Antibiotics: Are we reckless drivers when it comes to drugs?

- Published

Imagine someone who went through dozens of cars after repeatedly crashing them. Would you buy them a new one?

I'm sure everyone is sensibly thinking no, but that is the exact approach we have all adopted for antibiotics, the miracle drugs that have transformed medicine and kill bacteria.

But bacteria themselves are wily and rapidly learn new ways of surviving, which render the drugs powerless.

When one drug stops working we just move onto another (and another and another, you get the idea).

This has been exacerbated by overusing antibiotics to such an extent that people are now talking about an "antibiotic apocalypse" in which none of the drugs work.

One response has been to reinvigorate research that has failed to find a new class of antibiotic since the 1980s, external.

A review by the economist Jim O'Neill called for a $2bn (£1.3bn) "innovation fund" and guaranteed payments for companies that produced new antibiotics.

But if we did produce new drugs, without changing the way we use them, then all we could do is delay the "apocalypse".

Returning to our careless driver - do we really need to be talking about driving lessons rather than new cars?

Bacteria can spread resistance rapidly

"I think we are a significant way from using antibiotics responsibly. Some healthcare systems are making huge progress and I would put the UK at the front of that, but if I took a global view then we really are a significant way away," said Prof Dilip Nathwani, the president of the British Society for Antimicrobial Chemotherapy and an adviser to the Scottish government.

In the UK the dangers of antibiotic resistance are even acknowledged right at the top of government.

Prime Minister David Cameron has warned: "We are looking at an almost unthinkable scenario where antibiotics no longer work and we are cast back into the dark ages of medicine where treatable infections and injuries will kill once again."

But despite this awareness of the dangers of antibiotic overuse, figures suggest that around 10 million antibiotic prescriptions - out of the total of 42 million given out each year - are inappropriate.

Patients have been criticised for an "addiction" to the drugs and doctors have been accused of being a "soft-touch" either too keen to prescribe them or rapidly wilting under patient demand.

It means patients are taking antibiotics for conditions that would resolve themselves or for which they would never work - such as viral infections causing colds and sore throats.

Prof Nathwani added: "My grandmother who passed away last year was brought up in India. She would tell of siblings and friends who died of infections, our public really need to think 'is that what they would like?'.

"They will see rampaging multi-drug resistant infections that cause deaths like they did in the old days."

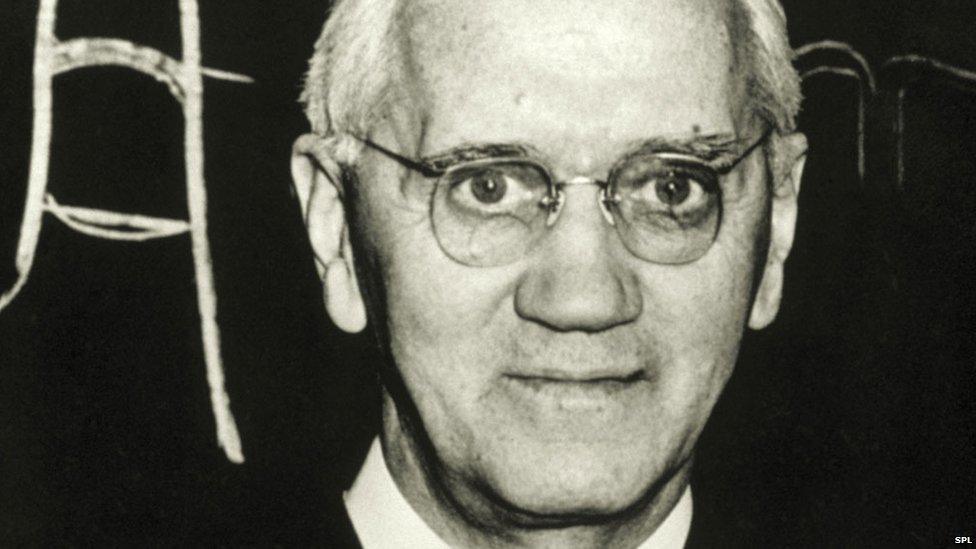

Sir Alexander Fleming discovered antibiotics when he noticed that mould growing on his culture dishes had created a ring free of bacteria

And that is the talk in a country that is actively trying to curb antibiotic use.

Many countries do not even require a prescription or doctors appointment for antibiotics as they are available simply over the counter.

It means the medication is taken without medical advice and as the man who discovered antibiotics, Sir Alexander Fleming, said in 1945 it risks fuelling resistance.

He used his Nobel Prize-winning speech to say: "It is not difficult to make microbes resistant to penicillin in the laboratory by exposing them to concentrations not sufficient to kill them, and the same thing has occasionally happened in the body.

"The time may come when penicillin can be bought by anyone in the shops.

"Then there is the danger that the ignorant man may easily under dose himself and by exposing his microbes to non-lethal quantities of the drug, make them resistant."

And there are not just problems in the way we treat ourselves. The misuse of antibiotics in pets, livestock and fish farms all serve to exacerbate the problem.

There are some promising signs that new drugs are on the horizon.

This year a group in the US reported a new method of growing bacteria in "subterranean hotels" which has yielded 25 new potential antibiotics, with one deemed "very promising".

But there is still a long way to go before we know how to use them responsibly.

- Published19 November 2015

- Published10 October 2014

- Published14 May 2015

- Published6 April 2015