Coronavirus: Is the PM trying to achieve the impossible?

- Published

Boris Johnson: "We are taking the first careful steps to modify our measures"

The prime minister is effectively trying to pull off the impossible.

He wants to try to restart normal life, while keeping the virus at bay with limited means to do so.

With no vaccine, the government is reliant on containing any local outbreaks.

But the problem is that even with the extra testing that has been put in place over the past month, there are big holes in the UK's ability to suppress the virus.

It takes too long to get test results back - several days in some cases - and those most in need of regular testing, such as care home staff for example, are still reporting they cannot always access tests.

Our ability to trace the close contacts of infected people remains unknown - the piloting of the system, which involves the use of an app and an army of contact tracers, has just started on the Isle of Wight.

It means we are effectively fighting this "invisible killer" with one hand behind our back.

Should we be in a better position?

We are not alone in struggling, similar problems are being encountered by other countries.

But we are still some way behind the best prepared and equipped, such as Germany and South Korea.

Could it be any different? Should it be any different?

Some argue we were too slow to react to the growing threat.

For example the UK largely relied on a network of eight government testing labs for the best part of two months following the first diagnosed coronavirus case.

Eventually other partners were brought on board, but it meant until late April we were still only able to do 25,000 tests a day.

Others have picked holes in the strategy taken.

The care sector, for example, believes more should have been done to protect care homes, given the rising number of deaths that are being reported - there are indications that these account for half of all deaths now.

LOCKDOWN: How will it change now?

THE R NUMBER: What it means and why it matters

LOOK-UP TOOL: How many cases in your area?

EXERCISE: What are the guidelines on getting out?

SCHOOLS: When will children be returning?

What about the damage of lockdown?

Then - on the flip side - there are the difficulties the lockdown itself is causing.

It has had a huge economic and social impact as well as harming health - referrals for cancer care are down, while visits to A&E have dropped by a half since the epidemic started.

Is this being factored in enough?

Schools in England are being given a tentative green light to return, but only certain years.

Yet children are the least likely to develop serious symptoms - and some evidence suggests they may not pass on the virus that easily.

It is partly because of this that some question whether we should even be so obsessed by keeping the infection rate of the virus down below one - the so-called R number which refers to the average number of people an infected person passes the virus to.

The prime minister committed to this in his address, but with the R currently at between 0.5 and 0.9 there is virtually no wriggle room to lift the restrictions that are in place without it going above one.

However, last week academics from Edinburgh and London universities published modelling suggesting the virus could be allowed to spread in a controlled way in the healthy population if the vulnerable were shielded.

The R could be safely left to rise towards close to two if this were to happen.

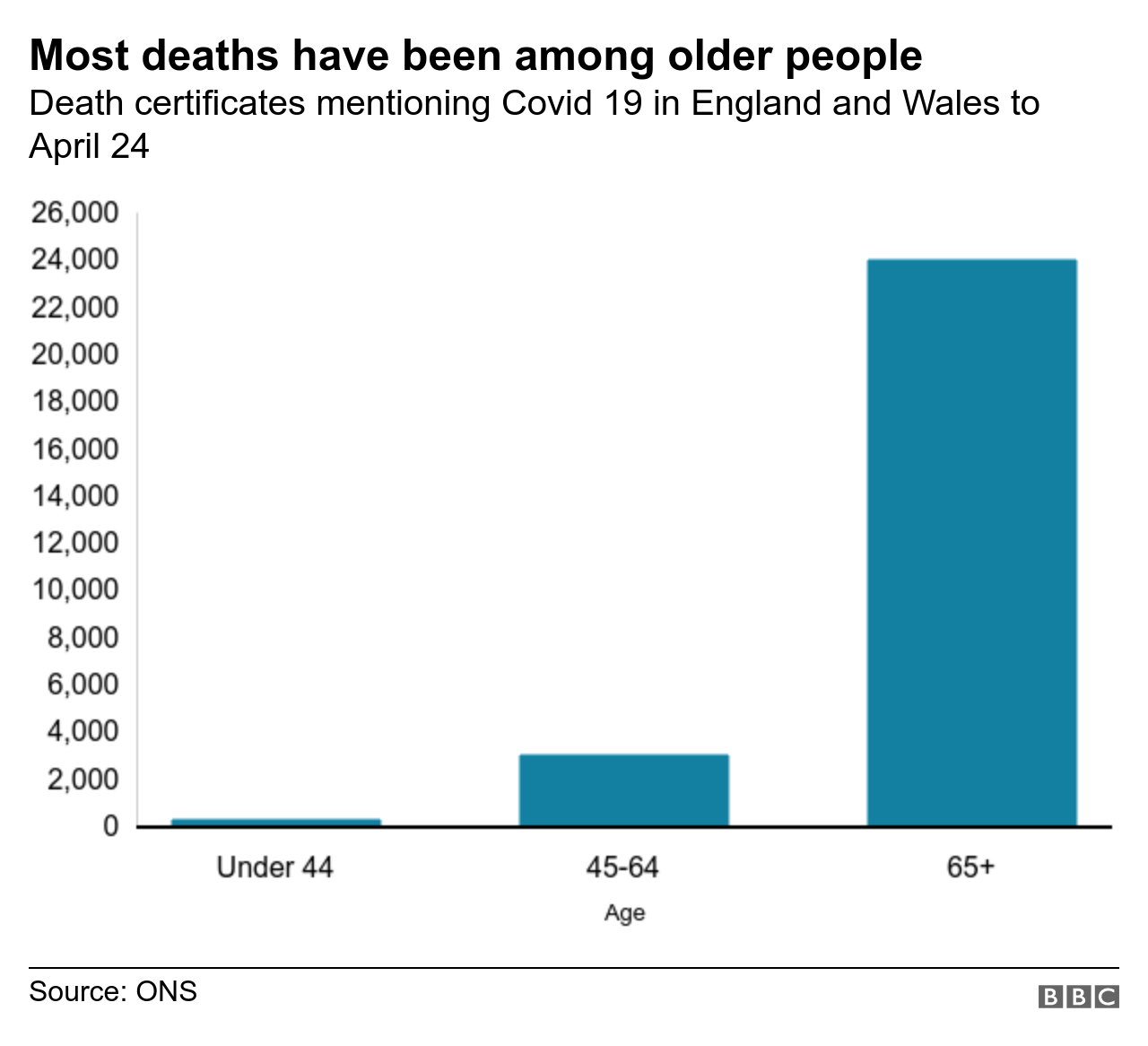

The theory being that the overwhelming majority of the risk of serious illness and death lies with older people or those with health conditions.

Prof Sir David Spiegelhalter, one of the country's leading statisticians and a government adviser, pointed out the risk to anyone under 25 was "trivial", while researchers at Stanford University have said deaths in anyone under 65 without a pre-existing illness are "remarkably uncommon".

It means the initial reaction to the statement - the government is planning to published more detailed guidance about its plans on Monday - is one of frustration, certainly in the scientific and medical community.

Prof Trish Greenhalgh, a health care expert from the University of Oxford, perhaps best sums it up.

She is worried we could now find ourselves in the "worst of both worlds" by both trying to move forward and kick-start the economy (by encouraging people to return to work) while maintaining the lockdown is effectively still in place.

Employers will not yet have worked out how social distancing can be incorporated into everyday life, while its not clear how the public transport system can cope with more passengers given the reduction in service that has been seen during lockdown.

It is, she says, the "have cake and eat it" maxim.

- Published16 April 2020

- Published29 April 2020

- Published30 March 2020

- Published4 August 2019

- Published6 January 2019

- Published8 February 2017

- Published8 February 2017

- Published6 January 2017