'Kinder treatments in pipeline' for child brain cancer

- Published

Researchers have found there are seven types of the most common malignant child brain cancer - paving the way for more precise, "kinder" treatments.

Medulloblastoma affects about 70 to 80 children a year in the UK and requires intensive treatment including surgery, chemotherapy and radiotherapy.

That can leave children with life-altering injuries.

But the breakthrough means targeted treatments could be developed and some of the side-effects avoided.

The finding, reported in Lancet Oncology, external, has been welcomed by families affected by the condition, which is responsible for a fifth of all child brain cancers.

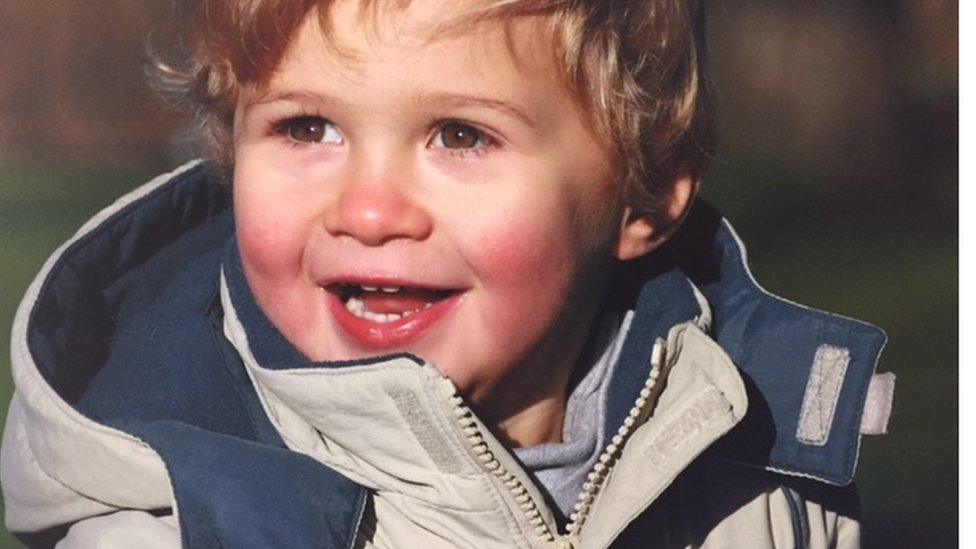

Jessica Mitchell, whose son, Dylan, was diagnosed with the cancer when he was two and has been left with disabilities, said treatment had essentially not changed much for "20 to 30 years".

"If there was a treatment out there that would have saved his life but also his quality of life - I would've been all over that at the time," she said.

Jessica and Dylan

Dylan was diagnosed with brain and spinal tumours in 2014 after ending up in A&E with a rash, screaming in agony, vomiting and clutching his head.

What followed was life-altering surgery, chemotherapy and radiotherapy.

"We were told he had brain tumours the size of a golf ball in his cerebellum," Jessica told the BBC. Surgery then confirmed their worst fears - the tumours were malignant.

"Because he was so young they suggested a chemotherapy-only option, so we consented to six months of chemo that was injected straight into his spine.

"We hoped at the end of the six months that we would go off and live life happily ever after.

"Unfortunately it wasn't to be," she said.

Beads of courage: some children with life-challenging illnesses collect special beads to commemorate each procedure or event they must endure throughout treatment. This is Dylan's collection.

A couple of months after coming off his chemo, Dylan relapsed really badly.

"His entire spinal column - from top to bottom - was covered in tumours and it was back in his brain as well," Jessica said.

"We were given an option to let him go home and die. That wasn't an option for us. So we opted to treat - but we had to treat very aggressively."

Because Dylan was so young, Jessica was told that the side-effects of treatment would be "life-limiting and life-altering" and she added: "Ultimately it was the only decision so we signed him up there and then."

Dylan was given radiotherapy and general anaesthetics five days a week.

"He was so sick and so weak that the radiotherapy team wasn't convinced he was going to make it," Jessica said.

"Dylan proved them all wrong, thankfully!"

In all, Dylan had four operations, 90 rounds of chemotherapy, 31 sessions of radiotherapy and 66 general anaesthetics.

The treatment has left him with profound disabilities, including brain injury, brain damage and spinal cord injury.

These photos show Dylan two years apart

Prof Steve Clifford, who is presenting the research at the Children with Cancer UK's Scientific Conference on Monday, said that in the future patients might not need to go through such aggressive treatment.

"This new discovery allows us to undertake studies to see how we could use these insights to personalise treatments according to the biological features of each patient's tumour," he said.

Cliff O'Gorman, of Children with Cancer UK, external, said investment in clinical trials was needed "to build on findings like this and make cutting-edge treatment and precision medicine a reality for all young cancer patients in the UK".

- Published25 June 2017

- Published31 March 2016