AstraZeneca vaccine: Did nationalism spoil UK's 'gift to the world'?

- Published

The Oxford-AstraZeneca vaccine was a British success story - a home-grown vaccine developed and rolled out in less than 12 months. The ambition was huge: to create a vaccine for the world. But did politics and nationalism get in the way?

In the UK, nearly half the adult population has received two doses of AstraZeneca's Covid-19 vaccine. It seems highly likely to have saved more lives here to date than the Pfizer and Moderna jabs combined. Yet it is now barely used by the National Health Service. More than 37 million people have received a booster dose in the UK. Just 48,000 of those were AstraZeneca.

The vaccine has also been sidelined in the EU and was never approved in the United States.

So how did we end up here? I've been talking to scientists, politicians and commentators about the fate of the Oxford-AstraZeneca vaccine, billed by ministers as "Britain's gift to the world", for a documentary on BBC Two.

I've been asking one central question: did politics and national interests get in the way of ambitions for the vaccine?

Sir John Bell, Regius professor at Oxford University and a man at the heart of the team that got the Oxford vaccine out of the lab and into the arms of millions, is highly critical about decision-makers in the EU.

"They have damaged the reputation of the vaccine in a way that echoes around the rest of the world," he told us. "I think bad behaviour from scientists and from politicians has probably killed hundreds of thousands of people - and that they cannot be proud of."

"Bad behaviour by politicians has probably killed hundreds of thousands of people" - Prof Sir John Bell

Let's go back to early 2021. The Alpha variant was driving up Covid hospital admissions and deaths, putting huge pressure on the UK's health service.

Yet it was also a time of hope. The UK had begun to roll out the highly effective Pfizer and AstraZeneca vaccines - which it had approved here before anywhere else in the world.

The Oxford-AstraZeneca jab was celebrated as a home-grown success story - reflecting the strength of UK biosciences and academia. The government had even looked at the possibility of putting the union flag on the side of the vaccine.

But the scientists at Oxford were uncomfortable with any hint of trumpeting Britishness - by its very nature, a pandemic does not respect borders. The scientists' aim was to tackle the spread of the virus around the world, and prevent new mutations from cropping up in unprotected countries.

"There was too much nationalism," says Prof Adrian Hill, director of the Jenner Institute in Oxford, where the vaccine was developed. "It was encouraging competition between vaccine types, between countries. That's the last thing you want in trying to control the pandemic and provide vaccines for the world."

The vaccine's approval in the UK coincided with Britain's formal separation from the EU.

"I don't think it made relations with Europe any easier that it was promoted as the British vaccine," says Sir John Bell.

In the UK, despite the terrible toll of Covid, there was a buoyant atmosphere in every vaccine centre I attended.

By contrast, the mood on mainland Europe was sombre.

"What we couldn't understand is that while we were deprived of vaccines, we heard that the UK was vaccinating non-stop," says Dr Veronique Trillet-Lenoir, of the European Parliament's Vaccine Contact Group.

By late January, the EU, whose vaccine rollout was lagging behind the UK, finally looked set to approve AstraZeneca.

But before European regulators made their decision, Germany decided it should not be given to those over 65., external While in France, President Macron, called the vaccine "quasi-ineffective" in the elderly, external.

But just hours later, the European Medicines Agency approved the jab for adults of all ages.

Both Germany and France would reverse their decisions, but the reputation of the vaccine had been damaged. Some doctors in France had to throw away doses because nobody was turning up to get the jab.

When France restarted using the vaccine, its prime minister, Jean Castex, received the AZ jab live on TV in a bid to restore public confidence

So how could this have happened? It is complicated, so bear with me.

The AstraZeneca - or AZ for short - vaccine was approved in the UK and EU for older adults before firm evidence showing it protected them from Covid. The trials demonstrated it protected younger volunteers. But the older adults had been recruited later. Their blood samples showed the vaccine produced a very strong immune response to coronavirus - just as it did in younger volunteers.

So an assumption was made that it would protect the elderly just as well as younger people. This turned out to be correct. In the midst of a pandemic, with vaccines desperately needed, regulators decided to approve the jab for older adults, who were most at risk from Covid. But France and Germany were more cautious.

On the same day as the French prime minister, Boris Johnson received his first dose of AstraZeneca in London

At the same time, AZ was becoming embroiled in a major row about supplies. Its Covid vaccine was being manufactured in both the UK and the EU. Because the UK had been guaranteed priority in a deal agreed before the rest of Europe, the company says it was unable to send vaccines from British plants to supplement the EU stock. Meanwhile, one million doses had already gone to the UK from an EU plant.

At the height of the crisis, the European Commission threatened to halt vaccine exports to the UK, external unless Europe got its "fair share".

But what sealed the vaccine's poor reputation among many across Europe was the emergence in March of a link to rare blood clots. Germany, France, Ireland, Italy, Austria and Denmark were among many nations that suspended use of the vaccine.

The overall risk of blood clots is very low - estimated at one in 65,000 overall - but slightly higher in younger adults. When European regulators declared that the vaccine's benefits outweighed its risks, most lifted their suspension - but put age restrictions on the vaccine.

In the UK public confidence and pride in the vaccine remained high, even after the jab was restricted to over-40s because of the link to rare blood clots.

But when it came to deciding on booster doses in the UK, the clots issue and the simplicity of the Pfizer or Moderna mRNA jabs not being age-restricted, sealed the AZ vaccine's fate. It is registered as a booster vaccine here, but it proved simpler to give the majority of people Pfizer or Moderna - even though this was a far more expensive option. Since then, evidence has shown that mixing different types of vaccine may offer better protection.

Elsewhere in Europe many saw the AZ vaccine as either unsafe or inferior - it was nicknamed the "Aldi vaccine" in Belgium, after the supermarket, because it was seen as a budget option.

But it had been designed to be cheap. Its developers had had the ambition that it should be available at low cost, throughout the world. Unlike the mRNA vaccines it could be transported and stored at fridge temperature, making it easier to administer in remote regions.

AZ agreed to license global production and distribution of the jab, to be sold not-for-profit, for about £3 a dose - a fifth of the price of the Pfizer's jab.

A key player in this deal was the Serum Institute in India, the world's largest manufacturer of vaccines. It agreed to produce more than one billion doses for low- and middle-income countries. But when the devastating Delta wave of Covid struck India in spring 2021, its government blocked vaccines leaving the country, external for more than six months, making a global shortage of vaccines even more acute.

A woman reading a poster saying "vaccine out of stock" outside a vaccination centre in Mumbai in April 2021

"Once India shut that door…the sense was we are truly well and truly done for because at that point, that was the only hope," says Dr Ayoade Alakija of the African Union Vaccine Delivery Alliance.

The difference between rich and poor countries was extreme. In September 2021, when the UK, US, France and others were starting to offer booster doses, just one in 100 people in low income countries had been double-jabbed.

"By the time you got through the first half of 2021, enough doses have been manufactured that could have prevented almost all of the deaths in the second half of 2021 - if those doses had been targeted at older adults, those with health conditions and healthcare workers all over the world," Prof Andrew Pollard from the Oxford Vaccine Group told us.

"We haven't got it right. But how do you make politicians comfortable with the moral imperative that there should be in a pandemic?"

Global vaccine rollout

Global vaccine rollout

Percent of people fully vaccinated

| World |

61

|

12,120,524,547 |

| China |

87

|

3,403,643,000 |

| India |

66

|

1,978,918,170 |

| US |

67

|

596,233,489 |

| Brazil |

79

|

456,903,089 |

| Indonesia |

61

|

417,522,347 |

| Japan |

81

|

285,756,540 |

| Bangladesh |

72

|

278,785,812 |

| Pakistan |

57

|

273,365,003 |

| Vietnam |

83

|

233,534,502 |

| Mexico |

61

|

209,179,257 |

| Germany |

76

|

182,926,984 |

| Russia |

51

|

168,992,435 |

| Philippines |

64

|

153,852,751 |

| Iran |

68

|

149,957,751 |

| UK |

73

|

149,397,250 |

| Turkey |

62

|

147,839,557 |

| France |

78

|

146,197,822 |

| Thailand |

76

|

139,099,244 |

| Italy |

79

|

138,319,018 |

| South Korea |

87

|

126,015,059 |

| Argentina |

82

|

106,075,760 |

| Spain |

87

|

95,153,556 |

| Egypt |

36

|

91,447,330 |

| Canada |

83

|

86,256,122 |

| Colombia |

71

|

85,767,160 |

| Peru |

83

|

77,892,776 |

| Malaysia |

83

|

71,272,417 |

| Saudi Arabia |

71

|

66,700,629 |

| Myanmar |

49

|

62,259,560 |

| Chile |

92

|

59,605,701 |

| Taiwan |

82

|

58,215,158 |

| Australia |

84

|

57,927,802 |

| Uzbekistan |

46

|

55,782,994 |

| Morocco |

63

|

54,846,507 |

| Poland |

60

|

54,605,119 |

| Nigeria |

10

|

50,619,238 |

| Ethiopia |

32

|

49,687,694 |

| Nepal |

69

|

46,888,075 |

| Cambodia |

85

|

40,956,960 |

| Sri Lanka |

68

|

39,586,599 |

| Cuba |

88

|

38,725,766 |

| Venezuela |

50

|

37,860,994 |

| South Africa |

32

|

36,861,626 |

| Ecuador |

78

|

35,827,364 |

| Netherlands |

70

|

33,326,378 |

| Ukraine |

35

|

31,668,577 |

| Mozambique |

44

|

31,616,078 |

| Belgium |

79

|

25,672,563 |

| United Arab Emirates |

98

|

24,922,054 |

| Portugal |

87

|

24,616,852 |

| Rwanda |

65

|

22,715,578 |

| Sweden |

75

|

22,674,504 |

| Uganda |

24

|

21,756,456 |

| Greece |

74

|

21,111,318 |

| Kazakhstan |

49

|

20,918,681 |

| Angola |

21

|

20,397,115 |

| Ghana |

23

|

18,643,437 |

| Iraq |

18

|

18,636,865 |

| Kenya |

17

|

18,535,975 |

| Austria |

73

|

18,418,001 |

| Israel |

66

|

18,190,799 |

| Guatemala |

35

|

17,957,760 |

| Hong Kong |

86

|

17,731,631 |

| Czech Republic |

64

|

17,676,269 |

| Romania |

42

|

16,827,486 |

| Hungary |

64

|

16,530,488 |

| Dominican Republic |

55

|

15,784,815 |

| Switzerland |

69

|

15,759,752 |

| Algeria |

15

|

15,205,854 |

| Honduras |

53

|

14,444,316 |

| Singapore |

92

|

14,225,122 |

| Bolivia |

51

|

13,892,966 |

| Tajikistan |

52

|

13,782,905 |

| Azerbaijan |

47

|

13,772,531 |

| Denmark |

82

|

13,227,724 |

| Belarus |

67

|

13,206,203 |

| Tunisia |

53

|

13,192,714 |

| Ivory Coast |

20

|

12,753,769 |

| Finland |

78

|

12,168,388 |

| Zimbabwe |

31

|

12,006,503 |

| Nicaragua |

82

|

11,441,278 |

| Norway |

74

|

11,413,904 |

| New Zealand |

80

|

11,165,408 |

| Costa Rica |

81

|

11,017,624 |

| Ireland |

81

|

10,984,032 |

| El Salvador |

66

|

10,958,940 |

| Laos |

69

|

10,894,482 |

| Jordan |

44

|

10,007,983 |

| Paraguay |

48

|

8,952,310 |

| Tanzania |

7

|

8,837,371 |

| Uruguay |

83

|

8,682,129 |

| Serbia |

48

|

8,534,688 |

| Panama |

71

|

8,366,229 |

| Sudan |

10

|

8,179,010 |

| Kuwait |

77

|

8,120,613 |

| Zambia |

24

|

7,199,179 |

| Turkmenistan |

48

|

7,140,000 |

| Slovakia |

51

|

7,076,057 |

| Oman |

58

|

7,068,002 |

| Qatar |

90

|

6,981,756 |

| Afghanistan |

13

|

6,445,359 |

| Guinea |

20

|

6,329,141 |

| Lebanon |

35

|

5,673,326 |

| Mongolia |

65

|

5,492,919 |

| Croatia |

55

|

5,258,768 |

| Lithuania |

70

|

4,489,177 |

| Bulgaria |

30

|

4,413,874 |

| Syria |

10

|

4,232,490 |

| Palestinian Territories |

34

|

3,734,270 |

| Benin |

22

|

3,681,560 |

| Libya |

17

|

3,579,762 |

| Niger |

10

|

3,530,154 |

| DR Congo |

2

|

3,514,480 |

| Sierra Leone |

23

|

3,493,386 |

| Bahrain |

70

|

3,455,214 |

| Togo |

18

|

3,290,821 |

| Kyrgyzstan |

20

|

3,154,348 |

| Somalia |

10

|

3,143,630 |

| Slovenia |

59

|

2,996,484 |

| Burkina Faso |

7

|

2,947,625 |

| Albania |

43

|

2,906,126 |

| Georgia |

32

|

2,902,085 |

| Latvia |

70

|

2,893,861 |

| Mauritania |

28

|

2,872,677 |

| Botswana |

63

|

2,730,607 |

| Liberia |

41

|

2,716,330 |

| Mauritius |

74

|

2,559,789 |

| Senegal |

6

|

2,523,856 |

| Mali |

6

|

2,406,986 |

| Madagascar |

4

|

2,369,775 |

| Chad |

12

|

2,356,138 |

| Malawi |

8

|

2,166,402 |

| Moldova |

26

|

2,165,600 |

| Armenia |

33

|

2,150,112 |

| Estonia |

64

|

1,993,944 |

| Bosnia and Herzegovina |

26

|

1,924,950 |

| Bhutan |

86

|

1,910,077 |

| North Macedonia |

40

|

1,850,145 |

| Cameroon |

4

|

1,838,907 |

| Kosovo |

46

|

1,830,809 |

| Cyprus |

72

|

1,788,761 |

| Timor-Leste |

52

|

1,638,158 |

| Fiji |

70

|

1,609,748 |

| Trinidad and Tobago |

51

|

1,574,574 |

| Jamaica |

24

|

1,459,394 |

| Macau |

89

|

1,441,062 |

| Malta |

91

|

1,317,628 |

| Luxembourg |

73

|

1,304,777 |

| South Sudan |

10

|

1,226,772 |

| Central African Republic |

22

|

1,217,399 |

| Brunei |

97

|

1,173,118 |

| Guyana |

58

|

1,011,150 |

| Maldives |

71

|

945,036 |

| Lesotho |

34

|

933,825 |

| Yemen |

1

|

864,544 |

| Congo |

12

|

831,318 |

| Namibia |

16

|

825,518 |

| Gambia |

14

|

812,811 |

| Iceland |

79

|

805,469 |

| Cape Verde |

55

|

773,810 |

| Montenegro |

45

|

675,285 |

| Comoros |

34

|

642,320 |

| Papua New Guinea |

3

|

615,156 |

| Guinea-Bissau |

17

|

572,954 |

| Gabon |

11

|

567,575 |

| Eswatini |

29

|

535,393 |

| Suriname |

40

|

505,699 |

| Samoa |

99

|

494,684 |

| Belize |

53

|

489,508 |

| Equatorial Guinea |

14

|

484,554 |

| Solomon Islands |

25

|

463,637 |

| Haiti |

1

|

342,724 |

| Bahamas |

40

|

340,866 |

| Barbados |

53

|

316,212 |

| Vanuatu |

40

|

309,433 |

| Tonga |

91

|

242,634 |

| Jersey |

80

|

236,026 |

| Djibouti |

16

|

222,387 |

| Seychelles |

82

|

221,597 |

| Sao Tome and Principe |

44

|

218,850 |

| Isle of Man |

79

|

189,994 |

| Guernsey |

81

|

157,161 |

| Andorra |

69

|

153,383 |

| Kiribati |

50

|

147,497 |

| Cayman Islands |

90

|

145,906 |

| Bermuda |

77

|

131,612 |

| Antigua and Barbuda |

63

|

126,122 |

| Saint Lucia |

29

|

121,513 |

| Gibraltar |

123

|

119,855 |

| Faroe Islands |

83

|

103,894 |

| Grenada |

34

|

89,147 |

| Greenland |

68

|

79,745 |

| St Vincent and the Grenadines |

28

|

71,501 |

| Liechtenstein |

69

|

70,780 |

| Turks and Caicos Islands |

76

|

69,803 |

| San Marino |

69

|

69,338 |

| Dominica |

42

|

66,992 |

| Monaco |

65

|

65,140 |

| Saint Kitts and Nevis |

49

|

60,467 |

| British Virgin Islands |

59

|

41,198 |

| Cook Islands |

84

|

39,780 |

| Anguilla |

67

|

23,926 |

| Nauru |

79

|

22,976 |

| Burundi |

0.12

|

17,139 |

| Tuvalu |

52

|

12,528 |

| Saint Helena |

58

|

7,892 |

| Montserrat |

38

|

4,422 |

| Falkland Islands |

50

|

4,407 |

| Niue |

88

|

4,161 |

| Tokelau |

71

|

1,936 |

| Pitcairn |

100

|

94 |

| British Indian Ocean Territory |

0

|

0 |

| Eritrea |

0

|

0 |

| North Korea |

0

|

0 |

| South Georgia and the South Sandwich Islands |

0

|

0 |

| Vatican |

0

|

0 |

Please upgrade your browser to see the full interactive

This information is regularly updated but may not reflect the latest totals or vaccines administered for each location. Total doses may include booster doses in addition to those required for full vaccination. The definition of full vaccination varies by location and vaccine type and is subject to change over time. Full vaccination can refer to a person receiving all required doses of a specific vaccine or sometimes recovery from infection plus one dose of a vaccine. Definitions have not yet been updated to account for booster campaigns to control the spread of new variants. Some locations may reach vaccination rates over 100%, such as Gibraltar, due to population estimates that are lower than the number of people who have now been vaccinated in that place.

Source: Our World in Data

Last updated: 5 July 2022, 13:28 BST

Dr Bruce Aylward of the World Health Organization is scathing about what he regards as the failure of the world to distribute vaccines fairly.

"We're giving this virus the opportunity to evolve, to mutate, to present in more rapidly transmissible or deadly forms. We're going to be deep into 2022 before we have this pandemic under control, because that's how long it's going to take to get vaccines rolled out equitably around the world."

The UK government, which invested £88m in the vaccine's development, has so far donated 30m doses of AZ as part of its commitment to give away 100m Covid vaccines overall. The first UK donations did not happen until late July 2021.

The former health secretary Matt Hancock said the UK's main contribution was giving the science and wherewithal for others globally to produce the jab. "Give a man the tools and teach them how to fish. And that is far more powerful in terms of saving lives than any number of vaccines we could have manufactured here and then physically exported on an aeroplane."

In recent months, global supplies and promises of vaccine donations have increased significantly. But millions of donated doses have only weeks left before they expire, and not all can be used in time. There is also the issue of vaccine hesitancy which is a significant hurdle in many parts of the world.

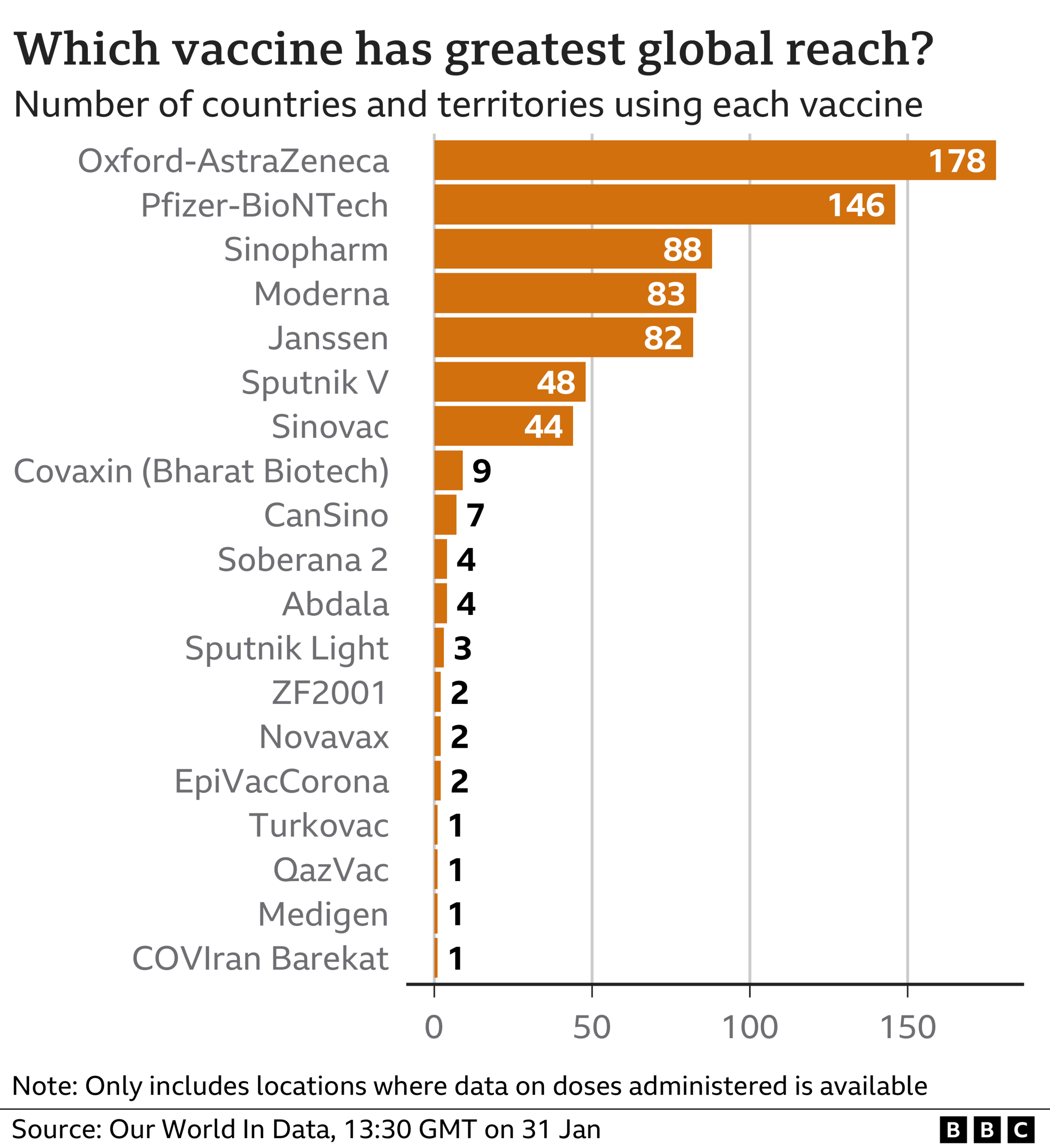

Despite all the problems, more than 2.5 billion doses of the Oxford-AstraZeneca jab have been delivered to 183 nations, nearly two-thirds to low and middle-income countries. It will continue to be sold at cost to developing nations while the company says it will make a "modest profit" elsewhere. It is impossible to calculate how many lives have been saved by the vaccine, but the company estimates it to be more than a million.

More than a quarter of the 10 billion doses of Covid jabs administered globally have been AstraZeneca, a vaccine created by a small team at a British university and sold at cost. Other Covid vaccines, by contrast, have created nine billionaires.

Despite the public relations mauling that AstraZeneca has received in Europe and the US over the vaccine, the company's chief executive, Pascal Soriot, said he'd pursue the non-profit route again in a future pandemic. But he was candid about the issues surrounding vaccine equity, and the muscular way wealthier nations snapped up doses before poorer ones.

"You can't change human beings," he said. "They are going to take care of themselves and their families first, their neighbours second and the rest of the world third. You would have hoped that export bans didn't exist and vaccines flowed across the world much more freely, but you just have to accept the reality."

Watch AstraZeneca: A Vaccine for the World? on BBC Two Tuesday 8 February at 21:00, or later on the BBC iPlayer (UK only).