The great British fish swap

- Published

- comments

Billingsgate Market is the largest inland fish market in the UK. The original market traded in Lower Thames Street for 900 years, before moving to east London in 1982.

The market is run by the City of London Corporation. Fifty-four licensed merchants trade 25,000 tonnes of fish each year, 40% of which is imported, and its annual turnover is currently estimated to be £200m.

Cod, haddock, plaice, sole and salmon (filleted and ready for sale) as well as shellfish, arrive overnight on lorries from as far afield as Scotland and Cornwall.

Exotic warm water fish such as parrot fish, tilapia and grouper also arrive from more distant waters, having been immediately iced, packed and flown directly to London's Heathrow airport.

It is still dark when, at 4am, a bell chimes to mark the official opening of the market and trading can commence.

The only people permitted to move fish were traditional fish porters, a strongly unionised workforce who were employed by the merchants under by-laws dating from 1876.

However, the City of London Corporation repealed the by-laws resulting in most of the 93 fish porters being made redundant in April of this year. (Approx 35 of the 93 porters have now been rehired by the traders).

The buyers are mainly fishmongers, hoteliers and restaurateurs but a healthy percentage is made up of private individuals buying for their families.

Most of the fish is chilled, rather than frozen. Few fish and chip shops buy from Billingsgate as most buy wild-caught frozen-at-sea fish from suppliers in Iceland and Norway.

The emphasis is on freshness but some species can be "too fresh". Turbot and Dover sole suffer from a form of rigor mortis and need to "settle down" before they are ready to eat.

Fish merchant Alan Cook says: "A lot of people don't realise that the fishing depends on weather and tides. We are not looking in a field for it. It's trial and error."

By 7.30am most of the fish has already been sold and many of the buyers have left. (Pictures by Emma Lynch)

Most of the fish caught by British fishermen ends up on foreign tables, while those visiting British chip shops end up eating cod or haddock from many hundreds of miles away. Why?

You could not hope to find a more traditional fish-and-chip restaurant in Britain than Steel's Corner House in Cleethorpes, Lincolnshire.

"The trick is not to change anything," says co-owner Ian Stead. "The decor is old-fashioned but people love it. A woman from America came in one day and said, 'I came as a seven-year-old child and it hasn't changed at all'."

Opened in 1946, Steel's has been serving haddock from the fish market in nearby Grimsby ever since.

But while taste in fish remains much the same, the industry that gathers it has constantly changed. The latest change comes as the EU moves to ban the practice of throwing dead fish back into the sea.

Until the 1970s most of the fish served in the UK - largely cod and haddock - was caught by British deep-sea fishing fleets, based principally in Grimsby and Hull in north-east England, and Fleetwood on the north-west coast.

The most fertile fishing grounds were in the deep, cold seas off Iceland and Greenland.

But defeat in the "Cod Wars" with Iceland led to the decline of the fleet, which was banned from venturing within 200 miles of the Icelandic coast.

Within a decade of the end of the Cod Wars Grimsby's distant water fleet had disappeared.

Nick Triplow, author of Distant Water: Stories From Grimsby's Fishing Fleet, said many of the fishermen struggled to adapt to life ashore: "The closest comparison is with a military combat zone, where you live with the adrenaline and learn to handle it. That is what it was like for them at sea with heavy machinery, slippery decks and big waves."

Many former fishermen developed drink problems or saw their marriages break up.

Despite the rise of McDonald's, KFC and thousands of Chinese and Indian takeaway restaurants, 250 million fish-and-chip suppers are still sold in the UK every year.

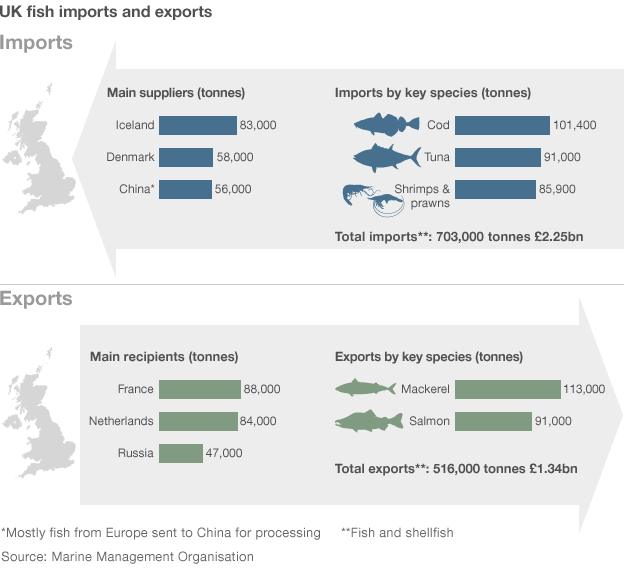

Now, with UK fleets unable to access the best spots for cod and haddock, most of it is imported from Iceland, Denmark or Norway.

"Ironically Iceland has built up its fishing industry on the back of exports to Britain," says Dr Ian Napier, a senior policy adviser at the NAFC Marine Centre in the Shetland Isles.

Scotland retains a "vibrant, active fishing industry" based in Peterhead, Fraserburgh and Shetland, with much of the catch travelling overnight by lorry for sale at London's Billingsgate market.

Scottish-farmed salmon and wild-caught cod, plus bream and brill from Cornwall, are among 150 varieties of fish and shellfish on sale there.

Vans arrive at the market from London's Heathrow airport, bringing warm-water species, such as grouper, tilapia, parrot fish, red snapper and squid, in chilled containers.

Many of the customers are from ethnic minorities where fish is an important part of their culture.

Horace Francis, who is of Jamaican origin, told the BBC: "I come down once a twice a month to buy stuff for the family. The kids like fish. It's mainly snapper and bream.

"If we're cooking snapper it will be steamed or in a brown stew with vegetables, lots of fish seasoning, Caribbean-style, with a kick to it."

But a lot of fish caught by British fishermen bypasses Billingsgate and is exported to France, Spain, Italy, Russia and Japan. Nigeria is a major market for dried fish.

Elizabeth Stevenson's family firm runs a fleet of boats out of Newlyn, Cornwall and exports most of her catch of turbot, monkfish, megrim and brill to France and Spain.

"If it's landed at 3am today, it will be auctioned at 6am, packed up in special perforated paper and put on lorries by 3pm, chilled on ice," she explains. "It will go on the ferry from Plymouth or Poole and be in Paris by tomorrow morning."

Successive UK governments have encouraged the consumption of fish - especially oily fish like salmon, mackerel or herring - on health grounds.

But Britons are fiercely loyal to cod - 800,000 tonnes are caught globally every year, and about a quarter of that is consumed in the UK.

"There are lots of different species that consumers could be eating, but we are very conservative in this country and we are [governed] by consumer patterns," says Barrie Deas, chief executive of the National Federation of Fishermen's Organisations.

Grimsby imports Icelandic cod, which arrives in chilled containers from nearby Immingham docks.

Atlantic Fresh Limited supplies up to 20,000 tonnes of Icelandic fish a year, and the company's managing director, Orn Jonsson, says: "Iceland and Humberside have been doing business for over 100 years and there is a lot of Icelandic investment in the seafood cluster."

The Jubilee Spirit preparing to sail from Grimsby. It was away for 10 days hunting flatfish.

The Grimsby area is responsible for processing 80% of the UK's seafood and is home to a cluster of firms such as Seachill, Coldwater and Sealord, which have exclusive deals to supply fish products to Tesco, Marks and Spencer and Waitrose respectively.

Earlier this year the Morrisons supermarket chain announced plans to create 200 jobs in the area by creating its own seafood processing factory.

Grimsby may be Britain's fish-processing capital, but nowadays only a handful of trawlers call it home and all are fettered by the Common Fisheries Policy.

It is an expensive business to run a trawler and skippers often have to go long distances to fish.

Retired Grimsby trawler skipper Dennis Avery: "They fish in a lot worse weather than we did, now."

"You have to make every day count, so you have to be 'on the fish' as soon as possible," says Ross Crookes, skipper of the Jubilee Spirit, standing on the dockside at Grimsby.

"It takes 24 hours to get to the coast of Norway. We are looking for flatfish, maybe 300 or 400 boxes of sole or plaice," he said as he prepared to set off on a 10-day trip.

The plaice may end up in one of Britain's 8,500 fish and chip shops.

According to the Office for National Statistics the average price of a fish-and-chip supper rose from £2.42 to £4.74 between 1996 and 2011. But the rise is thought to be largely due to fuel costs.

It's still value for money, argues Gregg Howard, president of the National Federation of Fish Friers. "If you go into an Indian takeaway with £5 you wouldn't get much, but that £5 will buy you wild-caught frozen-at-sea cod, and chips."

- Published13 June 2012

- Published12 June 2012

- Published17 December 2011

- Published4 March 2012