Germany conflicted on how to handle Brexit

- Published

Seat of power: Politicians at the Reichstag are watching the debate closely

The head of the Berlin Stock Exchange, Artur Fischer, looks on happily as children run around and splash in the swimming pool at Berlin's international club.

Our talk of dark times when the city smouldered seem out of place on this sunny day amid the greenery and sounds of laughter.

But the possibility of Brexit makes him think of a time when Berlin was a ruined city, his father's horrendous experience as a 15-year-old boy soldier and Germany's past.

"Being nationalistic is not a good thing. So if the value of the EU is damaged - and it is already fragile - and if Great Britain is out, the temptation is the German population will also consider 'what are the benefits? Why don't we do things on our own?'

"It gives you a very eerie feeling, how thin that layer of civilisation is. If you do things together with other countries in the EU it gives us a chance to come to a compromise. If we are not in the EU we will not look to compromise, but to win."

It is a reminder that the European Union means more emotionally to Germany, and many other members, than it ever can do to the UK.

It is ironic that if we do vote to leave the EU the internal politics of the institution and its member nations could matter more than ever before for the future of our country.

Talks have already started, external in Brussels about how to respond if we do vote to leave.

After initial bromides about building a stronger Europe they would wait for the UK Government to set out the terms it might want.

There might be a wait, if, as expected, the Conservative Party descends into civil war, external.

But the future might then hang on the reaction of the 27 remaining countries of the EU.

Leave campaigners constantly argue that because of the size of our economy the EU wouldn't raise trade barriers, external, and cut off their nose to spite their face.

Remain campaigners, on the other hand, warn that the rest of the EU wouldn't make it easy, external.

German power is the real key to Europe

EU referendum: Where are the big themes?

Two main forces

In reality two main forces would be in play on the continent, competing with each other.

One is the instinct that it is indeed best for the European economy and European companies to have a smooth transition to an easy relationship. The other, that breaking up cannot appear pain-free when there are so many pressures on the EU.

What Berlin and Angela Merkel wants, does not always, automatically, become EU policy. But it has a powerful influence. That is why I went to Berlin.

Christian Ehler warns sorting out Brexit could be a nightmare

When I meet the Christian Democrat, external MEP, Christian Ehler, he is wearing cuff links: one says "trust me", the other "I'm a politician" .

He can afford this wry gesture. He is not just a politician - he's also an industrialist, former MD of a multi-national biotech company.

He knows Mrs Merkel well, and has an important job in the European Union - coordinator for his party grouping on the industry committee.

He told me: "Politicians like to pretend they are in charge of everything. But it is not just a political decision."

The UK could get a good deal with minimal rules, he said, but it would have no say over the rules, and so wouldn't be integrated into the EU market: that could harm the British economy.

Alternatively, the EU could impose tough measures on the UK, but that could cause damage on all sides.

Would Vladimir Putin benefit from Brexit?

"Sorting it out would be a year-long nightmare, the economy (across the Eurozone) would go down by at least 3 to 5%."

Mr Ehler is frustrated. His boys at are at a British school, he has a flat in London and he travels there often and says that the economies are so linked via the EU that it would be difficult to disentangle.

"It is really complicated. It's an integrated economy. Take my constituency: one of the biggest employers is Rolls Royce, which is producing half of the engines for Airbus in Germany.

"Should we put the British out? Then my constituency is out."

Mr Ehler's committee has looked at what would happen to joint investments, such as this. His conclusion? It is a mess, a nightmare that "would have Putin laugh his butt off".

He reminds me that some of Germany's success is in part down to the structures the British put in place after the war, not least a system of industrial relations.

There is almost a sense of embarrassment at the way people almost seem to be flattering our awkward country.

Widespread irritation

But then there is a also widespread irritation that the British are more inclined to moan about being dominated by the EU than celebrate their leadership within it.

I hear several influential people argue that Germany needs the UK to push - against the French and others - for economic liberalisation.

Without the UK, Germany would be cast more firmly on one side of the debate, rather than as honest broker, which makes them feel more comfortable.

But this is mere detail to the fear that grips mainstream politicians all over Europe. The hard-right Front National will be fighting an election in France next year on the policy of a referendum on the EU, external.

Parties which question the European project are on the rise in Austria, Sweden, the Netherlands, the Czech Republic and Italy - just to mention the most obvious examples. Nationalistic governments in Hungary and Poland are happy to clash with Brussels.

The director of the German Marshall Fund's Europe programme Daniela Schwarzer tells me: "One motive (if the UK leaves) will be to not make others think this is an easy game - you have a referendum and you get what you want. There has to be a visible cost to leaving the European Union."

Germany - mindful of its dreadful past - has always preferred to exercise power through the EU, in concert with others. As the generations change this instinct becomes a little weaker.

The Greek crisis on one hand, and the migrant crisis on the other, has brought Germany's role into sharp focus, and underlined the fragility of the EU.

The rise of the right has been seen in Germany too. The Alternative for Germany (AFD) is only three years old but did well in regional elections, external.

Beatrix Von Storch, party vice chair and an MEP, tells me if the UK votes to leave it would be bad for Germany in one way - it would pick up the tab if our contributions, external disappeared.

But she adds: "It would be good if you leave just to show you can survive. We're told no one can live without the European Union - you cant trade, you can't travel, everything will break down and the UK will go bankrupt in a month or two.

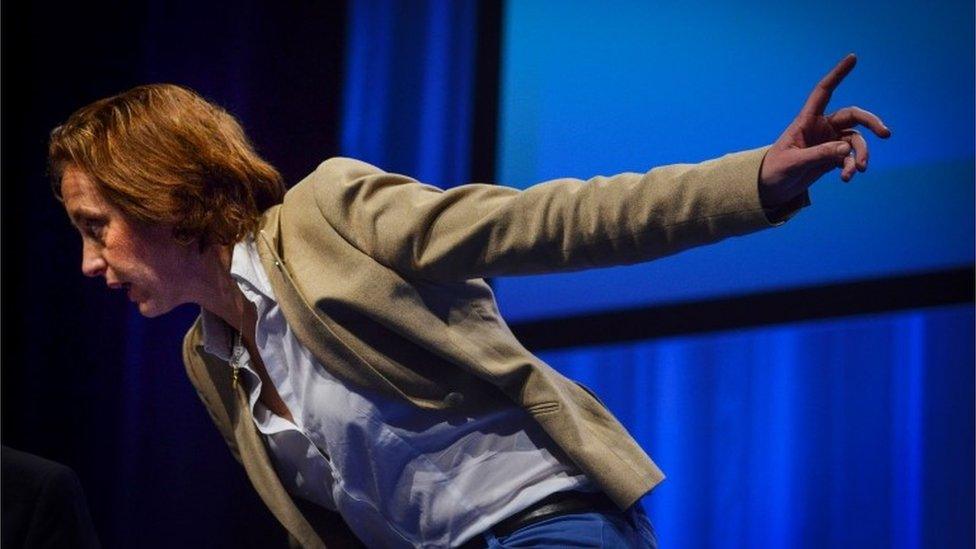

Beatrix von Storch hopes that the UK quits the EU

"I think that's complete rubbish and I would like to see how it works and I think we will see it is possible to trade with EU without being part of it."

She says making life tough for Britain would be counter-productive.

"If they start to punish the UK this would strengthen all the movements that want to leave the EU, the movements we can see rising at the moment."

Artur Fischer says Brexit would inevitably lead to confusion.

At present he works two days a week in London, and pays 40% of his taxes in the UK. He doesn't know if that would continue. His board knows any deal with UK companies is currently covered by EU rules - they might not have that certainty in the future.

"Our industry would be against any trade barriers. They are against all trade barriers.

"But I'm pretty sure from a political point of view that after they left Britain would not have the benefits they currently have."

People may yearn for certainly in this debate - the reality is there can be none, because it depends on future moves and counter-moves.

If the UK does leave, the arguments I've been hearing in Berlin will rage across a continent.

- Published28 April 2016