Mitochondrial disease study raises hope of treatment

- Published

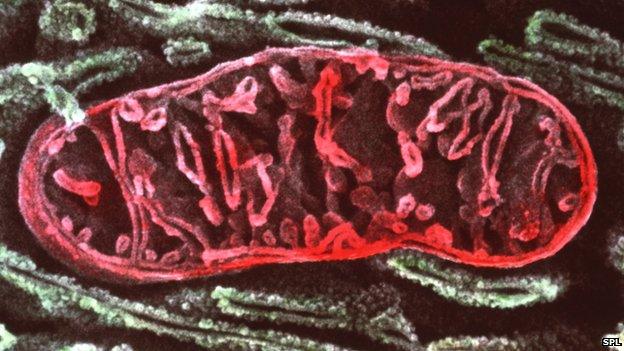

Mitochondria are tiny structures that convert food into useable energy for the body

US scientists say they have taken the first step towards treating people born with mitochondrial diseases - debilitating genetic disorders.

Their study, in Nature, external, showed healthy cells could be produced in the laboratory from affected patients.

The team suggest future treatments could use the healthy tissues to repair the heart and other damaged organs.

Experts said the study was exciting and "beautifully executed" but cautioned there was still far more work ahead.

One in every 6,500 babies has severe mitochondrial disease, leaving them lacking energy and resulting in muscle weakness, blindness, heart failure and even death.

Mitochondria are the tiny compartments inside nearly every cell of the body that convert food into usable energy.

Defective mitochondria are passed down only from the mother, and this year the UK made a landmark decision to allow the creation of "three-person babies" to prevent children being born with the fatal disease.

However, the measure would not help anybody who currently has the condition.

Cloned sheep

The team at the Oregon Health and Science University used two techniques to produce healthy tissue samples from affected patients.

The first relied on the fact that out of the hundreds of mitochondria in every cell, there is a mixture of healthy and defective ones.

By taking and growing multiple samples of skin cells, the researchers could find a range of cells with between 0% and 100% healthy mitochondria.

The second method involved the same technique used to produce the first cloned animal - Dolly the sheep.

The core genetic information, the nucleus, was placed inside a healthy woman's egg and then electricity was used to encourage the egg to develop into a healthy embryo.

Both methods produced stem cells - a type of cell that can be transformed into any other type - which hold huge promise in medicine.

'Cure on the horizon'

One of the researchers, Prof Shoukhrat Mitalipov, told the BBC News website: "There is a long way to go - it's the same issue as in regenerative medicine.

"There has been considerable research into turning stem cells into the desired tissue type.

"Then the next step is to harvest and transplant them into a patient, to ensure they implant, integrate and function well."

This is the great challenge, but Prof Mitalipov says: "Today we can say that a cure is on the horizon."

Prof Robin Lovell-Badge, from the Francis Crick Institute, said the research was "interesting and important".

However, he warned there were challenges ahead in harnessing this approach as a treatment. "The problem here will be to devise methods to replace cells within the patient.

"This might be feasible for muscle, where there are stem cells that are responsible for cell turnover within the tissue, but it will be very difficult for heart and brain cells, where cell turnover is very low or non-existent."

Prof Darren Griffin, from the University of Kent, said: "This is clearly a very exciting study that might pave the way to possible treatment of mitochondrial disorders.

"It will, however, be some time before it can be applied clinically."

- Published15 May 2013

- Published24 February 2015

- Published3 February 2015

- Published1 February 2015

- Published30 January 2015

- Published3 February 2015

- Published1 September 2014

- Published27 February 2014

- Published3 June 2014

- Published28 June 2013