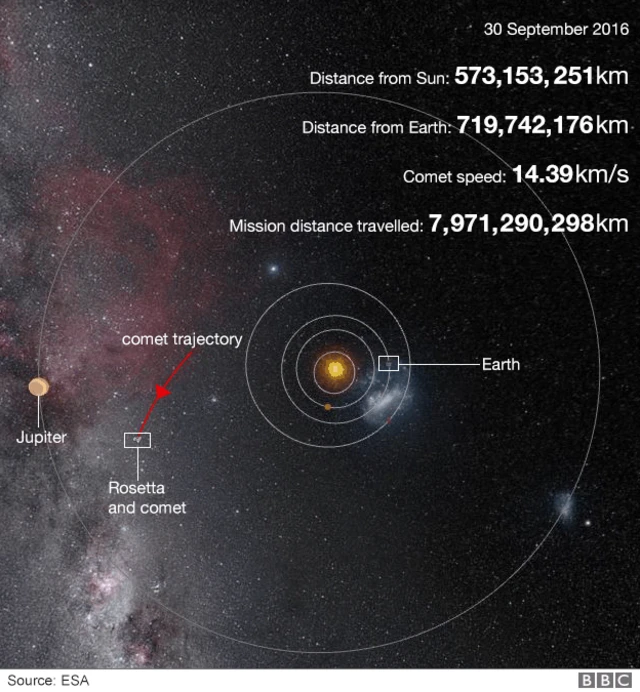

Where is Rosetta and how far has the craft travelled?published at 10:18 BST 30 September 2016

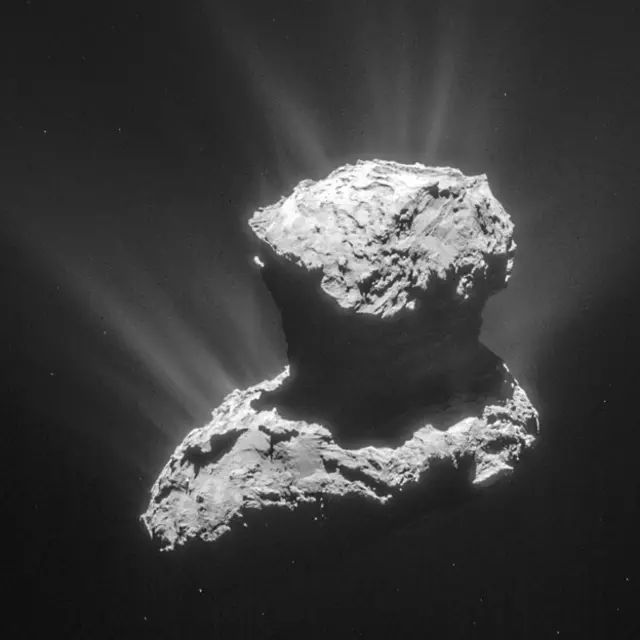

The spacecraft and the comet are heading out towards Jupiter. Light falling on its solar panels is diminishing to the point where it will no longer be able to operate all its instruments