Plastic pioneers: How war has driven surgery

- Published

Dr Andrew Bamji talks about the work of plastic surgeon Sir Harold Gillies.

A curator removes the lid from a brown box in the archives of a museum at the Royal College of Surgeons.

Inside, wrapped carefully in tissue paper, is the cast of a man's face.

The soldier was one of thousands who received devastating facial injuries during World War I.

Where once his nose would have been there is only a strange indentation, like a thumb pushed into dough.

The cast was made to help a medical team, led by plastic surgeon pioneer Sir Harold Gillies, work out how to repair the man's face.

As Dr Andrew Bamji, a medical doctor and former curator of the Gillies archive explains, the war led surgeons to attempt ground-breaking procedures, which paved the way for modern plastic surgery.

"When you are trying to devise techniques for things that have never been done before, you have to experiment, and you experiment in different ways," he says.

"You try different techniques, but by pulling everyone together into the same place, everyone has the opportunity to learn."

Dr Harold Gillies set up a multi-disciplinary team of surgeons, nurses and artists at what was then the Queen's Hospital in Sidcup, south-east London.

The artists took casts of the men's faces and recorded their injuries in meticulous detail as portraits, before the days of colour photography.

Sir Harold Gillies (far left) developed new medical techniques to reconstruct the faces of WWI soldiers

The team worked together to try to repair the devastating injuries of war, using grafted flaps of skin and transplanted rib bones.

One of the sculptors who worked alongside surgeons at the Queen's Hospital, taking casts of the men's faces, was Kathleen Scott, wife of Antarctic explorer Captain Robert Scott.

Almost a century later, her granddaughter, Louisa Young, has written a novel based around the work at Queen's, now Queen Mary's Hospital, Sidcup.

"She was a sculptor and she was working with the surgeons by making casts of the wounded and scarred faces for the rebuilding," explains the novelist.

'Poetry' of art

Young's protagonist, Riley Purefoy, is fictional, but he is inspired by one of the portraits made by Sir Henry Tonks of some of the wounded soldiers.

Tonks trained as a surgeon but chose to follow a career as an artist. He encouraged students to combine anatomical study with an appreciation of what he called the "poetry" of drawing.

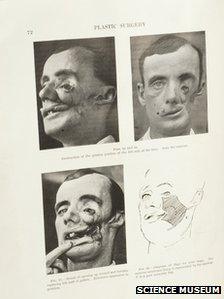

A page from Plastic Surgery of the Face by Harold Gillies

While in some ways his paintings are medical records, they also capture something very human; a glimpse of the horror that many war veterans hid from the world.

Louisa Young says memoirs written by a matron at the Queen's Hospital provided further ideas for the story.

"She reported this anecdote about a young man who, having suffered a horrible facial injury, rejected his girlfriend.

"He told her he had fallen in love with someone else. And that was very interesting - whether he was being honourable and gentlemanly or whether he was being arrogant and presumptuous - and what she might think about that, and how they might proceed in that situation.

"And they were all terribly young - the way you are living your life and have hardly had a chance to start your life and then history comes and throws everything up in the air and you land broken - and then what?"

Now, the Gillies collection is being catalogued and restored to go on display at the Hunterian Museum within the Royal College of Surgeons in central London.

The archives gathered during the war include medical case notes, paintings, plastic casts, surgical instruments and teaching aids.

They are powerful testimony to the advances made by modern surgeons in the past 100 years.

As Louisa Young explains: "Now we're terribly good at fixing things up. Modern maxillofacial surgery is stupendous. It's astounding what they can do."

The novel, My Dear I Wanted To Tell You, has been nominated for both the Wellcome Trust Book Prize, celebrating medicine in literature, and the Costa Book Awards.

- Published18 November 2011