HIV evolving 'into milder form'

- Published

HIV is evolving to become less deadly and less infectious, according to a major scientific study.

The team at the University of Oxford shows the virus is being "watered down" as it adapts to our immune systems.

It said it was taking longer for HIV infection to cause Aids and that the changes in the virus may help efforts to contain the pandemic.

Some virologists suggest the virus may eventually become "almost harmless" as it continues to evolve.

More than 35 million people around the world are infected with HIV and inside their bodies a devastating battle takes place between the immune system and the virus.

HIV is a master of disguise. It rapidly and effortlessly mutates to evade and adapt to the immune system.

.jpg)

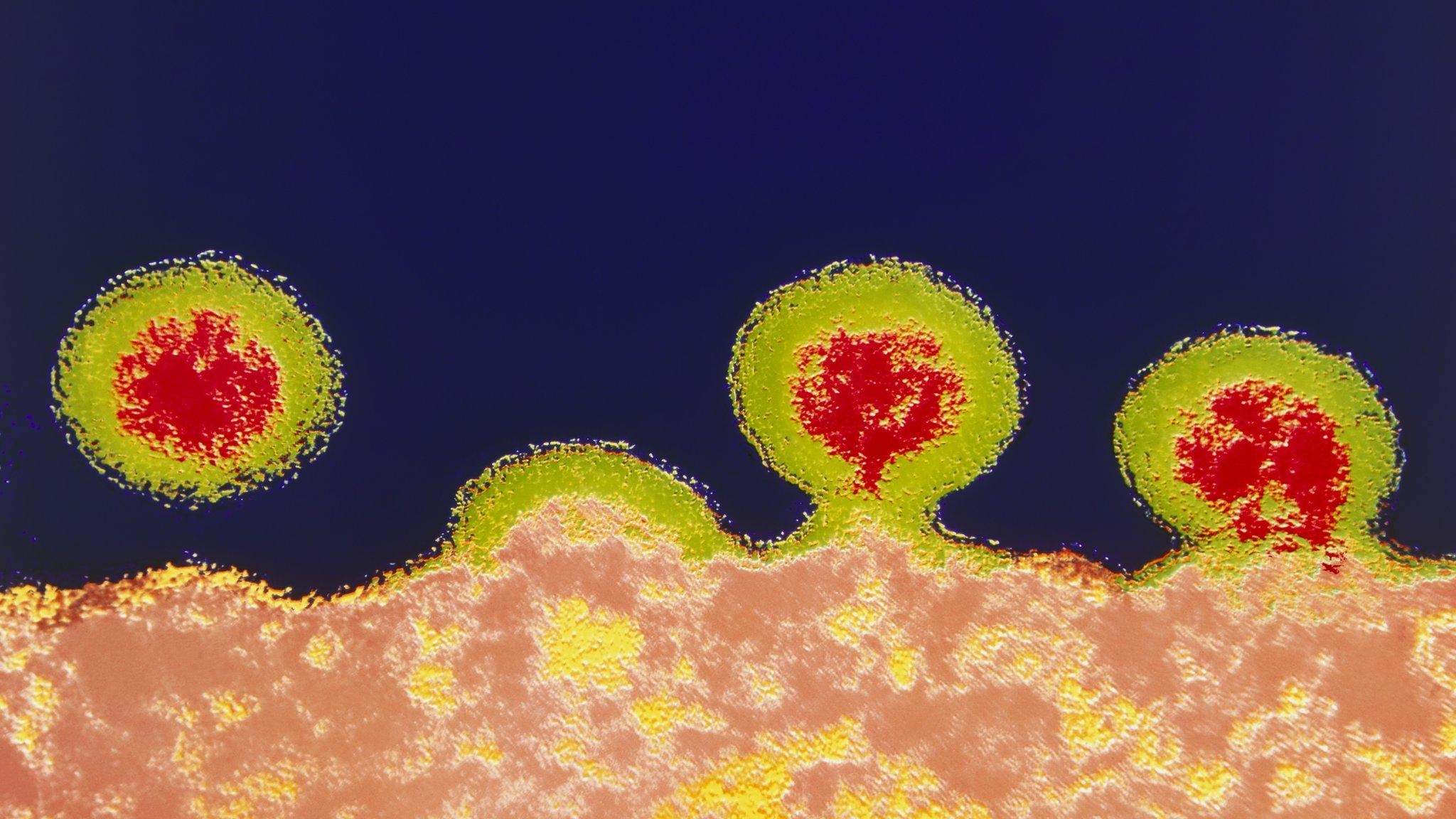

HIV, in red, has infected a cell in the immune system, yellow.

However, every so often HIV infects someone with a particularly effective immune system.

"[Then] the virus is trapped between a rock and hard place, it can get flattened or make a change to survive and if it has to change then it will come with a cost," said Prof Philip Goulder, from the University of Oxford.

Weakened

The "cost" is a reduced ability to replicate, which in turn makes the virus less infectious and means it takes longer to cause Aids.

Prof Dausey, Mercyhurst University: "We have to be cautiously optimistic about this study"

This weakened virus is then spread to other people and a slow cycle of "watering-down" HIV begins.

The team showed this process happening in Africa by comparing Botswana, which has had an HIV problem for a long time, and South Africa where HIV arrived a decade later.

Prof Goulder told the BBC News website: "It is quite striking. You can see the ability to replicate is 10% lower in Botswana than South Africa and that's quite exciting.

"We are observing evolution happening in front of us and it is surprising how quickly the process is happening.

"The virus is slowing down in its ability to cause disease and that will help contribute to elimination."

Drug bonus

The findings in Proceedings of the National Academy of Sciences, external also suggested anti-retroviral drugs were forcing HIV to evolve into milder forms.

It showed the drugs would primarily target the nastiest versions of HIV and encourage the milder ones to thrive.

Prof Goulder added: "Twenty years ago the time to Aids was 10 years, but in the last 10 years in Botswana that might have increased to 12.5 years, a sort of incremental change, but in the big picture that is a rapid change.

"One might imagine as time extends this could stretch further and further and in the future people being asymptomatic for decades."

The group did caution that even a watered-down version of HIV was still dangerous and could cause Aids.

HIV originally came from apes or monkeys, in which it is frequently a minor infection.

Prof Jonathan Ball, a virologist at the University of Nottingham, told the BBC: "If the trend continues then we might see the global picture change - a longer disease causing much less transmission.

"In theory, if we were to let HIV run its course then we would see a human population emerge that was more resistant to the virus than we collectively are today - HIV infection would eventually become almost harmless.

"Such events have probably happened throughout history, but we are talking very large timescales."

Prof Andrew Freedman, a reader in infectious diseases at Cardiff University, said this was an "intriguing study".

He said: "By comparing the epidemic in Botswana with that which occurred somewhat later in South Africa, the researchers were able to demonstrate that the effect of this evolution is for the virus to become less virulent, or weaker, over time.

"The widespread use of antiretroviral therapy may also have a similar effect and together, these effects may contribute to the ultimate control of the HIV epidemic."

But he cautioned HIV was "an awfully long way" from becoming harmless and "other events will supersede that including wider access to treatment and eventually the development of a cure".

- Published1 December 2014

- Published1 December 2014

- Published3 October 2014

- Published16 July 2014

- Published30 November 2011

- Published10 July 2014

- Published22 July 2014

- Published3 October 2014

.jpg)

- Published21 July 2014