Facebook Q&A: Tulip Mazumdar answers your questions on the Zika vaccine

- Published

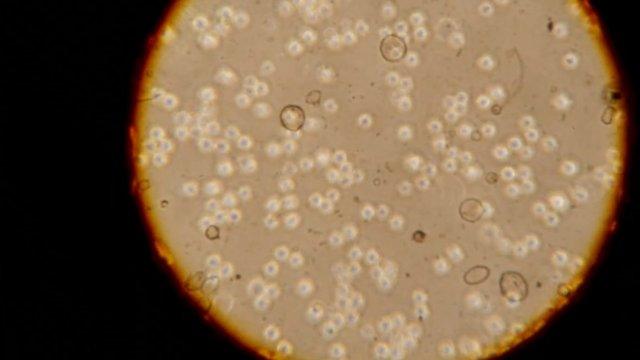

The Zika virus is spread by the Aedes aegypti mosquito, which also carries dengue fever and yellow fever

The BBC's Global Health Correspondent Tulip Mazumdar has been investigating a new Zika vaccine which could be ready for human trials later this year.

Tulip has been covering the outbreak over the past few months, reporting on the children born with microcephaly and other birth defects believed to be caused by the virus as well as speaking to scientists who are leading the fight back against Zika.

Many of you got in touch on Facebook to ask Tulip questions about the new vaccine, and when it might be available to pregnant women.

This is an edited version of the Facebook Q&A, external.

Question from Dawn McLean, external: Have you tested the vaccine already? How do you know if it works or not?

Tulip answers: Human trials haven't started for the vaccine being developed by the National Institutes of Health - where I have been reporting from this week. They are due to start - assuming no major problems - in the summer/ autumn of this year.

If the vaccine is found to be safe with no concerning side effects, the drug will be given to a larger number of people to test how effective it is and further evaluate its safety. The final phase is giving it to large groups of people to confirm how effective it is.

Question from Priscilla Wakanuma: How possible is it to make a vaccine for this virus?

Tulip replies: Scientists here in Bethesda at the National Institutes of Health think it's very possible. They already have a vaccine for a similar virus - West Nile - which they have been working on.

So they're using some of the tried and tested methods from that to try and develop a vaccine for Zika ASAP.

The World Health Organisation says that a link between the Zika Virus and a rise in the number of babies born in South America with microcephaly and other birth defects is "strongly suspected".

Taj Rahman, external asks: The vaccine is available in November, I thought this was a global emergency?

Tulip replies: Hi Taj - getting vaccines ready for market takes years, often decades. They have to go through stringent safety and efficacy trials and then get signed off by a whole load of regulatory bodies.

When the WHO declared this public health emergency last month, one of the key things they highlighted was the urgent need for research into new vaccines. Scientists and pharmaceuticals came together very fast on Ebola, it's hoped that can happen again this time.

But sadly, many more babies are expected to be born with these birth defects in the meantime.

Question from Hannah Borrett, external: How have they managed to push through the development so quickly?

Tulip replies: You're right, it can take years, decades even to get a new vaccine through all the clinical trials and then signed off through all the various national and international regulatory authorities. But in an emergency - which the Zika outbreak now is - things can be fast-tracked.

A lot more money is put into research, and there's a much bigger political will to get things moving fast.

Take the Ebola outbreak for example, there are now a couple of candidate vaccines that could be used in an outbreak that have shown some efficacy. Research - and cash - for that vaccine was pushed through super quickly.

Adebola Misturah Martins-Bello asks about plans to prioritise who will be considered a priority for the vaccine.

Tulip replies: The plan here at the National Institutes of Health is to have a special focus on protecting pregnant women.

The virus isn't particularly harmful for most people, but the concern is this strongly suspected link to babies of infected mothers being born with under developed brains.

If a link if confirmed, and a vaccine is developed quickly - health authorities will look into whether to add it to childhood vaccines, a bit like the rubella vaccine, which also protects girls/ women if they have babies later in life.

You can follow @tulipmazumdar , externalon Twitter.

- Published4 March 2016