Kony2012: The rise of online campaigning

- Published

A social media campaign to shine a light on Ugandan warlord Joseph Kony has attracted ire of its own after critics attacked its methods. Is using Facebook and Twitter to promote change pointless, or the natural extension of our social media habit?

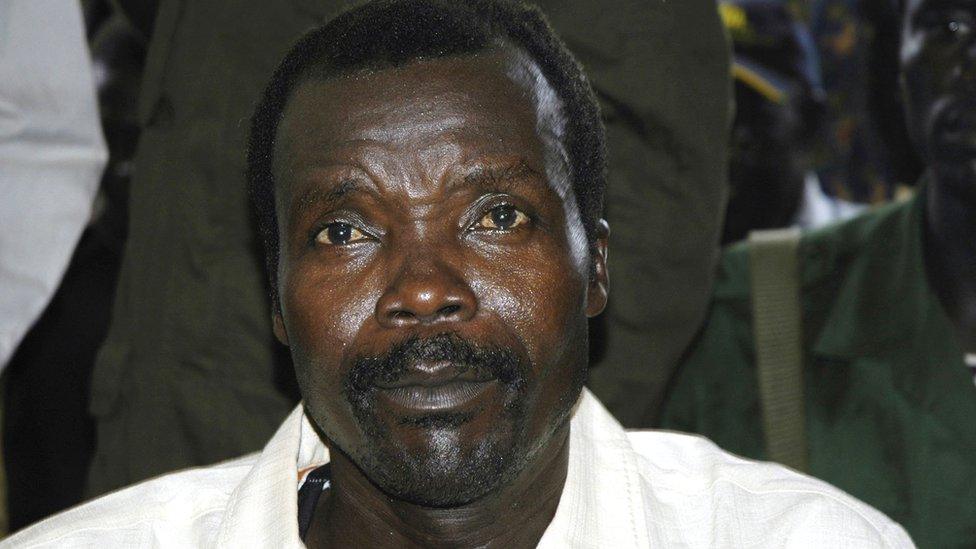

On Monday, the California-based nonprofit Invisible Children released an online 30-minute documentary, external about Joseph Kony, leader of the Lord Resistance Army (LRA). "We want to make him famous," they said. "Not to glorify him, but so that his crimes would not go unnoticed."

It worked.

The video, part of a campaign called Kony2012, became a viral sensation with more than 35 million views. #Kony2012 was a number one topic of conversation on Twitter, and was shared multiple times on Facebook by concerned citizens and celebrities alike.

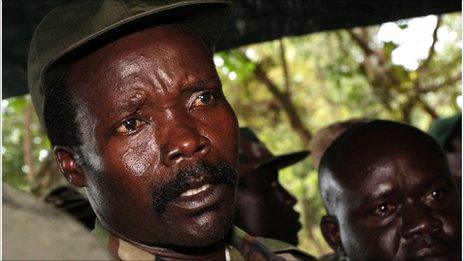

The film also focused on the plight of child soldiers

By Wednesday, there was a shift in mood. Critics pointed out that Invisible Children had a less-than-perfect rating on Charity Navigator, external - an independent charity evaluator based in the US - and questioned the allocation of their funds.

Foreign policy experts and Ugandan nationals noted the situation on the ground was much more complicated than just the crimes of one man. Ugandan journalist Rosebell Kagumire was among those pointing out, external that Invisible Children oversimplified a complicated geopolitical struggle.

Invisible Children posted a response, external to these criticisms on their website.

Most damning were some complaints that the entire campaign reeked of colonialism.

BBC Africa correspondent Andrew Harding described the controversy from the campaign, and called attention to a tweet arguing that "the awareness of American college students is NOT a necessary condition for conflict resolution in Africa".

When it comes to issues like those raised by the Stop Kony campaign, Harding wrote: "The outside world has a role to play, but it is patronising and above all cripplingly counter-productive to believe we have all the answers."

But is colonialism in play, or something much more modern: the idea, however misguided, that the social media generation has the opportunity to change the world with the click of a mouse?

Invisible Children is not shy about its belief in the power of social media. Its documentary claims there are more people on Facebook than were alive 200 years ago. And the charity admits the film is a calculated social media ploy to raise Kony's profile, at one point calling it an "experiment".

It planned - and prepared - for a viral hit and its aftermath.

"The film starts by saying this is a social revolution, and you're part of something special," says Eric Vachon, an account executive for evolve24, a market intelligence company. He says it is a positive lesson for organisations looking to spread their message online.

"They had to help people to make it go viral," he says. This includes calling out specific celebrities and lawmakers to petition and providing the contact info to do so, making follow-up materials easily accessible, and giving the campaign a finite deadline.

For many, the idea that sending tweets and sharing videos on Facebook can solve an international conflict that has stymied world governments is farcical.

But it's an approach not without precedent. From protesting Egyptians in the Arab Spring to those rallying against the Stop Online Piracy Act (SOPA), many have learned their actions online have a certain power.

Just this week, a concerted social media effort led to dozens of companies pulling their advertisements from Rush Limbaugh's radio talkshow after he called a law student a "slut" for advocating for insurance-covered birth control.

There's a big difference, of course, between influencing advertisers and catching a warlord. It's naive to think social media and raised awareness can solve the world's problems.

"Of course it doesn't. But the bigger answer is, the journey starts with a single step," says Amanda Bower, associate professor of marketing at Washington and Lee University. She notes that awareness is required for changing behaviour, and that social media is an extremely effective way to do so.

Riot cleans-up were organised on Twitter

The belief that online activism can change the course of international politics, whether it's arrogant or optimistic, is another hallmark of the social media generation, many of whom consider themselves citizens of a wider online world.

"As these tools become more widespread, there are more people online, which means more people to mobilise and galvanise," says Gerald C Kane, associate professor of information systems at Boston College.

"And as more people participate, more people pay attention," he says.

After all, thanks to the internet, Britons horrified by last summer's riots rallied to clean up their looted streets. And sleuths across the world have connected adopted children and birth parents, and reported crimes from thousands of miles away.

But the Invisible Children campaign may represent the next step in online activism. Previous efforts have been one-sided, with users joining forces against a common foe.

"Now you have two sides going to war in a social media campaign for the public opinion," says Kane.

In the meantime, people are becoming more critical about what they read online, especially when it comes to charitable causes.

"There's definitely a social media fatigue," says Bower. "You can't just put something out there and let it sit. People are going to challenge it."

By Invisible Children's own metrics, though, Kony2012 is already a success.

"Last week, there were millions of people who didn't know who Joseph Kony was, and today they do," says Vachon. "There's value in that."

What value it will have for the people of Uganda, however, is yet to be seen.

- Published8 March 2012

- Published8 March 2012

- Published27 July 2018