Want more on climate? The BBC has you coveredpublished at 16:34 GMT 24 November 2024

Malu Cursino

Malu Cursino

Live page editor

Here is the moment the climate cash deal was gavelled through more than 32 hours after the conference was due to end, as my colleague Jack Burgess has been providing all the updates from Azerbaijan's capital, Baku. If you want more on COP29, we have you covered.

COP29: Standing ovation as long awaited climate finance deal is agreed

Key takeaways from COP29: Now that climate talks in Baku have wrapped up my colleague, environment correspondent Matt McGrath, looks at the take home messages from COP29 from re-opened feuds between rich and poor to the host country's role in negotiations.

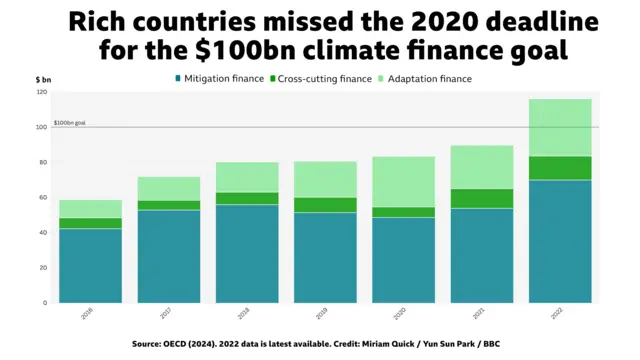

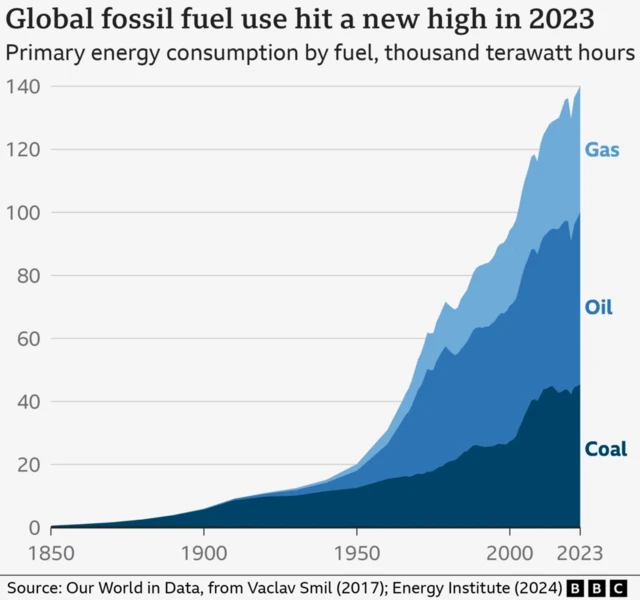

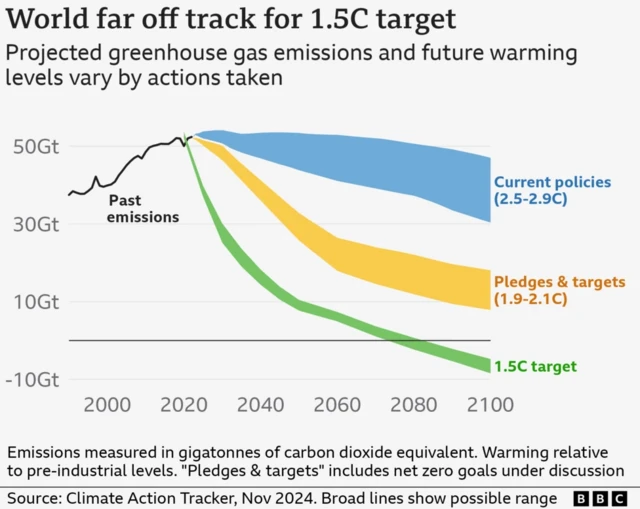

Are we doing enough? Scientists, politicians and world leaders met at the annual UN climate conference in Baku in what's set to be the hottest year on record. The BBC's Mark Poynting and Georgina Rannard look at what progress countries have already made to tackle climate change.

Impact of US elections on climate talks in Baku: The BBC's climate editor Justin Rowlatt looks at whether China will step up in the climate space with the prospect of US president-elect Donald Trump withdrawing the US from the COP process when he takes office for a second time looming over.

Listen: In their latest episode the Climate Question looks at how climate change affects our everyday lives - from prices at supermarket to where we go on holiday.

We're now ending our live coverage, thank you for following along with us in the moments leading up to the deal, and during the criticism in the aftermath today. For now, you can keep up to date with the latest from our colleagues on the news desk.

Image source, Tony Jolliffe / BBC

Image source, Tony Jolliffe / BBC