How bad is our obesity problem?

- Published

Obesity has been linked to deprivation

Prime Minister Boris Johnson is promising to set out an ambitious programme to tackle obesity in the coming days.

The plan is likely to include a ban on junk food advertising before 9pm and restrictions on in-store promotions.

It's no coincidence this is being launched in a middle of pandemic, which has seen tens of thousands of people die or left dealing with potentially long-term health problems after being infected with coronavirus.

Research suggests being overweight puts people at higher risk of complications from the virus - once again emphasising the toll obesity is taking on the health of the nation. So how bad is the problem?

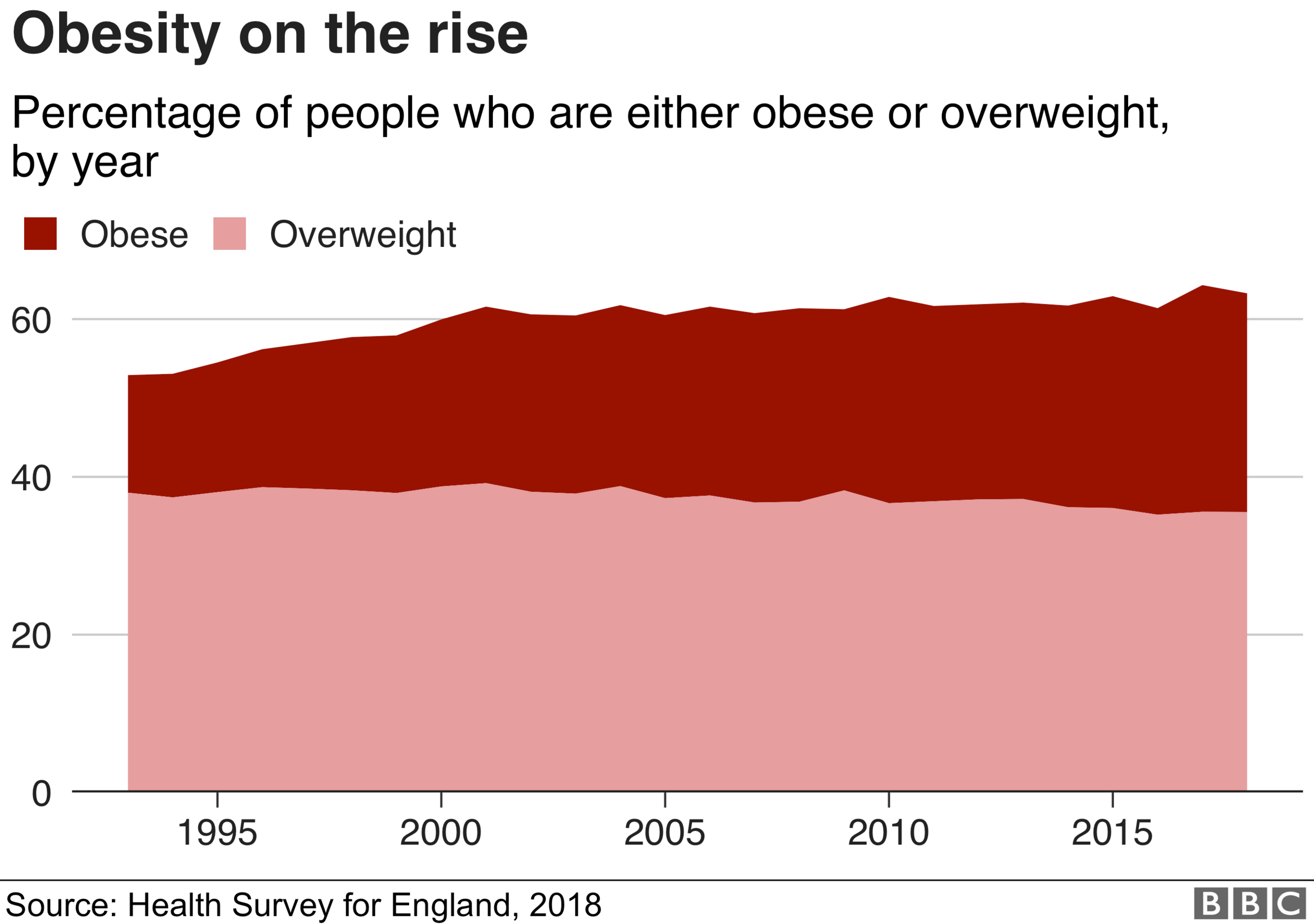

Nearly two-thirds of adults are classed as overweight, with more than a quarter deemed obese - according to data from NHS Digital.

Rates have risen since the early 1990s - at first rapidly, although more slowly over the past 10 years, suggesting some of the subsequent measures taken, as well as awareness-raising about the problem, have started to alter our behaviour.

Men are slightly more likely to be obese than women.

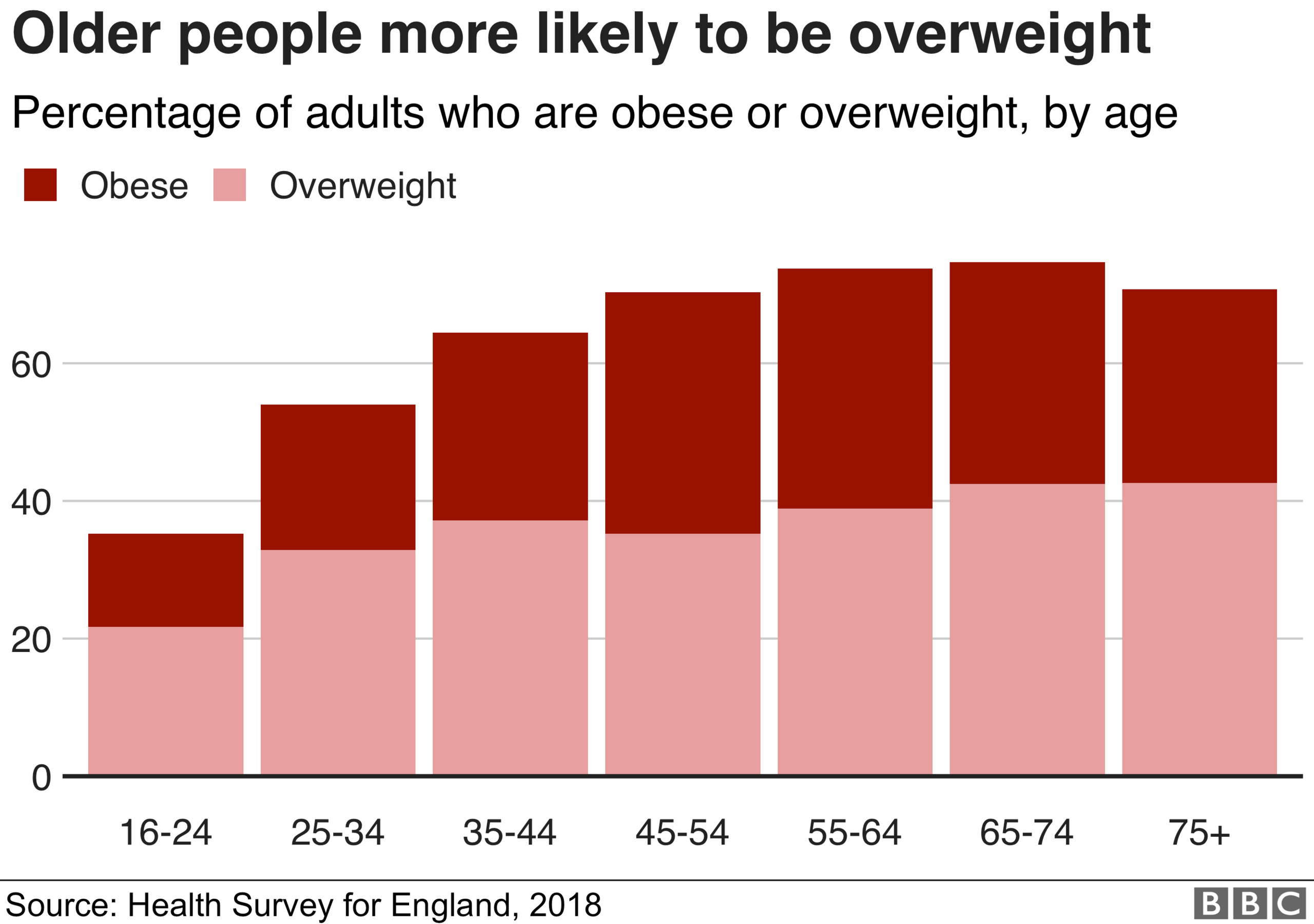

It also differs by age group, with the proportion of people who are overweight rising as people get older, peaking in the mid-50s to mid-60s.

As well as putting people at risk of complications from coronavirus, being obese is also linked to a higher risk of other conditions - from heart disease, type 2 diabetes and cancer, to problems during pregnancy and joint pain.

Clear link with deprivation

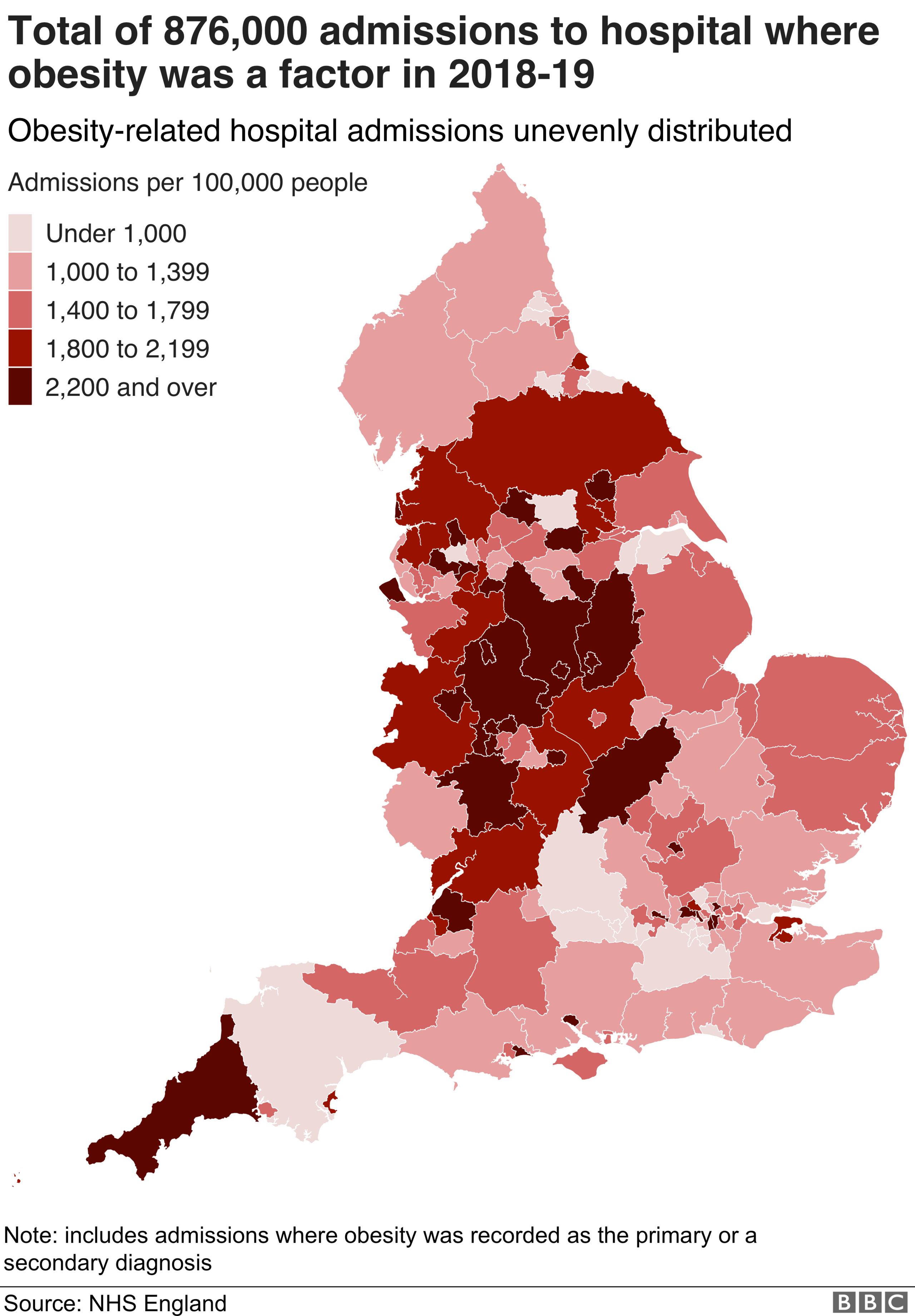

The high rates of obesity take such a toll on our health that 876,000 hospital admissions were linked to weight problems in 2018-19.

The rate of those admissions varies quite significantly across the country, with areas in the Midlands and north of England tending to see higher rates than other parts.

Wigan, Wirral, York, Stoke-on-Trent and Nottingham all recorded admission rates of over 3,000 per 100,000 population.

That compares to the likes of Wokingham and West Berkshire, which both saw rates below 500 per 100,000 population.

There is a clear link with deprivation - overall those in the most deprived areas are two-and-a-half times more likely to be admitted to hospital with obesity listed as a factor.

Problems start in childhood

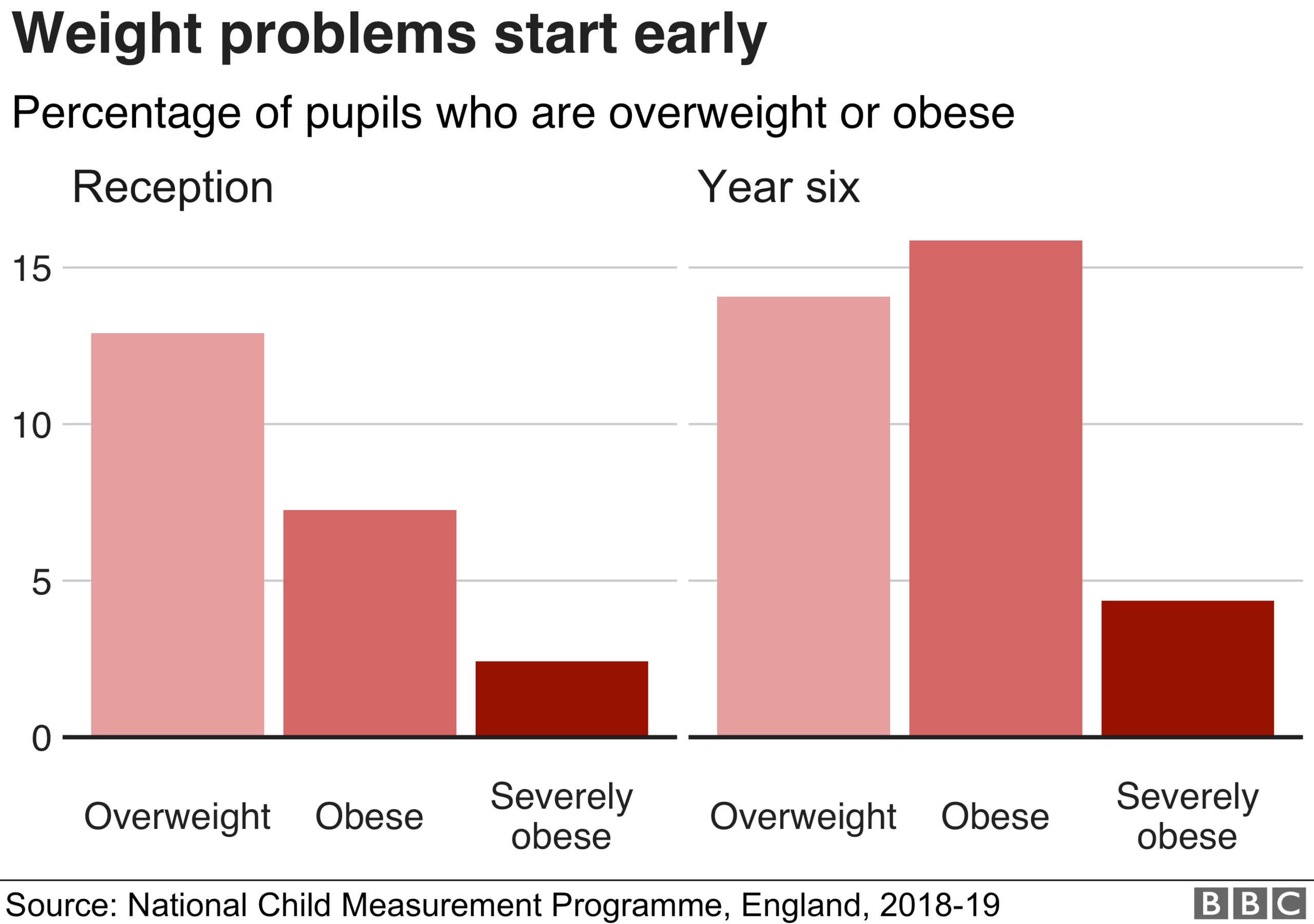

And this is not just an issue for adults. Thanks to the National Child Measurement Programme, which tracks obesity rates in schools across the country, we have clear data for primary school children.

It shows one in 10 children in reception year are obese, rising to one in five by the end of primary school.

If you include children who are overweight, the proportions rise to one in five and one in three respectively.

It is why the Royal College of Paediatrics and Child Health has described the obesity issue as "one of the greatest threats" to children and society as a whole.

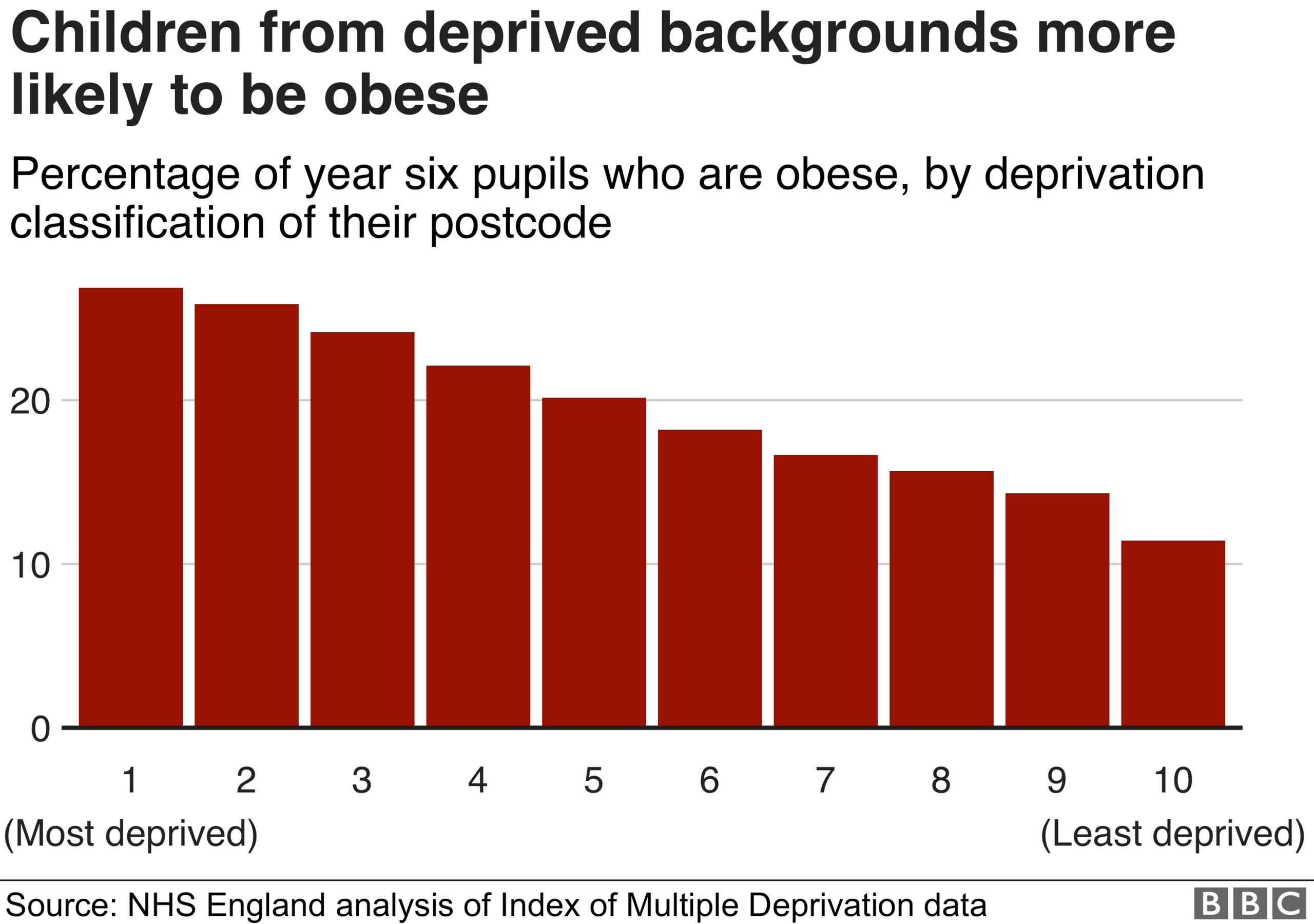

And, once again, the highest rates are seen in the most deprived areas.

Why is this? There is plenty of debate about the exact causes.

But certainly the so-called obesogenic environment plays a crucial role - research shows poorer areas have fewer opportunities for physical activity and a greater concentration of fast food outlets.

England is not alone

It goes without saying that obesity is not an England-only problem. Scotland, Wales and Northern Ireland have almost identical levels.

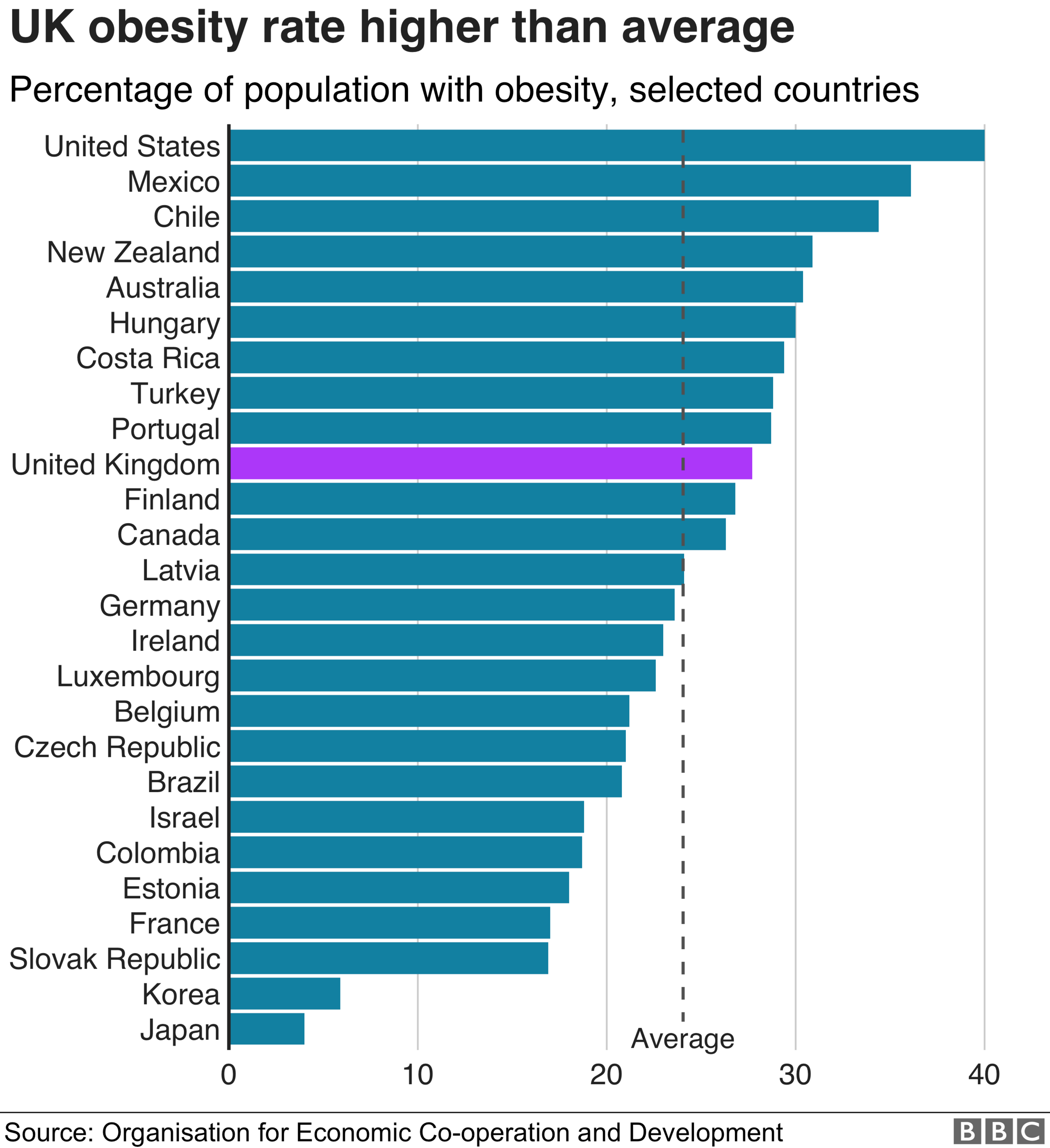

But around the world, rates do vary quite significantly.

Less than 10% of adults in South Korea and Japan are obese, compared to 40% in the US.

The UK's rates are a little above average, greater than a number of our near neighbours, including Germany and France.

Attempts to get the rate down have undoubtedly not been helped by the turbulent nature of our politics in recent years and the changes in prime minister.

In 2015, David Cameron's government was briefing that an ambitious obesity strategy was being planned.

The contents are remarkably similar to what the government is talking about now: bans on TV advertising of junk food before 9pm and restrictions on supermarket in-store promotions, alongside the sugar levy on soft drinks.

But the mood music changed when Theresa May took over. A much watered-down plan was published in the middle of summer recess in 2016 and many of the tough measures dropped - although the sugar levy went ahead.

But in 2018 a new plan - or updated plan, as it was couched - was published, re-emphasising the need for action.

When Boris Johnson became prime minister the following year he sounded unconvinced, calling for a review of so-called sin taxes.

It now looks like his appetite for action has changed too.

Follow Nick on Twitter, external

- Published16 April 2020

- Published29 April 2020

- Published30 March 2020

- Published4 August 2019

- Published6 January 2019

- Published8 February 2017

- Published8 February 2017

- Published6 January 2017