How much sugar do we eat?

- Published

There is fierce debate about the role of added sugar in contributing to the obesity crisis.

UK government scientists today halved the recommended level of added sugar people should eat each day.

And the World Health Organization has also said people should aim to get just 5% of their daily calories from the sweet stuff.

But calculating how much sugar we eat is not as simple as it sounds.

What are current guidelines?

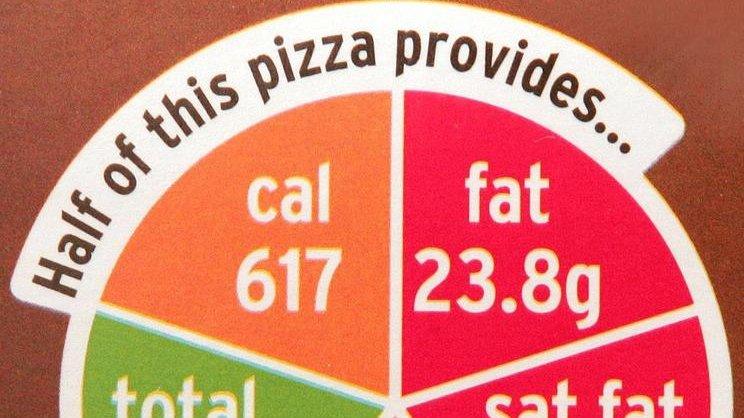

Adding sugar: But it's harder to work out amounts in processed food

Sugar is sugar - right? Not quite. Health professionals take a dim view of sugars added to processed food but say that naturally occurring sweetness in milk and fruit is largely fine, with the exception of juice.

Current advice says no more than 11% of a person's daily food calories should come from added sugars, or 10% once alcohol is taken into account.

That works out at about 50g of sugars for a woman and 70g for a man, depending on how active they are.

And it's this level which has just been halved in a draft report, external by the Scientific Advisory Committee on Nutrition.

But look at the back of a food packet and you'll see a guideline amount for total sugars - including those naturally occurring in fruit and other ingredients.

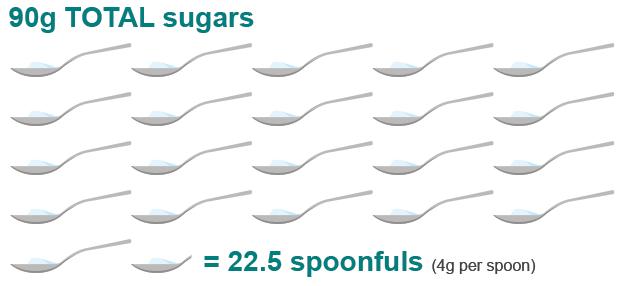

While there is no UK government health guideline for total sugars, the figure of 90g per day is used as a rule of thumb, external on labelling in Britain and across the EU.

That 90g equates to more than 22 small (4g) teaspoons of sugar.

Some sugar content is easy to work out: a 330ml can of regular Coca-Cola or Pepsi contains 35g - or almost nine teaspoons of sugar, all of it added.

But a ready meal of sweet and sour chicken can also contain more than 22g or five-and-a-half teaspoons, some of which is naturally occurring in the pineapple.

And just to confuse things further, packaging previously showed guideline daily amounts (GDA) for men, women and children but this has been replaced by reference intakes (RI), external - which, under European legislation, can only be shown for adults.

Reference intakes are not the same as dietary reference values (DRVs), which are what health professionals use when calculating added sugars - taking us back to the 10-11%.

"It's nigh on impossible for people to work out how much added sugars they are consuming," says nutritionist Katharine Jenner, of campaign group Action on Sugar.

How much sugar are we taking in?

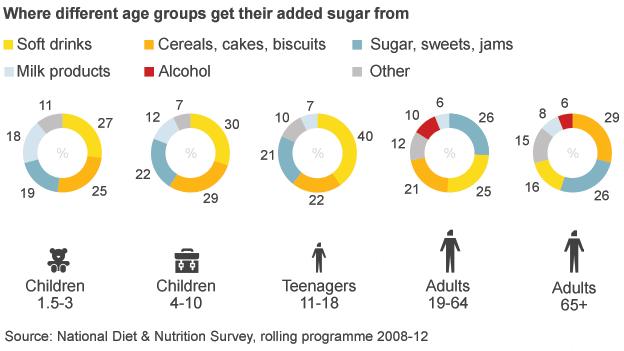

Teenagers get 40% of their daily added sugar from soft drinks

All methods of assessing a population's food intake have their limitations. Anyone who has tried to keep a food diary knows how difficult it is to remember every morsel consumed: from office biscuits to the kids' leftovers.

However, the National Diet and Nutrition Survey is the most complete probing of the UK's eating habits.

The latest NDNS report found that all age groups were eating more added sugar (technically known as non-milk extrinsic sugars) than the 11% level but that children were exceeding it to the greatest degree.

Young people aged 11-18 get the most of their daily energy from sweet stuff at more than 15%. Adults are more measured, just nudging over 11%.

Where do we get it from?

Soft drinks are the biggest single source of added sugar for young people, with boys aged 11-18 getting 42% of their intake this way.

Sweets, chocolate and jams made up another 19-22% of children's sugar intake and younger children also get a large proportion of their sugar from cereals - including cakes and biscuits - and drinks including fruit juice.

For adults aged 19-64, the main sources are also confectionery and jams, soft drinks and cereals. Alcohol adds another 10%.

Health effects

Scientists are still investigating whether there are direct causal links between high sugar intake and weight gain, type 2 diabetes, heart disease and other illnesses.

What is known is that eating too many calories without enough exercise can lead to obesity - and obesity is a risk factor for other conditions.

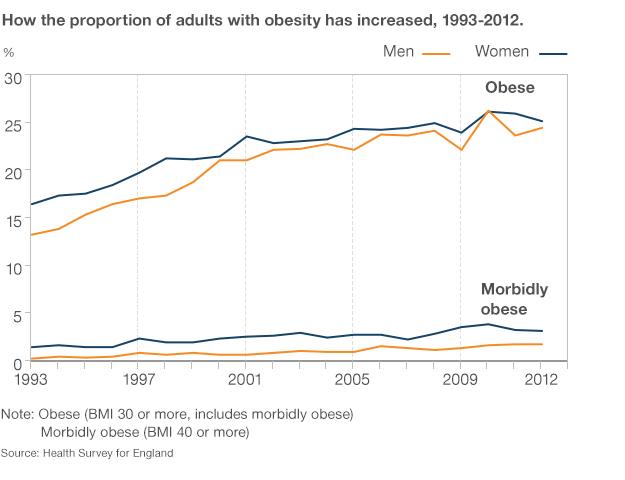

Latest figures show obesity in England climbing over recent decades before levelling off.

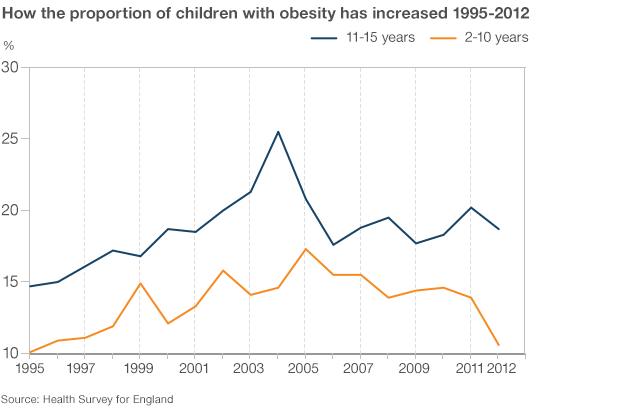

Among young children, the proportion who are obese has fallen but campaigners say more still needs to be done to reduce the amount of sugar children eat.

- Published26 June 2014

- Published27 June 2014

- Published26 June 2014

- Published1 April 2014

- Published1 April 2014

- Published5 March 2014

- Published19 June 2013

- Published11 July 2012

- Published7 July 2011