Lab-grown oesophagus implanted in mice

- Published

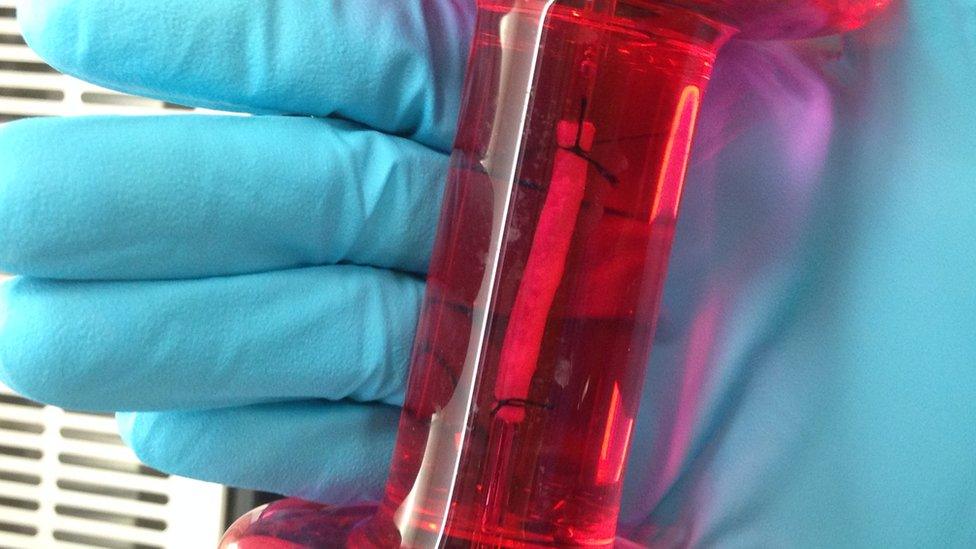

The lab-engineered oesophagus was capable of wave-like muscle contractions

Scientists in London have grown a bio-engineered oesophagus which was successfully implanted into mice.

The work, published in Nature Communications, external, was led by scientists at UCL Great Ormond Street Institute of Child Health (ICH), Great Ormond Street Hospital (GOSH) and the Francis Crick Institute.

The team hopes the research could eventually lead to clinical trials of lab-grown food pipes for children born with part of their oesophagus damaged or missing.

The oesophagus is a complex, multi-layered organ, made up of multiple tissue types, which acts as a pipe carrying food and liquid from the mouth to the stomach.

The team used a rat oesophagus, which was stripped of its cells, leaving behind a collagen scaffold.

They seeded it with early-stage muscle and connective tissue from mice and humans, and other early rat cells which went on to form the lining on the inside of the organ.

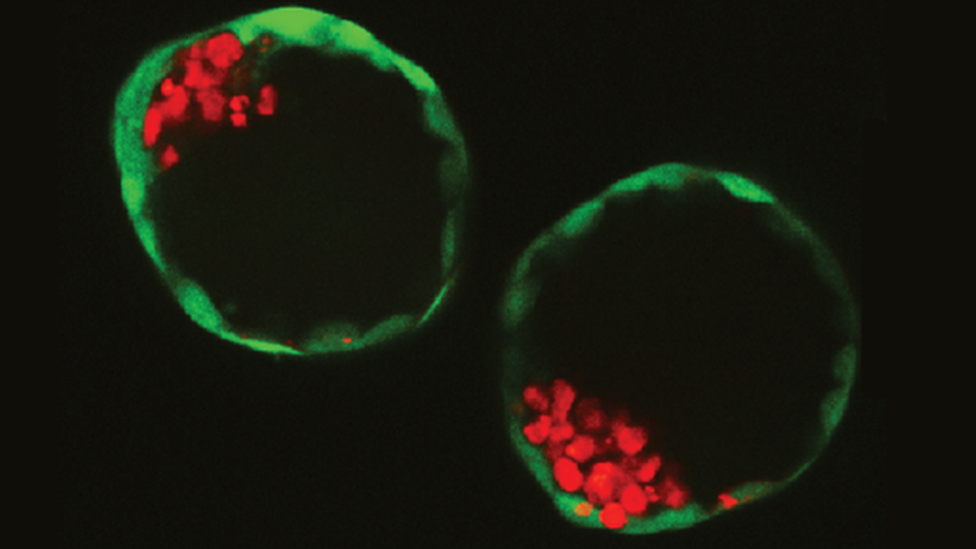

The use of stem cells from different species enabled researchers to differentiate between the origin of each tissue type which developed.

The 2cm sections of oesophagus were implanted into the abdomen of mice.

Dr Paola Bonfanti, co-author and group leader at the Francis Crick Institute and UCL Great Ormond Street Hospital Institute of Child Health (ICH), said: "We were amazed to see that our engineered tissue had both the structure and function of a healthy oesophagus, and hooked up with nearby blood vessels within a week of transplantation."

The sections of oesophagus were capable of muscle contraction, which is needed to move food down to the stomach.

Around one in 3,000 babies is born with abnormalities of the oesophagus, usually involving a gap between the upper and lower section, or where it does not connect with the stomach.

Hudson, who was born with part of his oesophagus missing, and his twin brother, Hank

Prof Paolo De Coppi, co-author and consultant surgeon at Gosh, and head of stem cells and regenerative medicine at ICH, said: "This is a major step forward for regenerative medicine, bringing us ever closer to treatment that goes beyond repairing damaged tissue and offers the possibility of rejection-free organs and tissues for transplant."

There are several years of research required before this might be ready for clinical use, including more animal trials, involving larger mammals.

The eventual aim would be to create bio-engineered organs from a pig oesophagus, which would be injected with a patient's own stem cells, in order to minimise the risk of rejection.

Hudson Wakelin, aged two, was born without part of his oesophagus.

He has had surgery at Gosh to lift his stomach up into his chest in order to connect it directly to his throat.

It now means he can eat some of the same meals as his twin, Hank, but needs careful eating support to ensure food does not get into his windpipe.

His mum, Nicola, said: "Hudson has to eat little and often. We have to be careful that he doesn't choke, and he suffers from reflux, bringing up food and stomach acid, which can create problems."

Nearly 250 children a year are born in the UK with Hudson's condition, known as oesophageal atresia, and the research is aimed at helping those where current surgical options bring limited benefits.

The field of engineered organ transplants suffered a major setback in 2016 when a surgeon in Sweden, Paolo Macchiarini, was accused of falsifying his science.

Of nine patients who received a synthetic windpipe, seven died, and the two survivors had the organ replaced with a donor trachea.

The team at the Crick and Gosh say the scandal reinforced their determination to proceed cautiously.

Follow Fergus on Twitter., external

- Published3 May 2018

- Published3 August 2018