Shenley Hospital: Life under observation

- Published

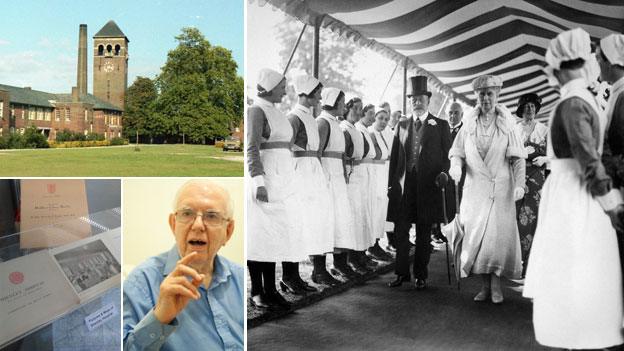

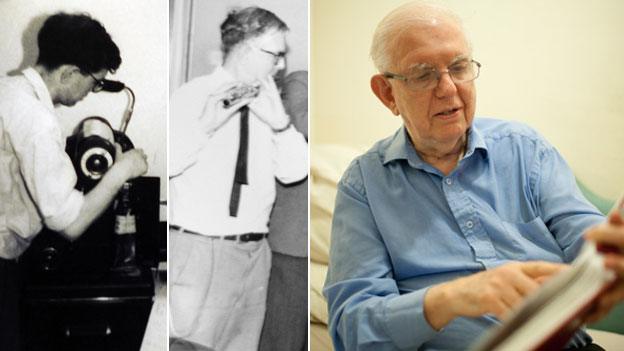

Shenley Hospital, opened by royalty in 1934, housed thousands of patients for more than 63 years

A new online exhibition reveals how Shenley Hospital was one of the most ground-breaking mental health institutions of its time. To its former patients and staff, the hospital's experimental ethos is remembered for both good and ill.

From the day it opened in 1934, Shenley Hospital in Hertfordshire was always intended to be at the cutting edge of mental health care.

Patients were used as guinea pigs undergoing a variety of experimental treatments - including malaria fever therapy to cure "insanity caused by syphilis", electro-convulsive therapy and insulin injections to induce comas.

In 1962, it became one of the first hospitals to host a mother-and-baby unit, external to treat women with post-natal depression. Groundbreaking research into schizophrenia also took place there.

Sangita Pindoria was taught how to bond with her baby at Shenley

It remained open during a turbulent period in mental health care, when the NHS took over responsibility for asylums, the general public became more interested in psychiatric care, and doctors were making a significant effort to try to tackle what has become one of the biggest problems facing the UK.

Even now, scientists are still trying to find their way in this area.

But Middlesex County Council wanted a place, which according to a 1927 article in the Times, would use the "most modern methods of treatment" and "for a period, at least, be the finest institution of its kind in the world".

From the outset, it was intended to be progressive - patients were housed in villas rather than in corridors leading off a main hospital block, while in 1953, some of the male inmates even helped to build and decorate part of the property as part of a radical treatment called industrial therapy.

Dr Peter Jefferys worked at the hospital as a consultant psychiatrist for 20 years, and was among the last to leave when it closed.

"Of course there was always a stigma about Shenley, it was the case with every county asylum. Children would be warned to watch out, and told the men in white coats would take them away. If you lived in the area, people would steer clear."

But within the medical community, staff made sure they had built a reputation as risk-takers. "It was seen as an advanced hospital at the cutting edge of psychiatric treatment," Dr Jefferys added.

However, not every treatment used at Shenley remains in use in modern mental health care.

Gerald Kirsch, 83, of Harrow, spent most of his life in the hospital being treated for anxiety, agoraphobia and neuroses, and was one of a number of patients who had insulin coma therapy at the hospital - a treatment in vogue during the 1930s and 40s but eventually discredited in the 50s.

Insulin normally tends to be associated with diabetes treatment. It enables cells to take up the amount of glucose they need to provide themselves with enough energy to function properly.

But back then, practitioners believed injecting insulin benefited, external psychiatric patients by helping to remove psychotic thoughts. The high doses would push the patients into a stupor.

The presence of a specially trained nurse was also essential as the treatment - which is also often described as insulin shock therapy - meant patients needed constant monitoring in case of seizures, or in extreme situations, death.

"The night before they would come and collect us and take us to the special room where the therapy took place. We'd be expected to sleep there overnight and be ready to have the injection when we woke up," Mr Kirsch recollected.

"There were about eight or nine of us who would be placed in beds - they were all set out in a line and then the nurses would come round, check we were fine and then inject us with varying levels of insulin so that we would quickly drift off into the deepest sleep imaginable."

Aerial shot of the Shenley Hospital estate taken circa 1987. Patient numbers peaked in 1957 with 2,370 people housed in accommodation built for no more than 2,000.

Gerald Kirsch is one of the few remaining patients who is still able to talk about his memories of Shenley. He learned to speak basic Russian and play the flute, and he worked on the hospital magazine.

Mind in Harrow organised a touring exhibition in 2012, featuring many photos taken by builder John Laing. The John Laing Charitable Trust has donated its collection of images to English Heritage.

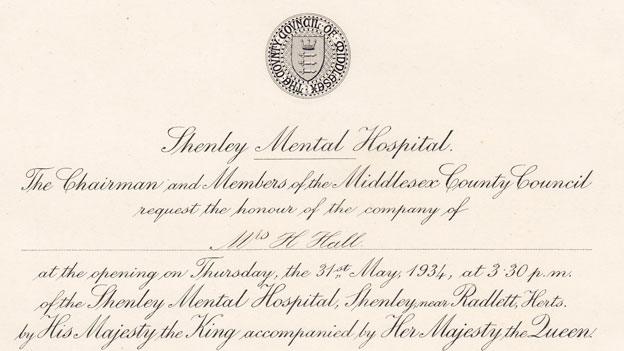

Shenley Hospital was opened by King George V and Queen Mary in 1934 - it had a fully-equipped operating theatre, dental clinics, X-ray rooms, a dispensary, an orchard, garden and farmlands.

After the initial injection, the patients' blood glucose levels would decrease and they could face symptoms such as flushing, sweating and drowsiness before the coma - which could sometimes last for up to an hour at a time - overtook them. The patients would then be woken up through the administration of glucose via nasal tube or intravenously.

"I was luckier than most as I was given a lower dose than some of the others. I had been worried about it but at least at Shenley, they told us what was going on," said Mr Kirsch.

"I didn't like it at all. I'd wake up and feel extremely groggy. We then had to have an escort with us for the rest of the day in case anything happened."

Shenley was also the temporary home of Villa 21, an experiment in anti-psychiatry, external by South African Dr David Cooper. Between 1962 and 1966, several young schizophrenic men and others with similar symptoms, including Mr Kirsch, were under his care.

Dr Cooper tried to break down common institutional boundaries between staff and patients and give patients more control over their own lives and treatment.

The patients were responsible for getting themselves up on time, making sure their ward was clean and looking after their personal hygiene, while those who chose not to take part in occupational therapy sessions were left to do what they wished.

But soon, nobody was cleaning up at all and the ward got filthier. Some patients demanded the staff pay more attention to them and eventually the nursing staff revolted, deciding more structure and intervention was needed.

"While I was there, the patients were allowed to do more or less what they wanted, but I don't think that went down too well with the rest of the hospital. Maybe the doctors running it thought we'd all be capable of making all the decisions, but it just didn't work," Mr Kirsch said.

He did not want to dwell on his short stay there, instead preferring to discuss his psychotherapy and occupational therapy sessions.

But Dr Jefferys said Mr Kirsch's consultant and psychotherapist Dr Tom Hayward had been a key driving force behind Shenley's reputation as a hospital unafraid to take risks.

"Dr Hayward was in charge of the male patients and he was sceptical of the drug treatment of schizophrenics, so Shenley was in a unique position as there would be patients there with those symptoms who had never been given anti-psychotic drugs - sometimes even for decades."

In the 1970s the Medical Research Council set up a research centre at nearby Northwick Park, and Dr Jefferys said this eventually led to a number of "trailblazing research papers into schizophrenia".

For example, CT brain scans of some Shenley patients were among those used to prove that there were actual structural deficits in the brains of those with schizophrenia.

"The researchers were able to access schizophrenic patients who had received years of treatment and indeed those who had not, thus giving them access to fantastic controlled conditions."

Another success story is that of Sangita Pindoria, 45, of Brent.

Diagnosed with post-natal depression, she was admitted as a patient, first to the general ward and then the mother and baby unit, following her son's birth 25 years ago. She credits Shenley with helping her bond with her child.

"I would just be so teary and forgetful all the time. The doctor gave me sleeping tablets and mild anti-depressants but they didn't work."

Her family felt they needed the extra support, especially when she wandered out without her coat during the great storm of 1987 and would accidentally leave the gas on while children were in the house.

While in the general ward, she was separated from her baby - something she found difficult to deal with. Her son was soon allowed to rejoin her in the special unit, although as Mrs Pindoria was medicated overnight, he slept in a separate nursery, watched by a nurse.

"There were 10 of us in the unit, I was lucky to get in as it was so oversubscribed. But it was such a relief to have my baby back with me. They tried to teach us how to get our confidence back and made us take part in lots of activities. We had to look after our own babies - wake them up, sterilise their bottles and bond with them."

When the unit first opened in 1962, the doctors in charge said that mothers who had nervous breakdowns felt even more distressed at being separated from their children.

Shenley was a melting pot of experiences - a place that at one point was at the cutting edge of mental heath care, but then eventually became run down as priorities changed and care in the community became the prevalent train of thought.

Dr Mathew Thomson, a medical historian from Warwick University, said changes at Shenley appeared to reflect the broader changes and processes in similar institutions around the UK.

The attempts Shenley's staff made to ensure they were at the forefront of medical advances meant it was a "wonderful example of how the institutions were not stagnant but were trying to reform and humanise the situation".

But despite all this, the hospital eventually closed its doors, with the final patients leaving in February 1998 to be cared elsewhere. The site was sold for redevelopment.

But for Mrs Pindoria, Shenley is part of her past. "I was sad to leave as it helped me. But I've moved on. I had another son afterwards and am now working and getting on with life."

- Published29 October 2012

- Published8 November 2011

- Published10 October 2011