Can sweat patches revolutionise diabetes?

- Published

Scientists have developed a sensor that can monitor blood sugar levels by analysing sweaty skin.

But rather than a gym-soaked t-shirt, it needs just one millionth of a litre of sweat to do the testing.

The team - in South Korea - showed the sensor was accurate and think it could eventually help patients with diabetes.

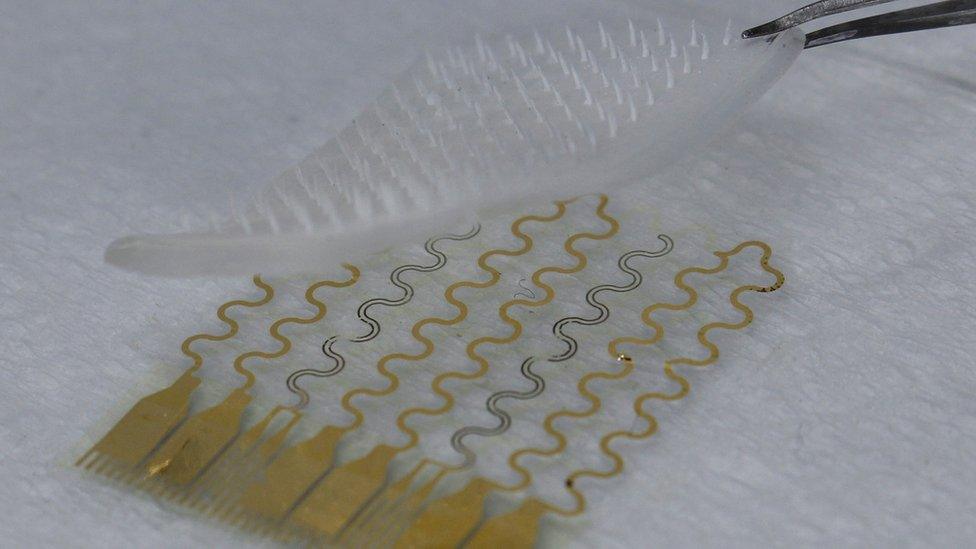

And in extra tests on mice, the sensor was hooked up to a patch of tiny needles to automatically inject diabetes medication.

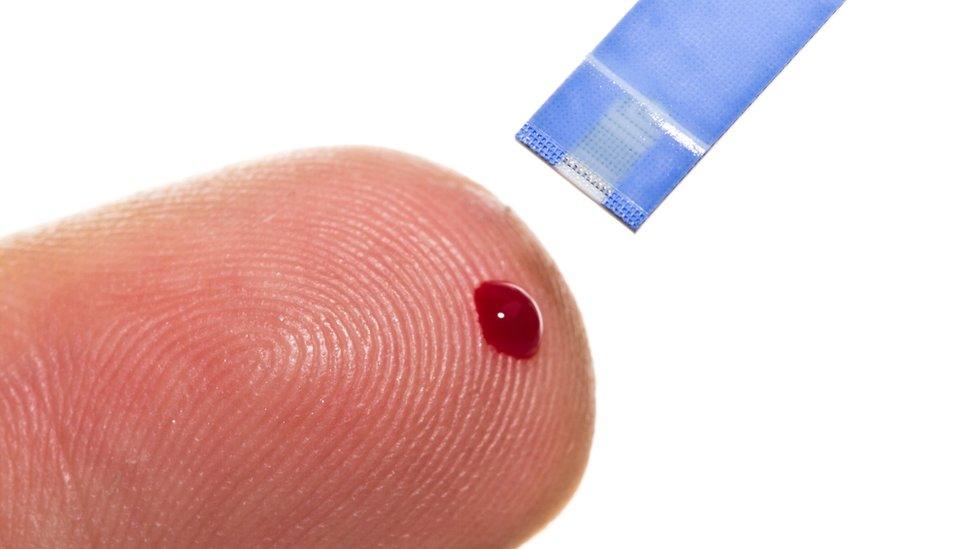

The team at the Seoul National University were trying to overcome the need for "painful blood collection" needed in diabetes patients.

Type 1 diabetes is caused by the immune system attacking the part of the body that controls blood sugar levels

Type 2 diabetes is often caused by lifestyle damaging the body's ability to control blood sugar levels

Patients with both conditions need to medically control their blood sugar levels to prevent damage to the body and even death

This is how patients with diabetes would normally keep track of blood sugar levels:

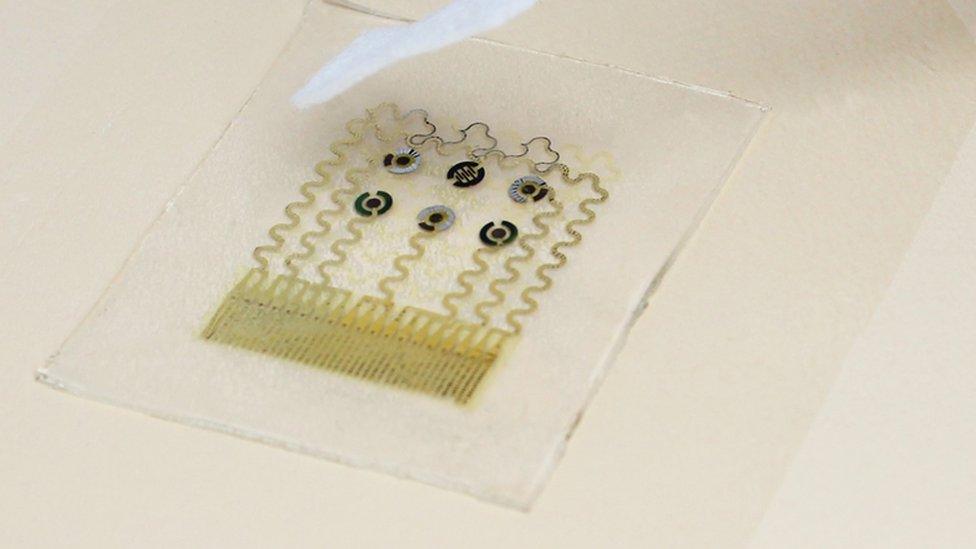

And this could be the future:

The sensor is flexible so it can move with the skin it is stuck onto.

However, the scientists needed to overcome a series of challenges to make it work.

There is less sugar in sweat than blood so it is harder to find, and other chemicals in sweat such as lactic acid can disrupt the results.

So the patch has three sensors keeping track of sugar levels, four that test the acidity of the sweat and a humidity sensor to analyse the amount of sweat.

It is all encased in a porous layer that allows the sweat to soak through and bathe the electronics.

All this information is passed onto a portable computer which does the analysis to work out the sugar levels.

Tests before and after people sat down for a meal, published in the journal Science Advances, external, showed the results from the sweat patch "agree well" with those from traditional kit.

However, for the next stage the researchers turned to mice with diabetes.

They used the blood sugar monitor to control an array of microneedles to give the mice doses of the diabetes drug metformin.

The researchers conclude: "The current system provides important new advances toward the painless and stress-free" care for diabetes.

However, there is a leap between proving something can sense sugar levels in a lab and turning that into something that is so reliable people can put their lives in its hands.

So the researchers next want to test how the patches work in the long-term.

Follow James on Twitter, external.