Mafia cast shadow over Sicily even as properties seized

- Published

Remote usually means relaxing when choosing a spot for a family holiday - but when your bed and breakfast was previously owned by a Sicilian Mafia boss, the charm of isolation can begin to fade.

Salvatore Riina, otherwise known as The Beast, personally ordered the murders of magistrates, policemen and scores of rivals throughout two decades. He was finally captured near Palermo in May 1993 after 23 years on the run.

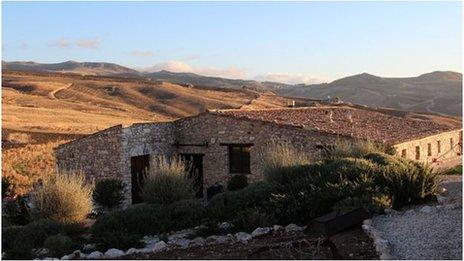

As you drive down the wheel-spinningly steep gravel path to his country home in the hillsides surrounding Corleone, you have the sense of being swallowed by the landscape.

Invisible from the main road high above, the low stone building sits nestled in a fold of undulating pasture.

Rumours that Mr Riina hid here to evade capture have never been confirmed but his family certainly worked on this farmland until the Italian government seized the property under a law passed in 1996.

Salvatore Riina is thought to have personally killed 40 men

It was then transferred to a co-operative that over the past decade has been steadily transforming repossessed former Mafia haunts into ethical ("Mafia-free") businesses - organic wine and food production, guesthouses and restaurants

It was definitely a little disconcerting, on our first night, to find we were the only guests… and that there was no phone signal.

But the restaurant attached to the farmhouse was open for business and a hearty Sicilian meal settled our nerves, as did the young mum on overnight duty that evening. "Ten years ago, there was no way I would have slept in this place alone" said Fabiana. "But I don't even give it a second thought now."

Right now, the notorious Riina family has more on its plate than tourists eating in their former stables. This summer, 79-year-old Gaetano Riina, alleged to have been the clan's cashier, was arrested along with three younger family members.

Local people do seem reluctant, though, to visit the farmhouse despite the good-value food on offer.

The clients mostly come from further afield, customers of a new brand of Sicilian travel agency offering Mafia-free holidays at establishments that refuse to pay protection money, or "pizzo".

Shuttered windows

Corleone is still home to powerful Mafia families

A group of 50 teenagers from a college in Bologna filled the restaurant one lunchtime with excited chatter. "It's a victory over the Mafia that we're here to eat at this table," said 18-year-old Cristiana.

But the Sicilian Mafia, or Cosa Nostra, are ever-present. "We all still know who the local bosses are right now," says one local. "They're just not the brutal gangster types of the olden days."

Five miles up the road is the town of Corleone. Tourists often pose alongside the sign, not realising that the famous Godfather films were actually filmed elsewhere in Sicily. Judging by the numbers of shop windows displaying bottles of Il Padrino wine, local businesses are happy to exploit the town's on-screen association with violence.

Corleone, though, is still home to powerful Mafia families. There are no visible clues to the wealth that is said to lie behind the firmly shuttered doors and windows of its narrow streets.

Yet right in the heart of the town, another jailed Mafia boss's home has been radically transformed. Bernardo Provenzano, dubbed The Tractor for his ruthless trait of mowing people down, was arrested and jailed in 2006. Now the giant sign outside his front door says "Bottega della Legalita" or "Shop of Legality".

The ground floor is a shop selling pasta, sauces and wine produced by co-operatives now farming former Mafia land. The shelves were sparsely stocked and there was a distinct lack of customers, I noticed.

"That's because it's absolutely impossible to shop here unseen," explained shop manager Liborio Grizzaffi, gesturing through the open door to the street. Apparently one of Provenzano's relatives still owns the house opposite.

"The older generation is still fearful. But the very fact we are here in Provenzano's family home would have been unthinkable a decade ago. Actually some housewives are now realising that our pasta sauce is really rather good."

Ethical wine

Above the shop is an exhibition that aims to change perceptions of Mafia culture among younger generations.

Particularly disturbing is the tribute to murdered children, including one 11-year-old boy, kidnapped, strangled, and then dissolved in acid. There are also portraits of men and women who bravely fought against the Mafia. Most met unhappy endings.

Most Mafia-free wine is sold in northern Italy, not Sicily

We turned a corner into a side room showing Mafiosi arrests. And suddenly there he was. Bernardo Provenzano. The building's notorious former owner. Large as life - but fortunately made of cardboard.

There's also a portrait of Giovanni Brusca, a brutal criminal responsible for the kidnap and murder of that poor 11-year-old. The wine sold in the shop downstairs is now produced on Brusca's former vineyards between Corleone and Palermo.

Seven years ago I visited the co-operative setting up legal wine production, external on this land. Back then, locals were reluctant to work there, some reported intimidation and there were several arson attempts.

Today it feels very different. More than 100 people are employed at the Centopassi vineyards, and I saw construction workers building a new visitor centre and tasting room.

"It feels a little bit like a revolution," says manager Stefano Palmero. "People from nearby towns can choose to work here instead of in Mafia-connected firms."

These vineyards produced 300,000 bottles of wine this year. However, most is sold in Northern Italy rather than in Sicily itself.

"Many Sicilian supermarket chains are still run by Mafia interests," explains Lucio Guarino, director of the agency that manages the confiscated land in Sicily.

"We absolutely refuse to deal with them. It sounds mundane but supermarkets are incredibly important now for the Mafia's control over the land and economy."

Breaking the domination of the Mafia in this part of Italy will be a long process.

Transforming confiscated properties into ethical businesses is certainly a start. Already they're attracting tourists and providing employment in tough economic times, and for the younger generations they're a tangible symbol of legality and hope.