Warning of three-person IVF 'risks'

- Published

Concerns about the safety of a pioneering therapy that would create babies with DNA from three people have been raised by researchers.

The advanced form of IVF could eliminate debilitating and potentially fatal mitochondrial diseases.

Writing in the journal Science, the group warned that the mix of DNA could lead to damaging side-effects.

The expert panel that reviewed the safety of the technique said the risks described would be "trivial".

The UK is leading the world in the field of "mitochondrial replacement". Draft regulations to allow the procedure on a case-by-case basis will be produced this year and some estimate that therapies could be offered within two years.

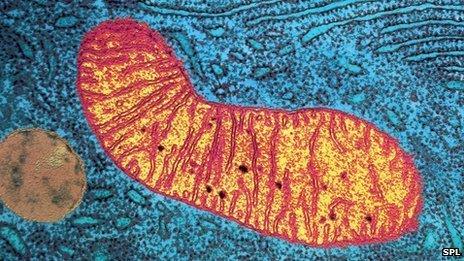

Power source

Mitochondria are the tiny, biological "power stations" that provide nearly every cell, which make up the body, with energy. They are passed from a mother, through the egg, to her child.

But if the mother has defective mitochondria then it leaves the child starved of energy, resulting in muscle weakness, blindness and heart failure. In the most severe cases it is fatal and some families have lost multiple children to the condition.

The proposed therapy aims to replace the defective mitochondria with those from a donor egg.

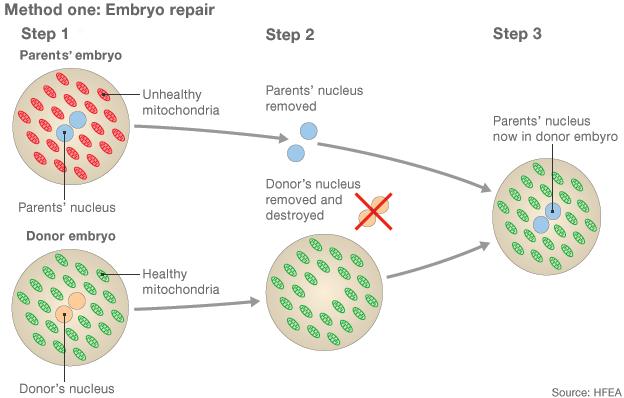

1) Two eggs are fertilised with sperm, creating an embryo from the intended parents and another from the donors 2) The pronuclei, which contain genetic information, are removed from both embryos but only the parents' is kept 3) A healthy embryo is created by adding the parents' pronuclei to the donor embryo, which is finally implanted into the womb

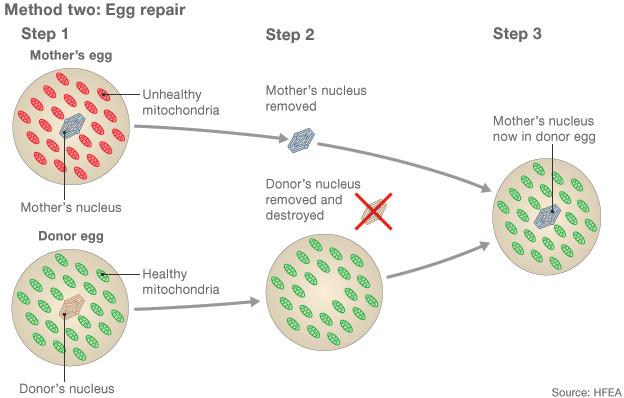

1) Eggs from a mother with damaged mitochondria and a donor with healthy mitochondria are collected 2) The majority of the genetic material is removed from both eggs 3) The mother's genetic material is inserted into the donor egg, which can be fertilised by sperm.

But mitochondria have their own DNA, albeit a tiny fraction of the total. It means a baby would have genetic information from mum, dad and a second woman's mitochondria.

The concerns raised - by scientists at the University of Sheffield, the University of Sussex and Monash University in Australia - are about a poor match between the mitochondrial DNA and that from the parents.

They said there was an interaction between the DNA in the mitochondria and the rest which is packaged in a cell's nucleus.

Their studies on fruit flies suggested that a poor match of genetic information between the nucleus and mitochondria could affect fertility, learning and behaviour.

"Describing it as like changing the batteries in a camera is too simplistic," Dr Klaus Reinhardt from the University of Sheffield told the BBC.

He added : "It is not at all our intention to be a roadblock, we think it is fantastic that for women affected there could be a cure.

"We have pointed out one or two points which need to be looked at."

'Trivial'

The Human Fertilisation and Embryology Authority, which regulates fertility treatment in the UK, commissioned a review into the safety of the technique, external.

Prof Robin Lovell-Badge, who was on the review panel, disagreed. He said humans had diverse mitochondrial and nuclear DNA, so any consequences of poor matches would have already become apparent.

He told the BBC news website: "Humans are breeding between races and producing healthy children all the time. If there is an effect then it must be very trivial as it's not been noticed."

He has called for further safety testing, such as research into the risks posed by any defective mitochondria which might still be passed onto a child.

Prof Doug Turnbull, who is developing the mitochondrial replacement therapy at Newcastle University, insisted: "One of our prime interests is about the safety of these techniques.

"It's perfectly reasonable to draw some of these concerns, I just don't share the same concerns.

"Mismatch between the mitochondrial and nuclear genome is a potential risk, but I don't think it's personally as big a risk as they're saying."

Hundreds of mitochondria in every cell provide energy

The idea has also raised ethical concerns from groups concerned about the impact of altering human genetic inheritance.

In a statement, the Human Fertilisation and Embryology Authority said: "The panel of experts convened by the HFEA to examine the safety and efficacy of mitochondria replacement carefully considered the interaction between nuclear and mitochondrial DNA and concluded that the evidence did not show cause for concern.

"As in every area of medicine, moving from research into clinical practice always involves a degree of uncertainty. Experts should be satisfied that the results of further safety checks are reassuring and long term follow-up studies are crucial.

"Even then patients will need to carefully weigh up the risk and benefits for them."

- Published28 June 2013

- Published12 June 2012

- Published17 September 2012