Covid: Are care homes ready for the second wave?

- Published

In the first wave of the coronavirus pandemic, care homes looking after older and disabled people saw a very high number of deaths among residents.

As we enter a second lockdown, what have we learned?

What happened during the first wave?

In early spring, the national effort was focused on preventing hospitals being overwhelmed, increasing the number of ventilators and building new Nightingale hospitals.

There was little mention of social care, which supports people in their own homes and in care homes.

In March, care providers warned they were struggling to find and pay for increasingly expensive personal protective equipment (PPE), get tests for staff or residents, or find clear guidance for care home visits.

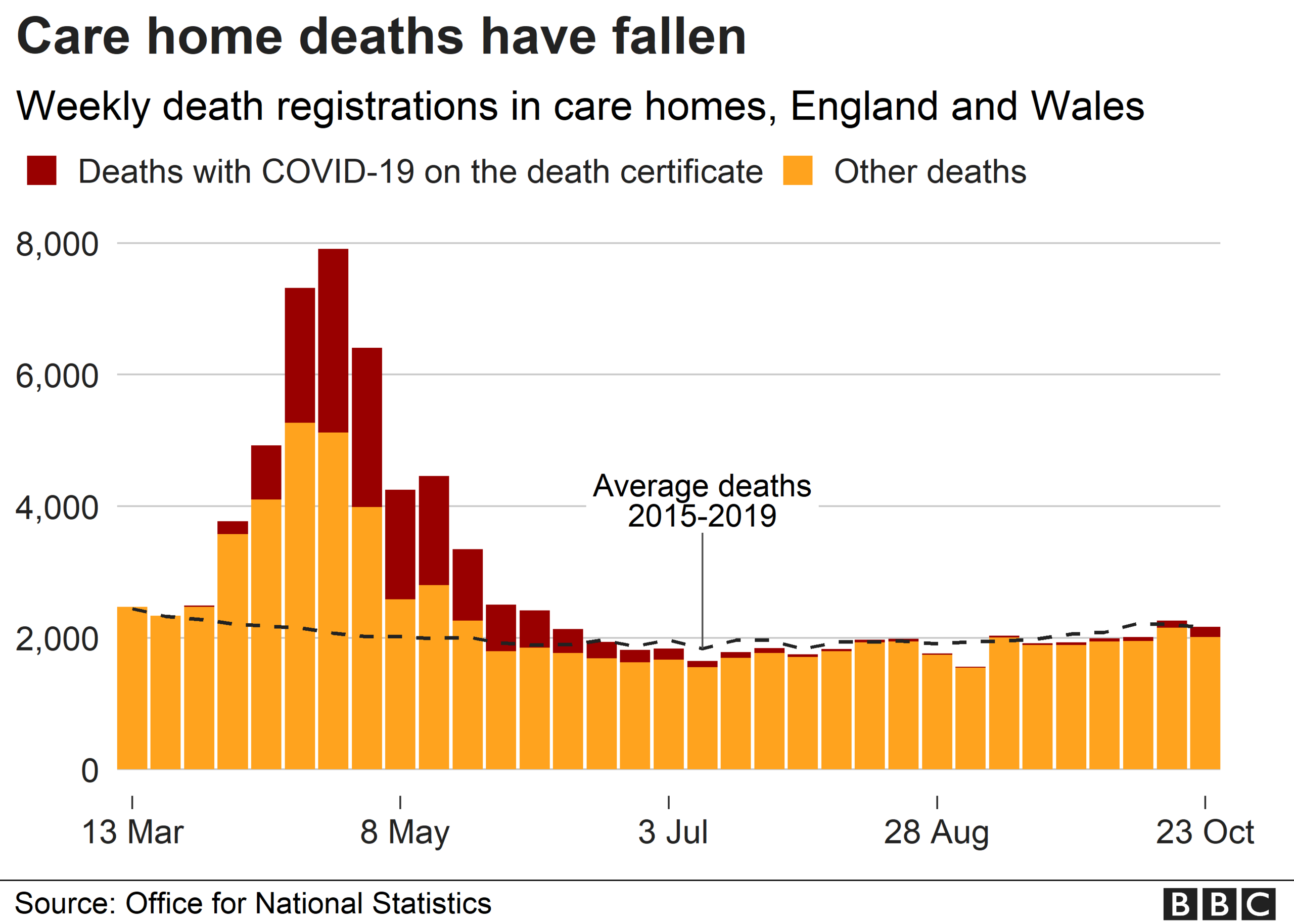

In total, about 16,000 people have died with coronavirus, external in English and Welsh care homes (up to 23 October). Excess deaths in care homes - the number of deaths above average for that time of year - are as high as 25,500.

Almost 90% of these deaths happened during April and May.

How did the virus get into care homes?

There were a number of ways the virus could have entered care homes, including:

Discharging of hospital patients into care homes at the start of the pandemic

Staff working and moving between different care homes

People visiting care homes

Is there enough testing in care homes now?

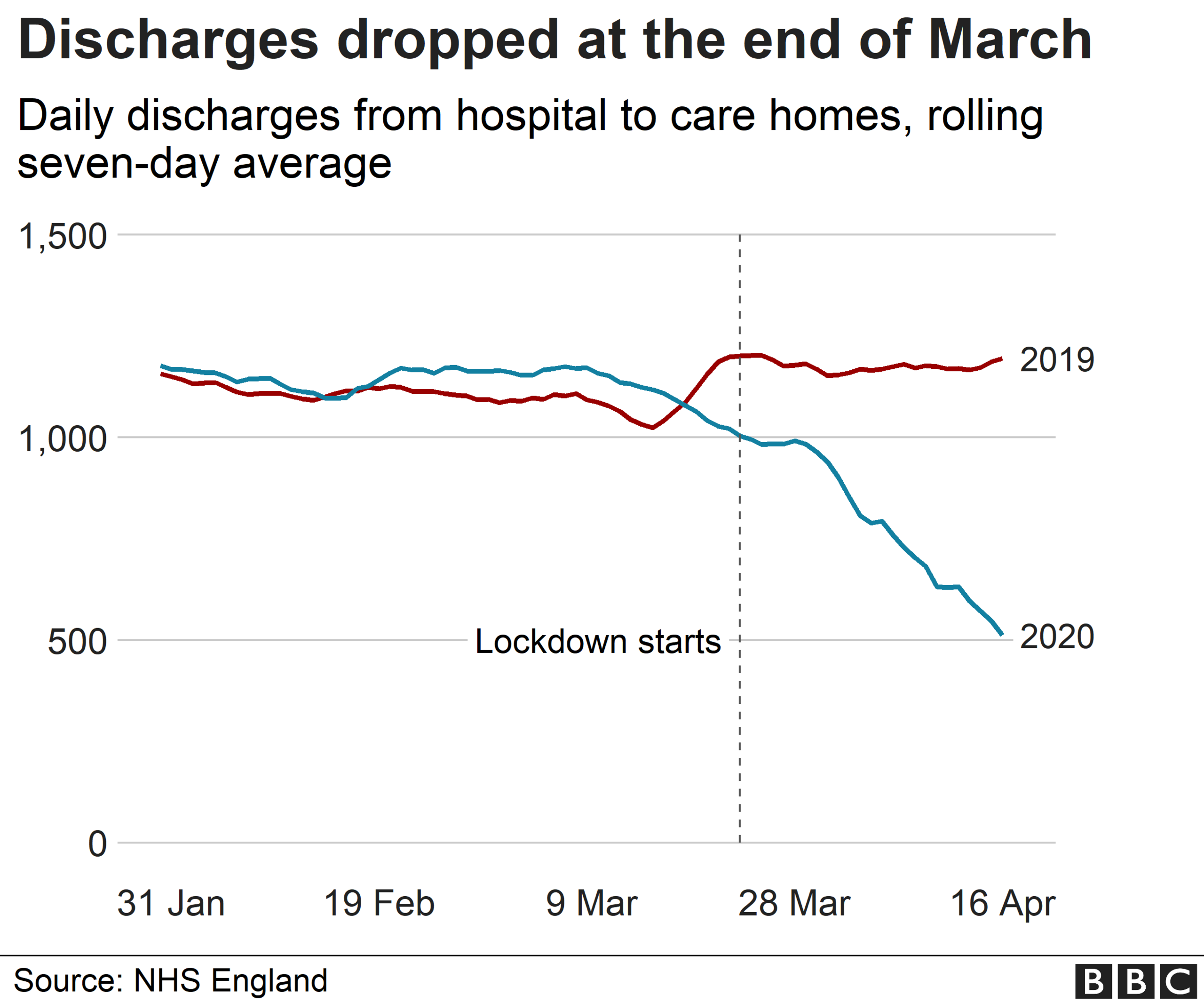

On 15 April, Health and Social Care Secretary Matt Hancock announced that all people being discharged into care homes from hospital, external needed to have a coronavirus test.

By that point, 28,000 people had been transferred from hospitals to care homes, external since the first coronavirus death.

A BBC Freedom of Information request showed about three-quarters of these patients had not been tested before being discharged.

Testing was also made available to care staff with symptoms. However, a significant number of staff and residents had the virus without symptoms.

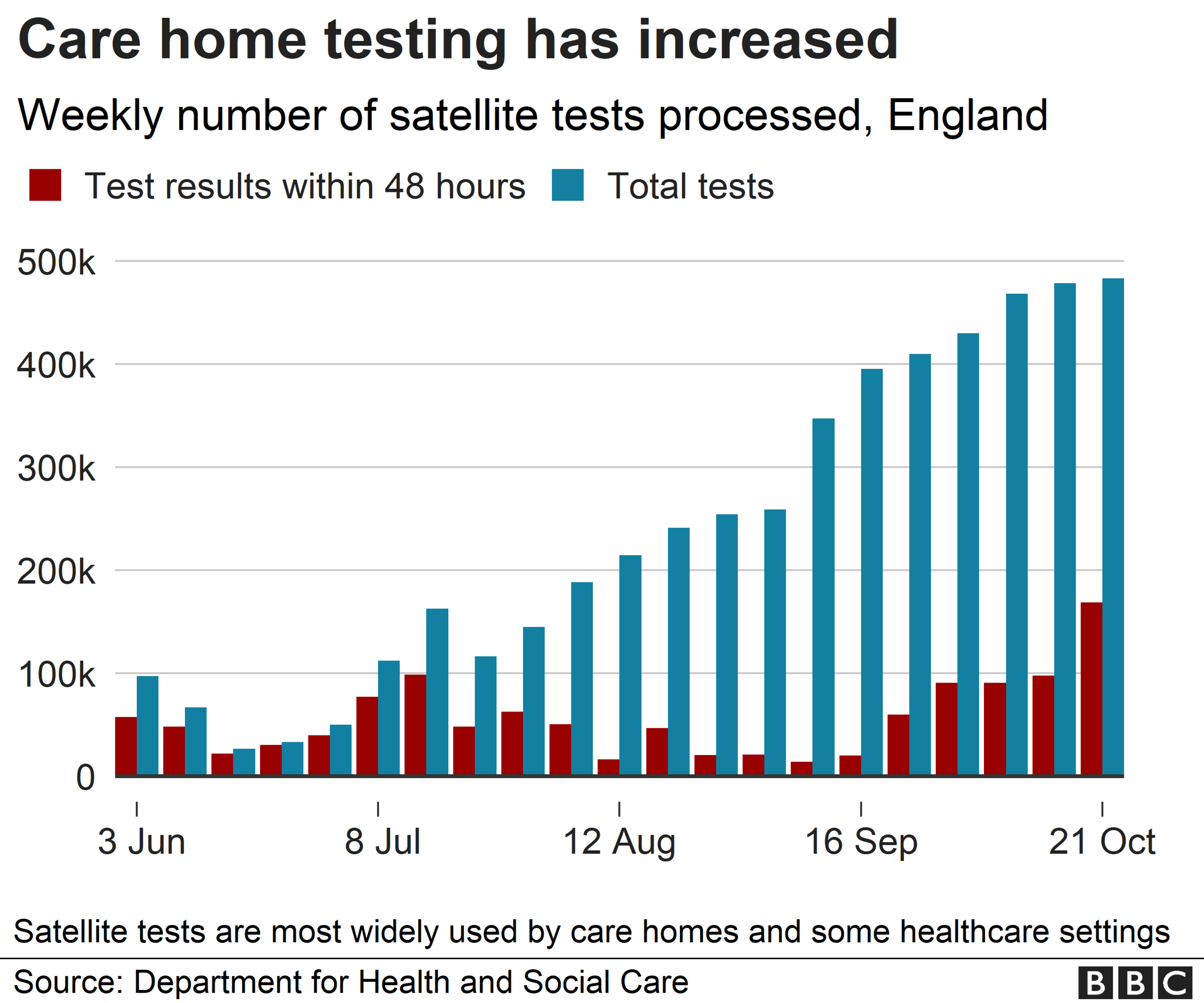

On 28 April, testing was extended to all staff and residents, regardless of whether they had symptoms. And in early July, care homes were told staff would be tested weekly and residents every month.

Many care providers see testing as the single most important tool they have in managing the virus.

There has been criticism that the rollout of testing in care homes has been slow. However, by the beginning of September all homes had access to regular testing. Nevertheless, at times there have been delays in the results coming back.

An average of 430,000 satellite tests have been carried out each week since September. The turnaround time for results has improved from an average of 103 hours to 53 hours.

Satellite tests are those dropped off in bulk at specific places that use large numbers of tests - in particular care homes - and picked up a few days later once all the tests have been carried out.

There is now increasing pressure for the relatives of residents to have access to testing, in particular those with dementia.

But until that happens, even during lockdown, the government has issued guidance saying visits are allowed in controlled settings. This might mean visits continuing through windows, or in ventilated visitor pods.

These plans have been criticised, with the Alzheimer's Society saying the plan "completely misses the point" and will be distressing for residents. Labour has said homes will not have the money to implement the necessary measures.

Is there enough personal protective equipment?

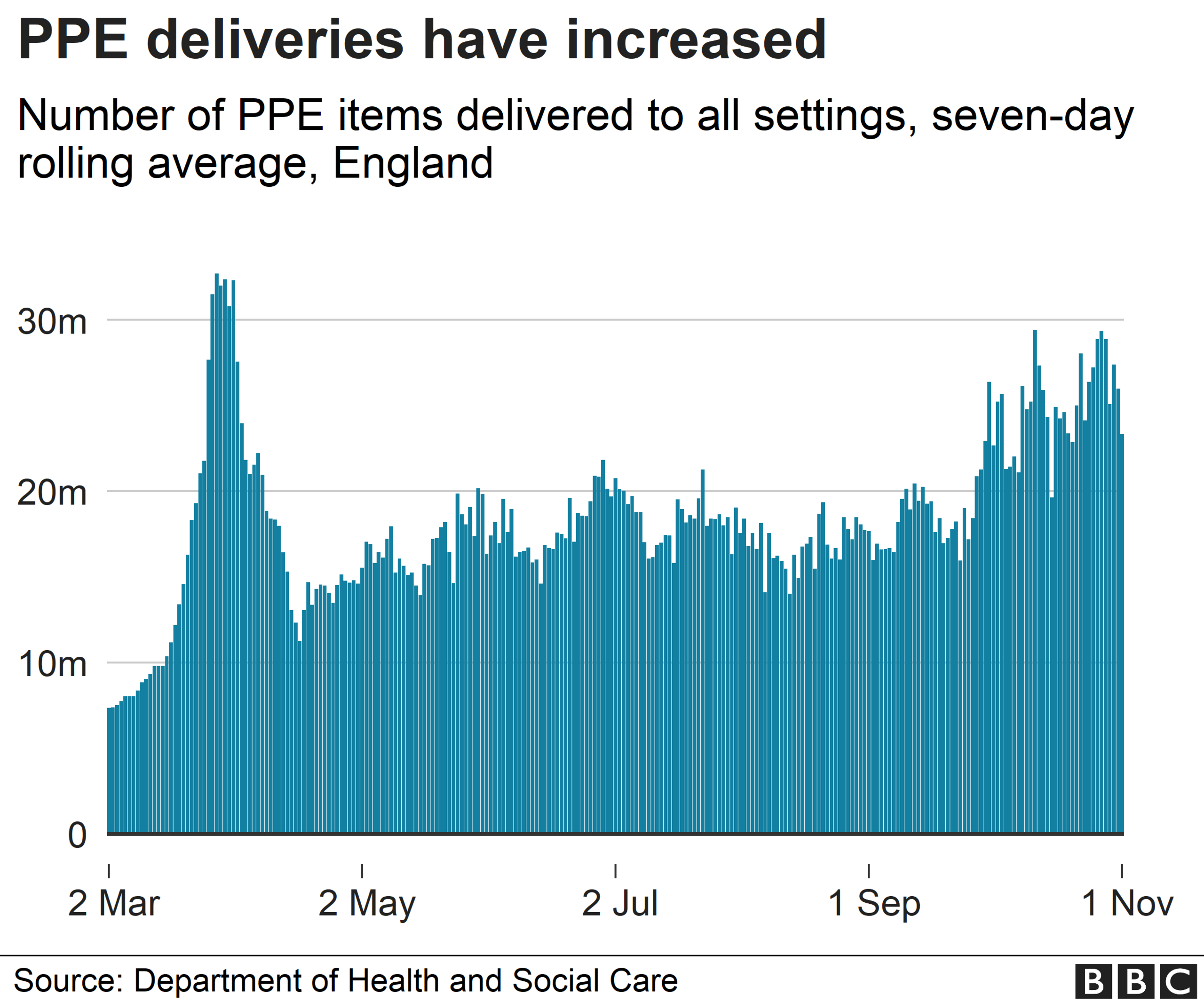

Before the pandemic, there was only limited use of gloves, aprons and in particular, masks, in care homes.

But the arrival of coronavirus meant a sharp increase in the demand for PPE.

Care companies said costs increased dramatically and some reported that their regular supplies were diverted to the NHS, which was also struggling.

Production of PPE supplies appears to have caught up with demand. Some care providers have even been able to stockpile supplies over the summer.

To date, 4.6 billion items of PPE have been delivered across health and social care settings, external.

In the adult social care winter plan, external, published on 18 September, the government said it would provide free PPE for care services until March 2021.

This means care providers are allocated a certain amount of equipment depending on the number of people they look after.

Homes buy additional supplies as normal.

Better recognition for care home staff

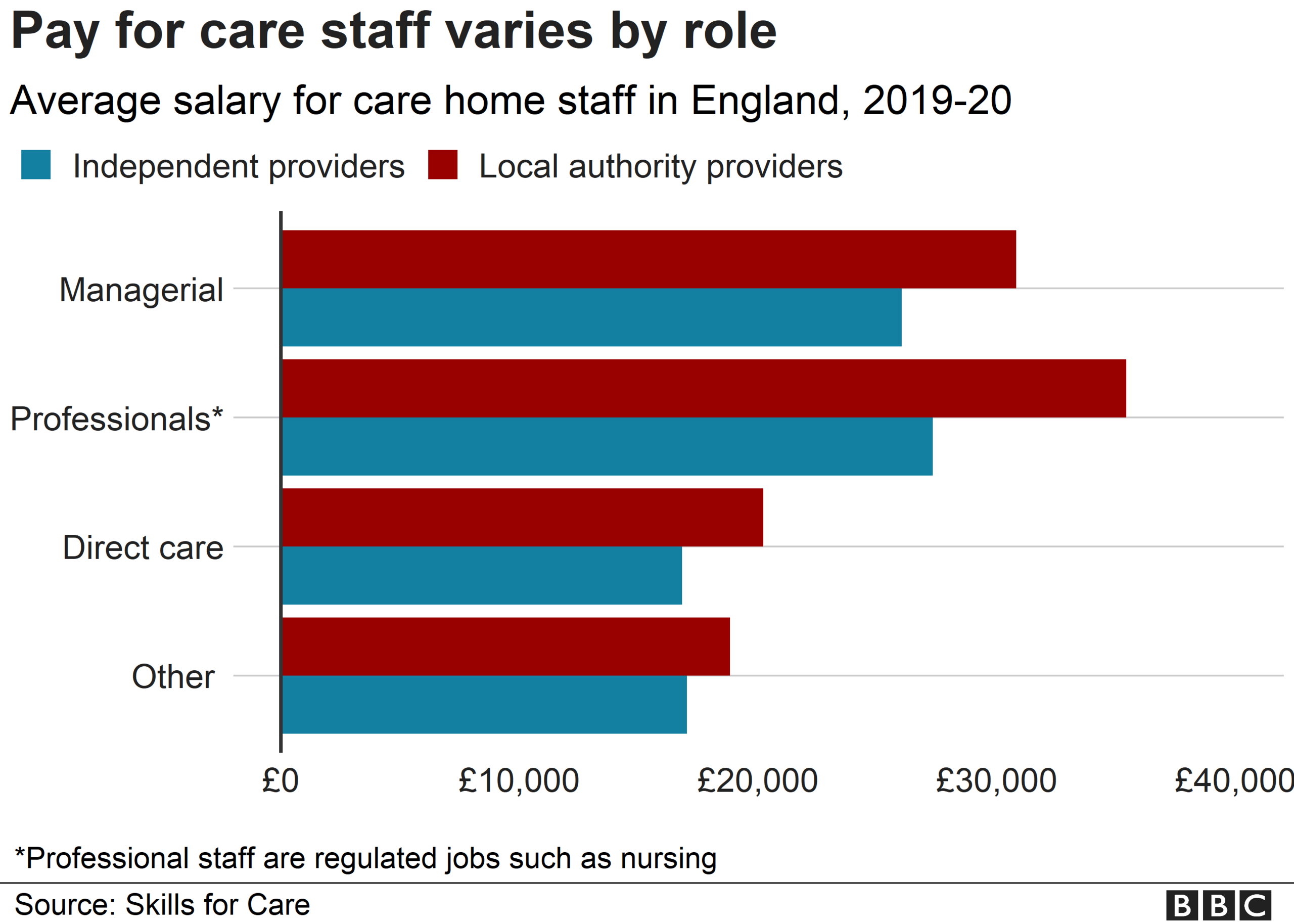

Care staff are generally poorly paid and certainly before the pandemic, poorly recognised.

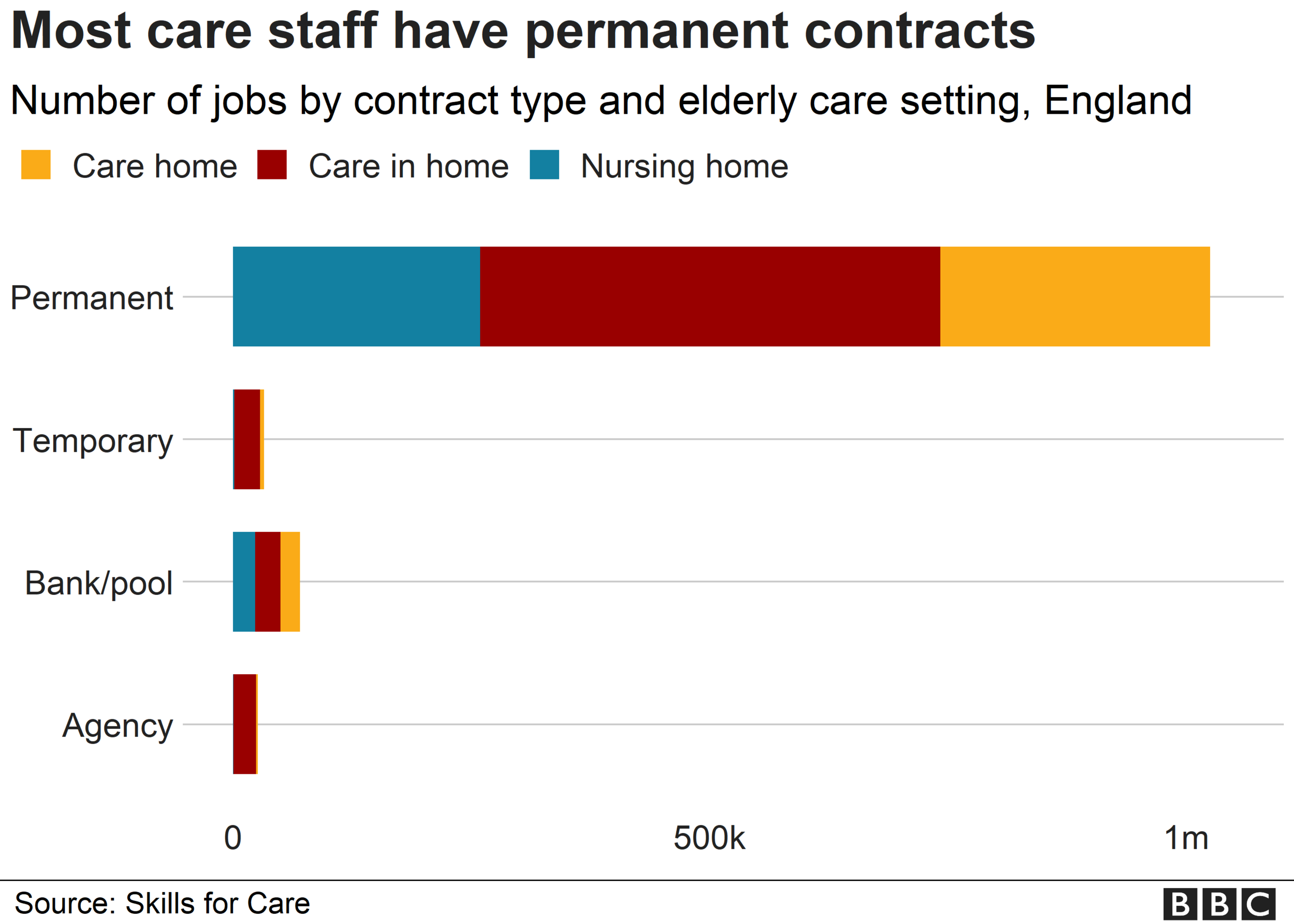

In England, there are 112,000 vacancies and the sector relies heavily on agency staff, who tend to be paid more.

The high number of deaths in care homes meant many care workers faced losing people they looked after on a scale for which no-one could have been prepared.

To minimise the spread of the virus, many GPs and community nurses stopped visiting homes, so were only available on the phone. Fewer residents were admitted to hospital when they fell ill.

It meant care staff had to take on increased responsibilities for the health and care of their residents.

The work of care staff is better recognised now, but the fundamental problems of low pay and difficulties retaining and recruiting people remain.

Some money from a £1.1bn infection control fund has been used to ensure care staff get sick pay if they self-isolate.

The number of agency staff working in different homes has been reduced.

The government is said to be planning legislation which will ban the movement of staff between homes. It's not clear how this will work in practice.

Money problems remain

An ageing population and a decade of austerity means that social care has been underfunded and widely viewed as in crisis for some time.

In England, fewer people get support with day-to-day living from local authorities than in 2010.

People who fund themselves are often propping up the system by paying more for the same care as those funded by councils.

During the pandemic, the government has given:

£3.2bn to local authorities for front-line services, including social care

£1.1bn "infection control money" for care homes

However, increased costs from PPE, infection control measures and additional staffing have combined with a fall in the number of people moving into care homes.

Many of the problems remain.

A recent report by the Health and Social Care Select Committee said: "The crisis in social care funding has been brought into sharp focus by the Covid-19 pandemic."

It called for an additional £3.9bn annual funding by 2023-24 just to keep up with increased demand and to meet planned rises in the National Living Wage.

On his first day as prime minister, Boris Johnson promised to "fix the social care system once and for all".

He has since repeated his pledge of longer-term reform on several occasions, but details have yet to be published.