Coronavirus: Scientists use genetic code to track UK spread

- Published

Prof Hiscox's team are using MinION, a hand-held sequencer developed by Oxford Nanopore Technologies

Scientists are analysing the unique genetic code of individual samples from infected patients to track how the coronavirus is spreading across the UK.

Each sample of its genetic material, RNA, reveals another step in the chain of infections - who infected whom.

University of Liverpool scientists can also identify other viruses and bacteria in patients' throat swabs.

And this may help explain why some patients with no known underlying health conditions become seriously ill.

"The aim is to find out who is getting sick, what kind of illness they have and why - is it the virus that is causing it, is their immune system over-responding or do they have some kind of super-infection?" chief investigator Prof Calum Semple told BBC News.

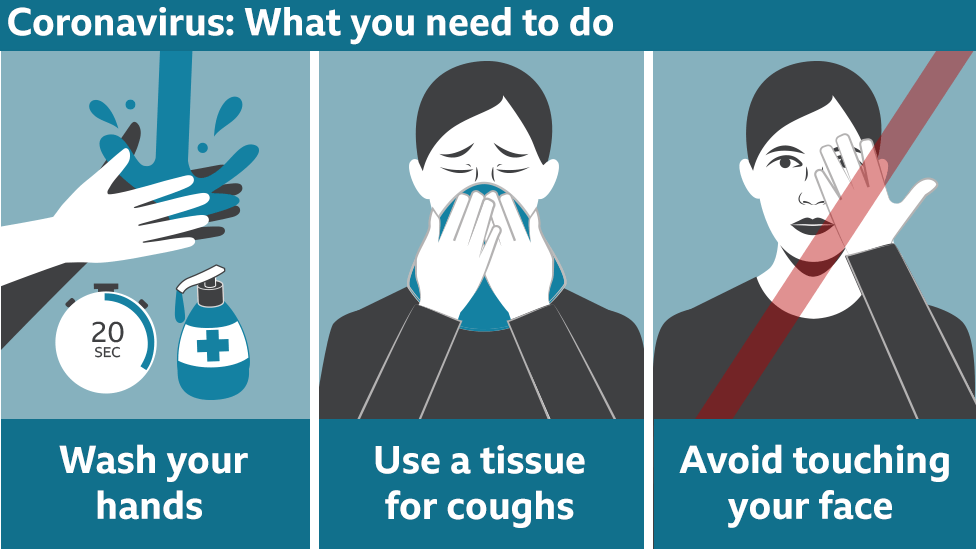

EASY STEPS: How to keep safe

A SIMPLE GUIDE: What are the symptoms?

GETTING READY: How prepared is the UK?

MAPS AND CHARTS: Visual guide to the outbreak

A similar approach was used to track the Ebola outbreak in West Africa in 2015.

Prof Tom Solomon, director of the Institute of Infection and Global Health, at the University of Liverpool, told BBC News: "We have some patients where we have no idea how they were infected - but by looking at their genetic material and comparing it with others, we can fill the missing link, like a detective story, and that may help control the outbreak in the long term."

Coordinated at the University of Liverpool, the Clinical Characterisation Protocol involves scientists at several other universities, including Edinburgh, Oxford, Bristol and Glasgow.

Early findings, external show they can sequence the RNA of the coronavirus and the rest of the respiratory microbiome in eight hours.

Team leader Prof Julian Hiscox, who has been studying another coronavirus, Middle-East respiratory syndrome (Mers), for the past two years, with scientists in Saudi Arabia, told BBC News: "We found with severe Mers cases, people tend to die because they have other co-infections as well, such as klebsiella, which can cause pneumonia.

"We can now identify all the underlying microbiome, the viruses and bacteria in the patient samples, so we can feedback to clinicians that they may have a bacterial infection which could be treated with antibiotics."

Prof Hiscox's team are using MinION, a hand-held sequencer developed by Oxford Nanopore Technologies.

Mers, which emerged in 2012, has caused more than 800 deaths.

It has a mortality rate of one in three, far higher than Covid-19, but is far less contagious.

Follow Fergus on Twitter., external

- Published29 January 2015

- Published29 January 2018