Jeremy Hunt: The longest-serving health secretary

- Published

He has overseen worsening waiting times for cancer care, hospital operations and emergency treatment. Hospitals have bust their budgets by record amounts. And there has been the first all-out strike by doctors. But despite all this, Jeremy Hunt has remained as health secretary in England.

With five years and 274 days under his belt, he is the longest-serving custodian of the NHS, having surpassed Margaret Thatcher's Health Minister, Norman Fowler, and Aneurin Bevan, the man who set up the health service in the first place. How has he survived so long?

The holiday that shaped Hunt

To understand Mr Hunt's reign, you need to go back to the start. He was appointed, in September 2012, because he was seen as a skilled communicator who could help articulate a clear vision for the health service after the furore over the changes implemented by his predecessor, Andrew Lansley.

Mr Hunt immediately took a different tack - and it is one that has come to shape his time as health secretary. One of his first moves as health secretary was to go on holiday with his family. It had already been booked, following the London Olympics and a tricky period as culture secretary during which he had become embroiled in row over his relationship with Rupert Murdoch's News Corp.

He had a controversial time as culture secretary

While on holiday, he read the report into the Stafford Hospital scandal, which Sir Robert Francis had just finished. Those close to him said the findings had horrified him. It was not just the poor care and suffering that had happened, but that it had been allowed to go on so long without the alarm being raised.

He came back convinced he needed to champion patient safety. In the following years, he went on to overhaul the inspection regime, introduce a new duty of candour on staff and fresh rules about whistle-blowers.

Someone working with him at the time told me this was "classic Jeremy". They said: "He likes to pick a central theme and focus on it relentlessly. It is how he believes you get things done in government."

A game-changer on patient safety?

In the speeches I've heard over the years, he runs through the stories of those who have suffered.

People such as:

Julie Bailey, whose mother was treated at Stafford Hospital

James Titcombe, whose son died at Cumbria's Furness General Hospital at nine days old after staff missed opportunities to save him

Melissa Mead, whose one-year-old son, William, died from sepsis that was not picked up by health staff the family had contact with

Joshua Titcombe was nine days old when he died

It is powerful stuff. These are the very worst examples of NHS care. They should never have happened. And only his harshest critics would disagree with what he says about them.

Mr Titcombe has said the health secretary's efforts should be applauded. He believes he has "changed the game when it comes to patient safety".

"I watched my son die. And then I watched the NHS close ranks afterwards," Mr Titcombe said. "[Mr Hunt] was [one of] the few people who listened. And he took action."

Is Hunt toxic to staff?

But what has annoyed many who work in the NHS is the way he has gone about tackling the problem. They feel he has blamed them and questioned their professionalism at a time when his government has overseen the toughest funding settlement the NHS has ever had.

Nowhere is this clearer than in his handling of the junior-doctor contract row. Emboldened by the election victory in 2015, Mr Hunt returned to office determined to achieve the manifesto commitment of creating a seven-day NHS and - as a result, he argued - safer care for patients.

He was markedly more aggressive than he had been in his first two and a half years in post. He criticised what he said was a "Monday to Friday" culture, prompting an outpouring of anger. On social media, medics started posing photographs of themselves at work using the hashtag #ImInWorkJeremy.

The clash set the tone for a difficult few months for the health secretary. Contract negotiations with junior doctors had already started and stalled. And the stalemate soon worsened, with the British Medical Association balloting for industrial action. After months of wrangling, junior doctors took part in a series of walkouts, two of which involved all-out strikes where emergency care was not covered - the first time that had ever happened in the NHS.

Mr Hunt acknowledges this was his most difficult time as health secretary. And while he remains unapologetic for taking on the BMA, which he says was spreading misinformation about the contract, he accepts he should have done more to tackle one major complaint of doctors - rota gaps.

Since the dispute, he has announced increases in training places for both doctors and nurses.

Was he fired?

Following the strikes, Mr Hunt's approval rating actually dropped lower than predecessor Andrew Lansley's had at the height of his troubles.

And by the time Theresa May became prime minister, in the summer of 2016, there was strong speculation that he was going to lose his job.

In fact, on the morning of her first reshuffle, there were reports he had actually been sacked but then reinstated when it had become clear not all the people Ms May had earmarked for posts in her first cabinet had been willing to take up the offer.

This has been denied by Mr Hunt and his team - and certainly the health secretary had the last laugh by tweeting on the day: "Reports of my death have been greatly exaggerated."

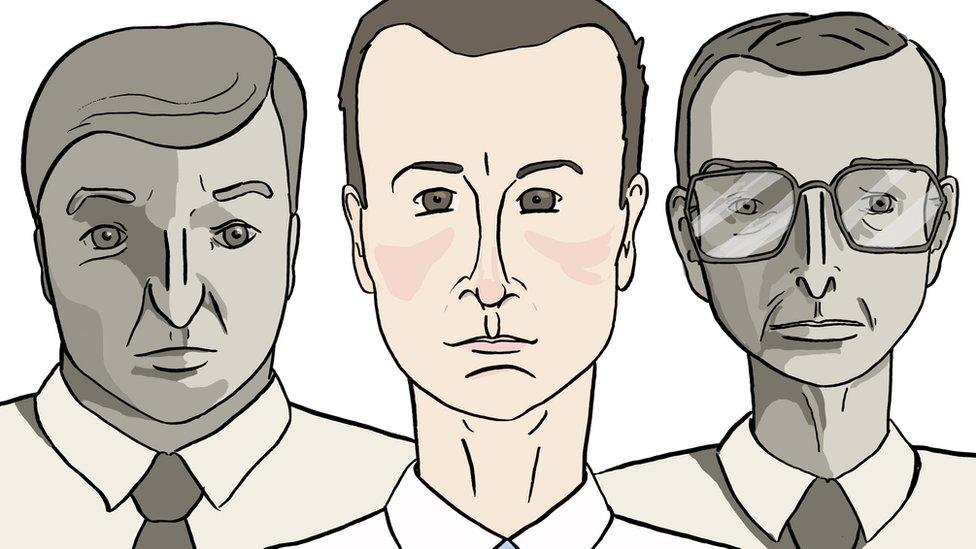

The five longest-serving health ministers

The three longest-serving health ministers - Nye Bevan (left), Jeremy Hunt (centre) and Norman Fowler (right)

Jeremy Hunt (Conservative) - five years and nine months (September 2012 - present)

Norman Fowler (Conservative) - five years and nine months (September 1981 - June 1987)

Aneurin Bevan (Labour) - five years and five months (August 1945 - January 1951)

Kenneth Robinson (Labour) - four years (October 1964 - November 1968)

Sir Keith Joseph (Conservative) - three years and eight months (June 1970 - March 1974)

The mere fact he has survived so long in one of the most demanding posts in government means speculation about his future is a given. Ahead of the last election, reports surfaced that Ben Gummer, who has served as a junior minister under Mr Hunt, had been earmarked as the next health secretary.

But Mr Gummer lost his seat. And, with Theresa May left weakened following the election, there was limited change in the cabinet. Indeed, some began to see Mr Hunt's longevity as a benefit to the government during a period when NHS waiting times have worsened and attracted negative headlines.

Norman Lamb, a former Liberal Democrat health spokesman and a minister in the coalition, once described him as the "shock absorber", able to take the flak for the government.

But as he has gone on and with the NHS in its 70th year, there is a sense attitudes towards Mr Hunt have begun to change again.

At the last reshuffle, in the winter, it is understood he was offered the job of business secretary but this time had the confidence to tell the prime minister he wanted to stay where he was.

Even among his critics, this news was met with a grudging acceptance. There is, it seems, a growing feeling - even among those who have wished him out in the past - that it is better to have someone in post who understands the health service and has the power to argue for it at the cabinet table than a newcomer.

Behind the scenes, Mr Hunt was championing the need for a long-term funding settlement in late 2017 - and the fact that the prime minister has now committed to that is in large part down to his influence.

Discussions about how big a rise the NHS should receive continue. But by all accounts Mr Hunt is pushing back against the Treasury, which seems to want to offer only an extra 2% a year when economists are arguing it will need to be nearer 4% if the NHS is to remain in good health.

How he fares in those discussions could well shape his legacy as health secretary.

- Published8 February 2017

- Published8 February 2017

- Published6 January 2017

- Published12 December 2016

- Published13 September 2016