conviction that concepts like time, God, heaven and hell were all internal creations, Higgs feels, also salvages theological debates for today's more secular UK society.

"If you know someone who has been living through hell, the idea that Blake was in paradise becomes a little bit more plausible," he says.

The doors of perception

William Blake is by no means the only historical figure to have reported on such ineffable experiences. And his apparent capacity to access parts of the imagination that were beyond the realm of the average person, and the importance he placed on free love, sex and bashing the establishment, were of great appeal in the swinging late 60s.

Jim Morrison's band The Doors even named themselves after a famous line from a Blake poem: "If the doors of perception were cleansed then everything would appear to man as it is, Infinite."

The Doors attempted to break on through to the other side

The likes of Timothy Leary and Aldous Huxley championed the use of psychedelic drugs to help achieve Blake-like states of consciousness.

For people with aphantasia, Dr Zeman notes, hallucinogens sometimes help them to generate imagery, but it doesn't seem to outlast the drug effect. Higgs compares the practice, as well as that of transcendental meditation, to "micro-dosing in Blake's eternity".

It's not impossible that Blake may have dabbled in magic mushrooms, the author concedes, but recreational use was not believed to have been common at the time, and he had been chronicling his visions from childhood until old age.

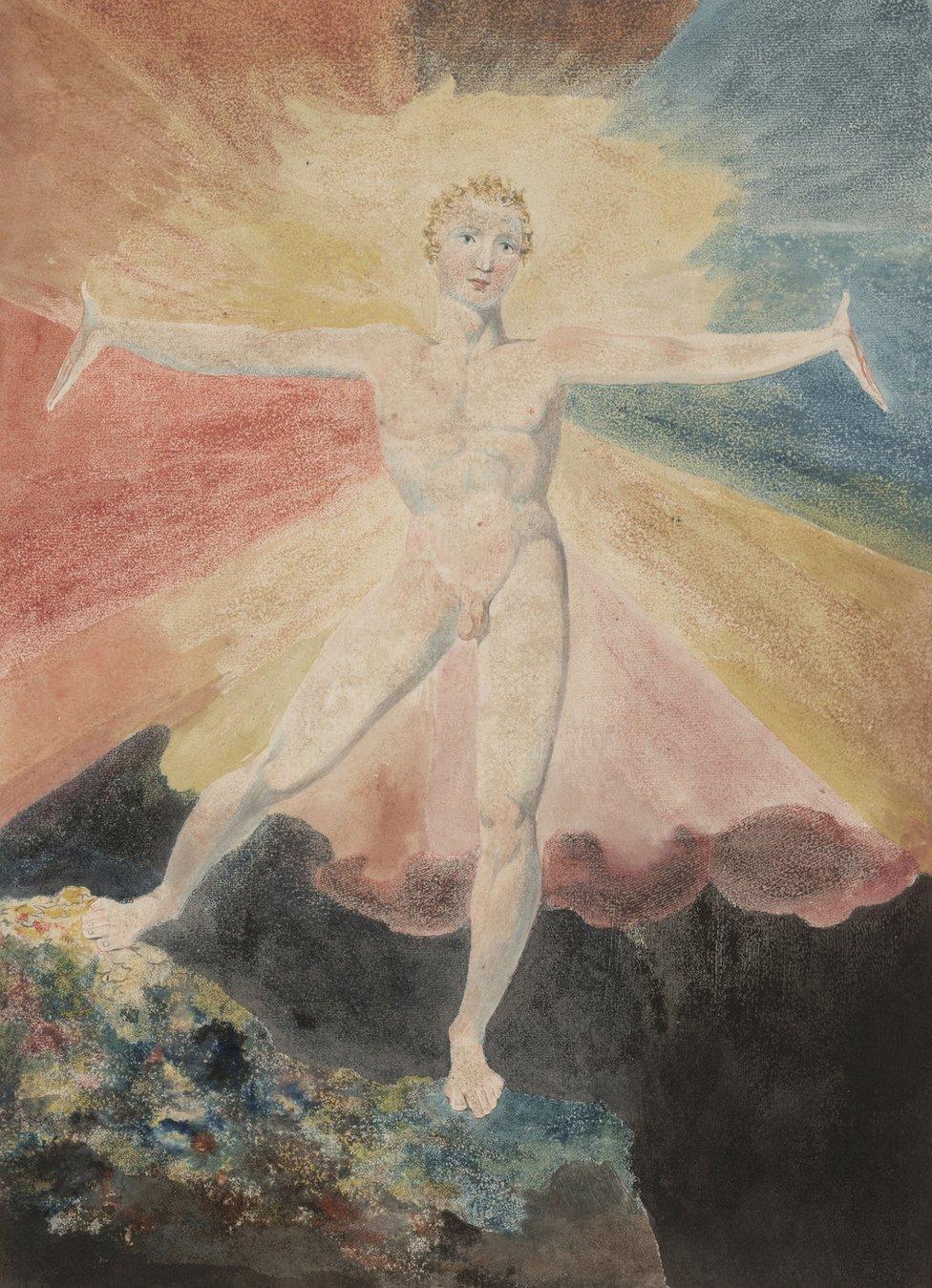

William Blake's Albion Rose, circa 1793

Blake believed we could all work on our imaginations, just like our abs or biceps, and aspire to joining him in "eternity".

Dr Zeman's studies suggest that while it may be possible to strengthen the mind's eye, ear or fingertip with magnetic pulses, there is a biological and possibly genetic limit to how far along the imagination spectrum each individual can travel. But we should celebrate that difference, he says, and not medicalise it.

He is hopeful that one day we will be able to know it better, and ultimately solve the age-old Cartesian conundrum of how consciousness can be generated from that grey, jelly-like lump of tissue in our heads.

To give Blake the final word on the matter: "What is now proved was once only imagined."

William Blake versus the World, by John Higgs, is out now

Related topics

- Published14 September 2019

- Published26 August 2015