Deadly Ebola outbreak 'not global threat'

- Published

The BBC's Anne Soy reports from the Uganda-DR Congo border

The World Health Organization has decided not to declare a global emergency over the Ebola crisis in the Democratic Republic of Congo.

The WHO said Ebola was "very much an emergency" in the region, but it did not pose a global threat.

However, it was damning of countries for giving less than half the money needed to deal with the disease.

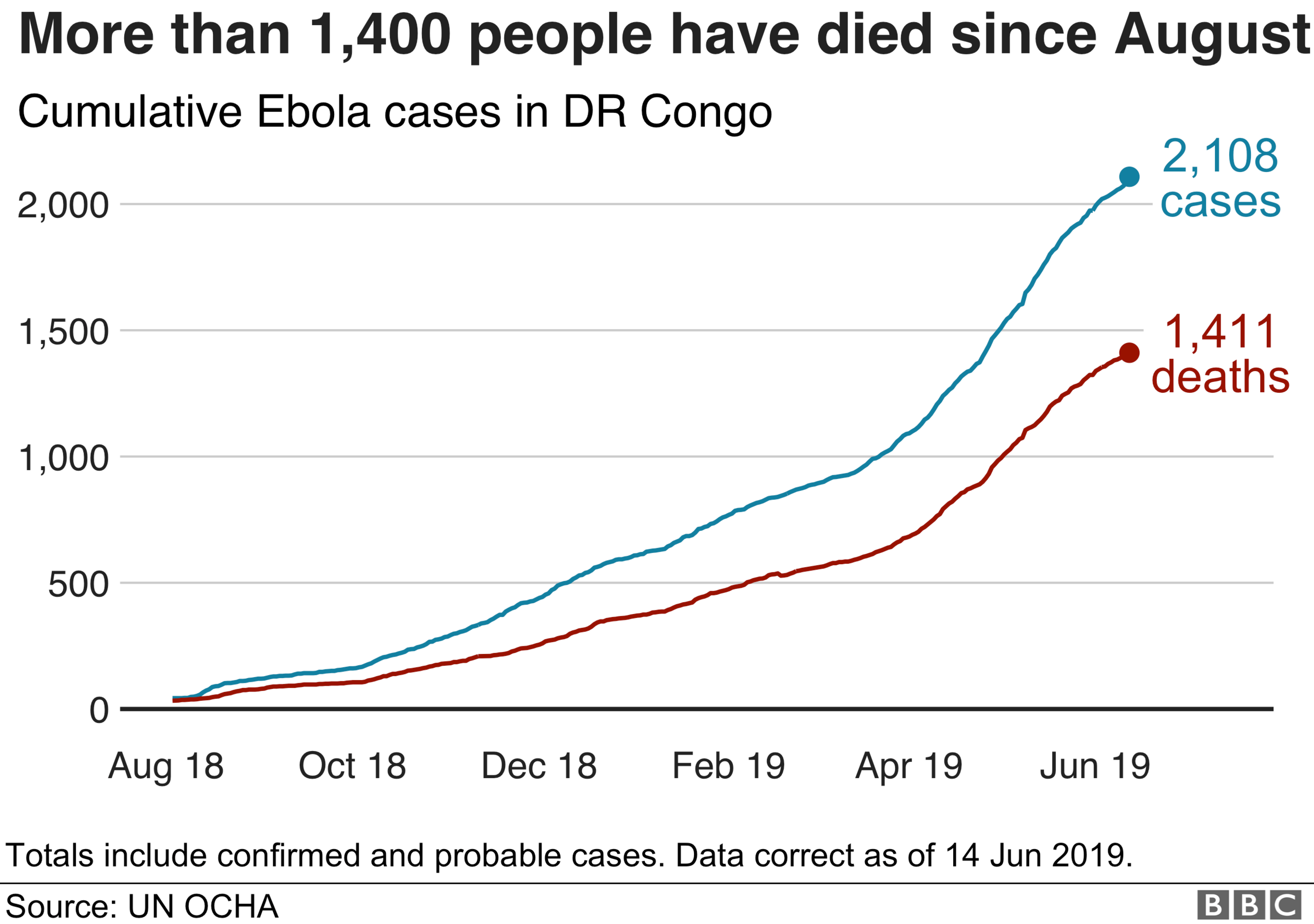

The deadly outbreak - the second largest in history - has killed more than 1,400 people.

This week cases were detected across the border in Uganda, though the virus is not yet spreading there.

Declaring a Public Health Emergency of International Concern is one of the most important acts the WHO can take.

It has done so only four times before - including for the Ebola outbreak in West Africa which killed more than 11,000 people.

Such a decision usually means getting more money and healthcare workers to tackle an outbreak - or political support to stop the fighting to let medics get the job done.

So why is Ebola not a global emergency?

This was not a straightforward decision.

Dr Preben Aavitsland, the acting chair of the WHO's emergency committee, said there was extensive debate and differing views at the emergency meeting.

The outbreak met some of the criteria for a global emergency as it was both an extraordinary event and risked international spread.

However, he said efforts on the ground "would not be enhanced" by declaring an emergency.

Dr Aavitsland said: "This is not a global emergency, it is an emergency in DRC, it is a severe emergency."

But he warned declaring an emergency could lead to border closures or airlines refusing to fly to DRC, which could do more harm than good.

"There is nothing to gain, but there is a lot to lose," he said.

The WHO has previously discussed whether the Ebola outbreak in DRC should be declared an emergency on two occasions.

Both times it decided not to, in part because Ebola was deemed a threat in only in the region rather than internationally.

How bad is the situation in DRC?

The outbreak started in August 2018 and is affecting two provinces in DRC - North Kivu and Ituri.

More than 2,100 people have been infected and over 1,400 have died.

It took 224 days for the number of cases to reach 1,000, but just a further 71 days to reach 2,000.

There are some positive signs with the number of new cases slowing - there were 54 cases in the past week, external compared with 88 in each of the two previous weeks.

However, 54 cases is still more than the totality of many Ebola outbreaks.

Tackling the disease has been complicated by conflict in the region - between January and May there were more than 40 attacks on health facilities.

Another problem is distrust of healthcare workers with about a third of deaths being in the community rather than at a specialist Ebola treatment centre.

It means those people are not seeking treatment and risk spreading the disease to neighbours and relatives.

Has the virus spread to other countries?

Two people have died from Ebola in neighbouring Uganda - a five-year-old boy and his 50-year-old grandmother.

They were members of a family that crossed the border from DRC.

While the WHO says such cases are of "grave concern" is says there is no evidence of the virus spreading in Uganda.

Twenty-seven people are said to have been in contact with the infected family. They have all been restricted to their homes and will be offered the Ebola vaccine.

Is the world doing enough to help?

The WHO is clear that more needs to be done.

It said that between February and July it needed $98m to tackle the outbreak, but it was facing a shortfall of $54m.

Sir Jeremy Farrar, from the Wellcome medical research charity, said: "A step up in the response with full international support is critical if we're to bring the epidemic to an end and ensure protection for the communities at risk.

"The response in DRC remains overstretched and underfunded."

What is Ebola?

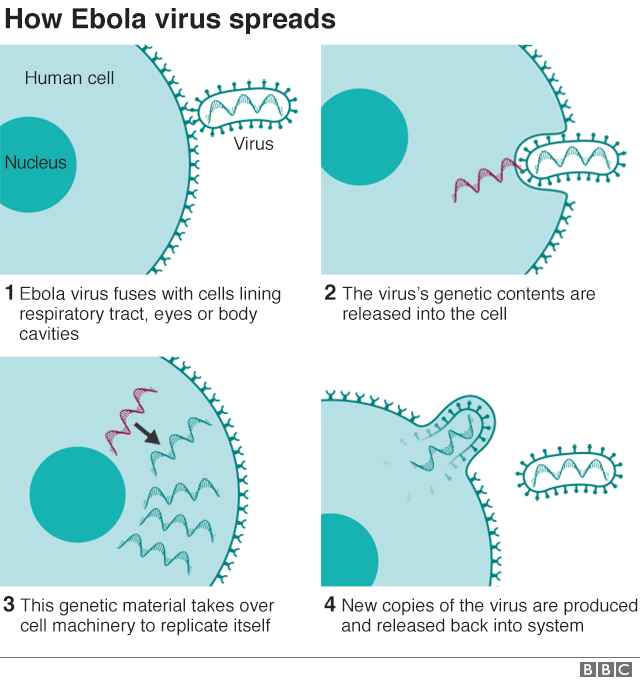

Ebola is a virus that initially causes sudden fever, intense weakness, muscle pain and a sore throat.

It progresses to vomiting, diarrhoea and both internal and external bleeding.

People are infected when they have direct contact through broken skin, or the mouth and nose, with the blood, vomit, faeces or bodily fluids of someone with Ebola.

Patients tend to die from dehydration and multiple organ failure.

- Published28 March 2019

- Published7 March 2019

- Published5 April 2019