What's it like living with a face transplant?

- Published

Ms Dinoire in 2006 after her operation

She underwent the world's first face transplant in 2005 and later said her donor had "saved her life" - but the transplant may also have shortened it.

Isabelle Dinoire died in April aged 49 of cancers that spread all the more quickly because of treatment to prevent her body rejecting her new face.

She had the transplant after being left disfigured by her pet labrador, which gnawed off her nose and lips while trying to revive her after a suicide attempt.

Nadey Hakim, who helped treat Ms Dinoire, says she would have been aware of the risk.

"It's a known fact that whoever is transplanted is more likely to be prone to cancer, not in the organ that has been transplanted but any cancer," said Mr Hakim, now professor of transplant surgery at Imperial College London.

"If you are on immunosuppressants, you are not going to fight cancer the same way. It will spread and multiply much quicker than if you have the policeman around to stop it."

Feeling 'normal' again

About 40 face transplants have been carried out since Ms Dinoire's pioneering procedure.

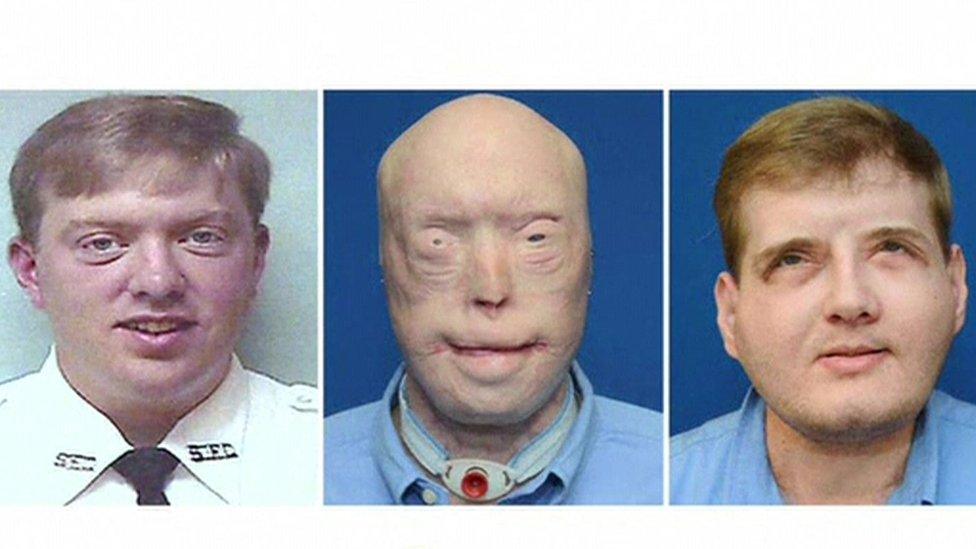

Some, such as the world's most extensive face transplant carried out on a volunteer firefighter in the US, appear to have been a stunning success.

Patrick Hardison: "I'd like to say I'm the same old Pat, but that would not give enough credit to the amazing journey I've been though"

Patrick Hardison, whose surgery was the first to include scalp and functioning eyelids, said in August that he felt like a "normal guy" for the first time in 15 years.

He had 71 reconstructive surgeries before the transplant after a burning building fell on him in 2001.

"Before the transplant, every day I had to wake up and get myself motivated to face the world," Mr Hardison said.

"Now I don't worry about people pointing and staring or kids running away crying. I'm happy."

For Ms Dinoire, the pointing and staring came after the transplant.

In 2006, Isabelle Dinoire described the moment she saw her disfigured face

"It was excruciating. I live in a small town and so everyone knew my story. It wasn't easy at the beginning.

"Children would laugh at me and everyone would say, 'Look it's her, it's her'," she told the BBC in 2012.

Rejected by the body

A new face can, however, be easier to accept than a different body part, Prof Hakim says.

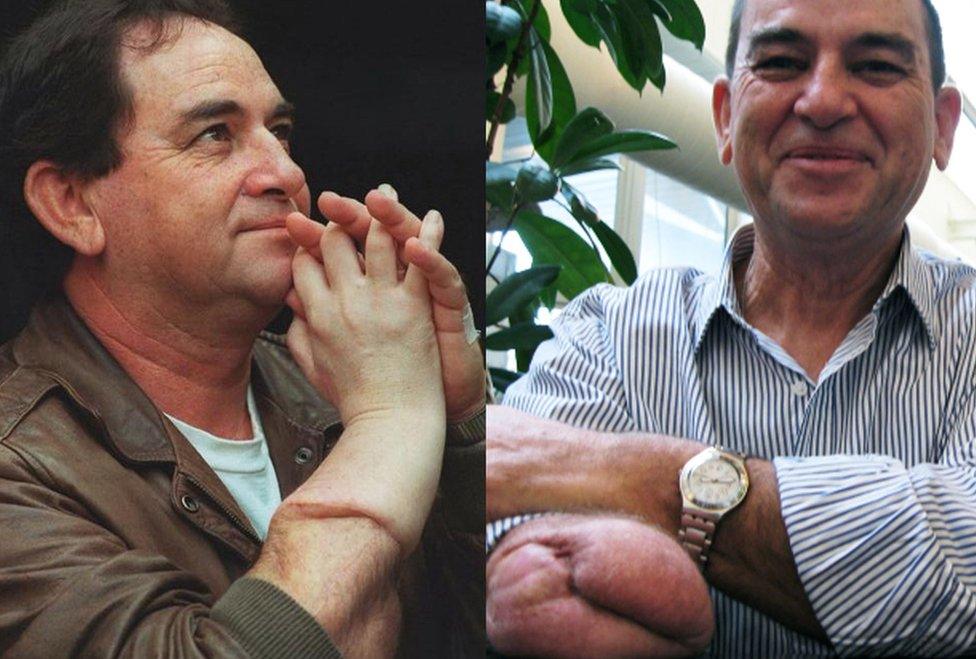

He eventually severed the donor hand he himself had transplanted in a world-first onto New Zealander Clint Hallam in 1998 after Mr Hallam stopped taking immunosuppressants because he could not afford them.

"Living with a transplant is not easy. You have the arm of someone else, it's a dead person's hand you are carrying. At one point he himself started hating it," Prof Hakim said.

Without the immunosuppressants, his body began rejecting the new hand.

Clint Hallam had the first hand transplant but it was later removed after his body rejected it

"The hand started disintegrating, it went red and then white, it looked horrible," said Prof Hakim.

"It can only be better with the face. People have such deformities, bad enough to wear a mask or not go out at all."

Managing expectations

In some cases however, a transplant may not be the best option, says Dr James Partridge from the organisation Changing Faces, external.

He founded the organisation in 1992 after suffering severe burns in a car fire aged 18. It campaigns for equal treatment for people who, for reasons such as injury, illness, paralysis or congenital condition, have unusual faces.

Dr Partridge says the quality of information about the medical treatment on offer is "absolutely crucial".

Changing Faces founder Dr Partridge suffered burns to his face in a car accident

Those like the "very courageous" Ms Dinoire, who was advised that a transplant was the only option, have not only a higher cancer risk but also the possibility their hopes for the procedure might not be met, he says.

"We can't deny that surgery has aesthetic limits and most people who contact us are in the position of having to accept that, like it or not, there's a limit to how much aesthetic change they can get," he said.

"That was my case - what I call the diminishing returns of surgery - which meant I had to psychosocially adjust to what I was going through. And this has not been given anything like as much attention as it should be."

The interventions Changing Faces has created are now being incorporated by some surgeons into patient care programmes, he says.

They include learning new social skills to manage other people's reactions and developing a positive attitude.

"Surgery has limits - you need the psychosocial to back it up. Dammit you are going to feel sad and lonely," said Dr Partridge.

Mr Hardison, seen in August, said seeing his children again was among his happiest moments

Both Ms Dinoire and Mr Hardison pondered their identity after their respective face transplants.

For Ms Dinoire there was a sense of loss, but also of companionship.

"When I look in the mirror, I see a mixture of the two [of us]. The donor is always with me," she said in 2012.

Mr Hardison struck an upbeat note.

"I'd like to say that I'm the same old Pat, but that would not give enough credit to the amazing journey I have gone through this past year," he said last month.

"The road to recovery has been long and hard, but if I had to do it again, I'd do it in a heartbeat."

- Published6 September 2016

- Published24 August 2016

- Published24 November 2015

- Published17 November 2015

- Published27 November 2012