Life after vaginal mesh surgery

- Published

The health watchdog has suggested controversial vaginal mesh implants should be offered again on the NHS. Use of vaginal mesh was halted across the UK last year amid safety concerns.

But, on Tuesday, the National Institute for Health and Care Excellence said the "limited evidence" meant "the true prevalence of long-term complications following surgery with mesh is unknown".

Here, Caroline Briggs talks to some of the women who say their lives were radically changed by the procedure.

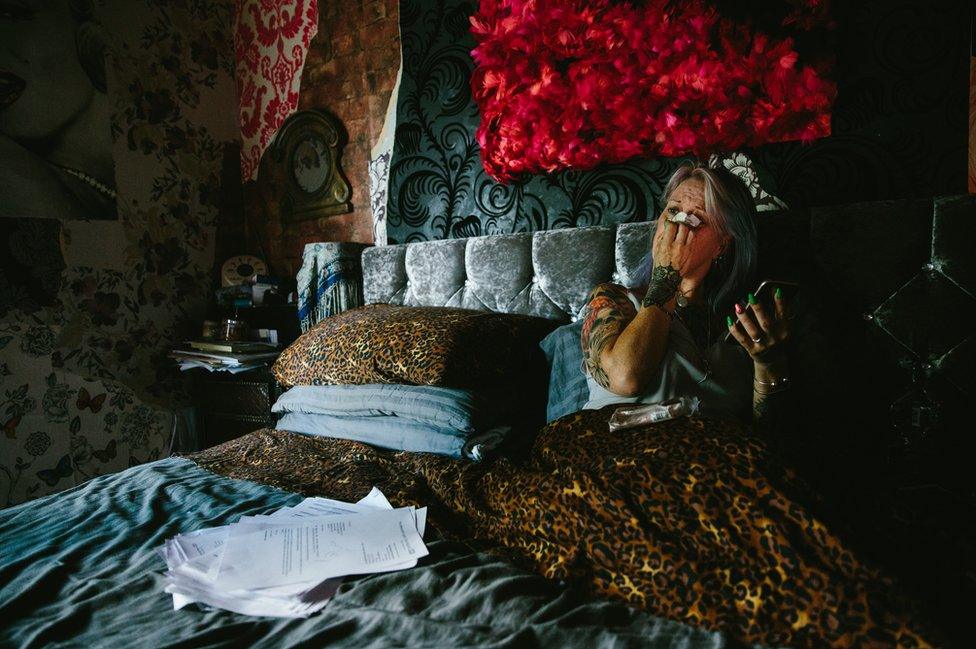

Mel Semple lives in Newcastle with her husband, Ronnie, her three youngest children, and three dogs.

As a result of childbirth, Mel experienced mild incontinence, limited to when she was coughing or sneezing, and was fitted with vaginal mesh on the advice of a doctor.

The incontinence had been nothing more a nuisance, a disorder common to millions of women following childbirth.

It did not dominate or dictate her lifestyle - but, within weeks of the procedure, that would change.

Mel stopped being the active, healthy mother her family knew, and became a mass of pain, exhausted by the slightest effort.

Before long, her day-to-day life had become dominated by the simplest functions of her body.

Her incontinence became worse and she felt at constant risk of wetting herself.

As a drastic measure, she started to limit her fluid intake - and began to develop bladder infections, for the first time in her life.

One was so severe that she was admitted to hospital.

Today, Mel has to measure every journey by the distance to the nearest toilet.

It means she often finds it easier to stay at home - and her life has become more isolated.

On those days where she does venture out, she has to limit what she can drink.

A hot tub in the back garden provides relief from the constant pains in her hips and pelvis and from the fibromyalgia with which she was recently diagnosed.

A survey by the Sling The Mesh campaign group suggests a third of women fitted with vaginal mesh now have this debilitating condition - way above the national average.

Pressing surgeons for an operation to reverse the procedure, Mel spent most of the summer confined to her bed, unable to leave the house.

To get the go-ahead for the operation, she had to endure numerous visits to hospital for a series of scans and tests. Many are invasive, some are humiliating.

A Tens machine - often used by women in labour - provides some relief from the constant pain in her hips.

Family life has been placed under strain.

When her children were small, their lives were spent outdoors - cycling, walking and enjoying long adventures in the countryside.

Today, Mel's daughter is surprised when her mother is well enough to get out of bed.

Prescribed with powerful painkillers, such as Gabapentin and Pregabalin - drugs sometimes used by cancer patients, Mel has long been used to a daily intake of pills.

But the side-effects are "horrendous".

Instead, she has turned to alternatives such as cannabis oil in an attempt to manage her chronic pain.

Mel lives for her "better" days, when the pain subsides and her "brain fog" lifts.

On these days, Mel is able to get out of bed and tries her best to lead a normal life.

But her health and regular hospital appointments have come to dominate her existence, as she struggles to manage her condition and to be a mother to her children.

Jackie Cheetham, from Pickering, North Yorkshire, lives every day of her life in agonising pain.

This pain - like "being cut inside by a cheese wire" - began in 2006, shortly after she was fitted with vaginal mesh as part of a surgical treatment for incontinence.

For months, doctors dismissed her pain as psychosomatic - and she attempted to take her own life.

One in 20 women who responded to a recent survey by the Sling The Mesh campaign group said they had attempted suicide, with many more having suicidal thoughts.

After nearly 13 years, Jackie is unable to walk long distances - or to sit for any length of time.

She relies on a stick daily - and has to use a mobility scooter for long journeys.

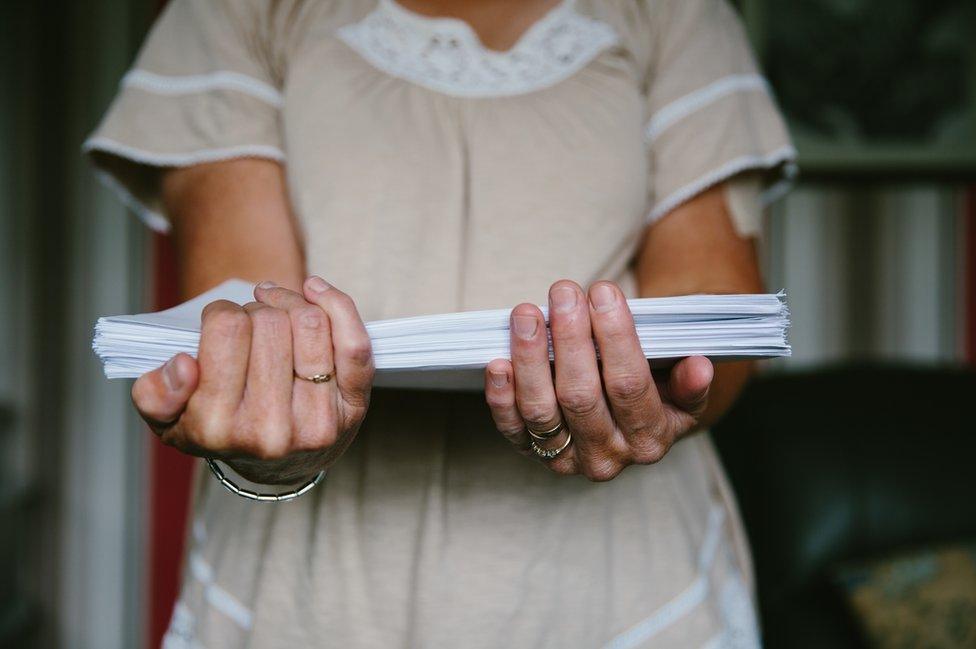

The correspondence relating to her case runs to hundreds of pages.

In over a decade of discussion between health professionals, Jackie says her GP has been the only one who has consistently fought her corner.

Doctors initially told her mesh complications were one in a million, she says.

Others refused to believe the extent of her suffering.

And some even advocated that she should be sectioned under the Mental Health Act.

Her children are now grown up but they spent their childhood concerned every day for their mother's mental and physical wellbeing.

Jackie believes the experience has had a long-lasting effect on them.

Gill Hedley, from Newcastle, had mesh fitted in a procedure called a rectopexy, following a bowel prolapse.

She says the side-effects left her unable to work and she had to give up her house.

Gill's mesh was eventually removed but in doing so the surgeon had to remove Gill's rectum and part of her intestine.

She has been left with a permanent stoma and faces more surgery to close the incision wound, still open two years after the initial operation.

It has to be packed and dressed three times each week.

Gill says the problems caused by her mesh have had a profound and damaging effect on her mental health.

Kath Sansom, a journalist from Cambridgeshire, was a keen mountain biker and high board diver.

Four years ago, she had mesh surgery following the birth of her youngest child.

Within weeks, she says, an intense burning sensation in her vagina and severe leg pains left her "a wreck".

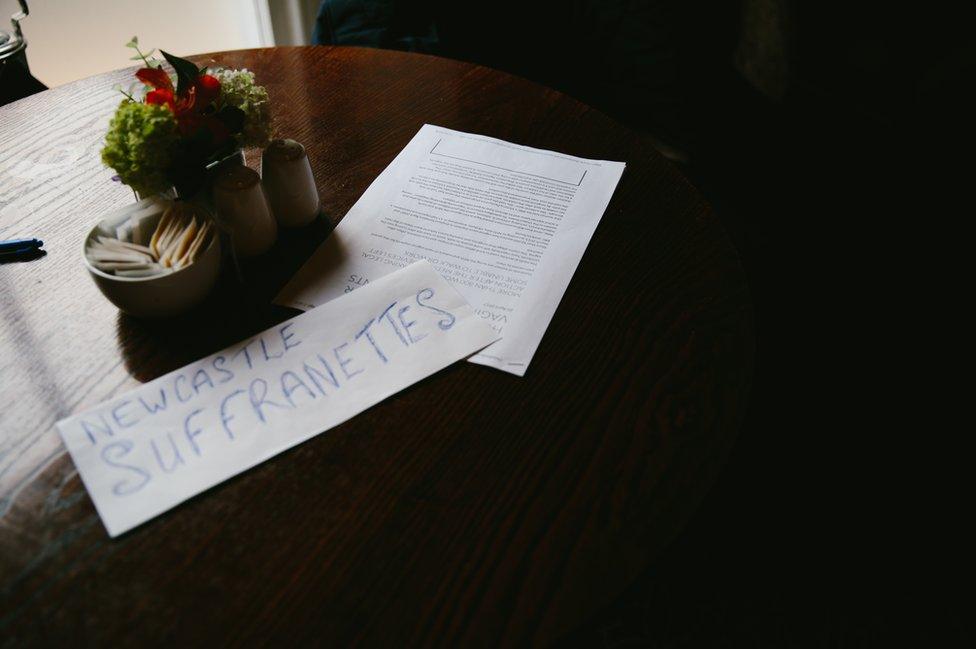

Kath founded the campaign group Sling The Mesh in 2015, after she discovered that women from across the world had experienced similar problems.

Every week, many more contact her with their stories. The campaign's Facebook group now has more than 7,300 members.

Kath runs the operation from her living room, often working late into the night.

Members' stories frequently reduce her to tears.

Photos and text by Caroline Briggs