Nazi legacy: The troubled descendants

- Published

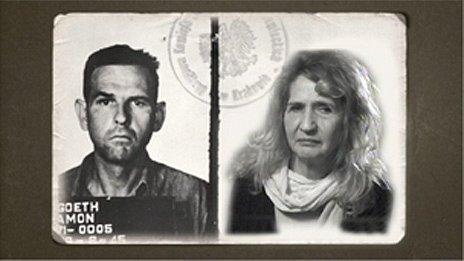

Amon Goeth's daughter Monika only learned the true extent of her father's war crimes when she watched the film Schindler's List

The names of Himmler, Goering, Goeth and Hoess still have the power to evoke the horrors of Nazi Germany, but what is it like to live with the legacy of those surnames, and is it ever possible to move on from the terrible crimes committed by your ancestors?

When he was a child Rainer Hoess was shown a family heirloom.

He remembers his mother lifting the heavy lid of the fireproof chest with a large swastika on the lid, revealing bundles of family photos.

They featured his father as a young child playing with his brothers and sisters, in the garden of their grand family home.

The photos show a pool with a slide and a sand pit - an idyllic family setting - but one that was separated from the gas chambers of Auschwitz by just a few yards.

Rainer Hoess (left) visits the Auschwitz villa where his father lived

His grandfather Rudolf Hoess (not to be confused with Nazi deputy leader Rudolf Hess), was the first commandant of Auschwitz concentration camp. His father grew up in a villa adjoining the camp, where he and his siblings played with toys built by prisoners.

It was where his grandmother told the children to wash the strawberries they picked because they smelled of ash from the concentration camp ovens.

Rainer is haunted by the garden gate he spotted in the photos that went straight into the camp - he calls it the "gate to hell".

"It's hard to explain the guilt," says Rainer, "even though there is no reason I should bear any guilt, I still bear it. I carry the guilt with me in my mind.

"I'm ashamed too, of course, for what my family, my grandfather, did to thousands of other families.

"So you ask yourself, they had to die. I'm alive. Why am I alive? To carry this guilt, this burden, to try to come to terms with it.

"That must be the only reason I exist, to do what he should have done."

His father never abandoned the ideology he grew up with and Rainer no longer has contact with him, as he attempts to cope with his family's guilt and shame.

For Katrin Himmler, putting pen to paper was her way of coping with having Heinrich Himmler in her family.

"It's a very heavy burden having someone like that in the family, so close. It's something that just keeps hanging over you."

Himmler, key architect of the Holocaust, was her great-uncle, and her grandfather and his other brother were also in the Nazi party.

She wrote The Himmler Brothers: A German Family History, in a quest to "bring something positive" to the name of Himmler.

"I did my best to distance myself from it and to confront it critically. I no longer need to be ashamed of this family connection."

Schindler's List featured Amon Goeth as a major character

She says the descendants of the Nazi war criminals seem to be caught between two extremes.

"Most decide to cut themselves off entirely from their parents so that they can live their lives, so that the story doesn't destroy them.

"Or they decide on loyalty and unconditional love and sweep all the negative things away."

She says they all face the same question: "Can you really love them if you want to be honest and really know what they did or thought?"

Katrin thought she had a good relationship with her father until she started to research into the family's past. Her father found it very hard to talk about it.

"I could only understand how difficult it was for him when I realised how difficult it was for me to accept that my own grandmother was a Nazi.

"I really loved her, I was fond of her, it was very difficult when I found her letters and learned that she maintained contact with the old Nazis and that she sent a package to a war criminal sentenced to death. It made me feel sick."

Trying to find out exactly what happened in her family's past was hard for Monika Hertwig. She was a baby when her father Amon Goeth was tried and hanged for killing tens of thousands of Jews.

Goeth was the sadistic commander of Plaszow concentration camp, but Monika was brought up by her mother as if the horrors had never happened.

As a child she created a rose-tinted version of her father from family photos.

"I had this image I created [that] the Jews in Plaszow and Amon were one family."

Bettina Goering chose to be sterilised to ensure the family name did not continue

But in her teens she questioned this view of her father and confronted her mother, who eventually admitted her father "may have killed a few Jews".

When she repeatedly asked how many, her mother "became like a madwoman" and whipped her with an electric cable.

It was the film Schindler's List that brought home the full horror of her father's crimes.

Goeth was played by Ralph Fiennes and Monika says watching it "was like being struck".

"I kept thinking this has to stop, at some point they have to stop shooting, because if it doesn't stop I'll go crazy right here in this theatre."

She left the cinema suffering from shock.

For Bettina Goering, the great-niece of Hitler's designated successor Hermann Goering, she felt she needed to take drastic action to deal with her family's legacy.

Both she and her brother chose to be sterilised.

"We both did it... so that there won't be any more Goerings," she explains.

"When my brother had it done, he said to me 'I cut the line'."

Disturbed by her likeness to her great-uncle, she left Germany more than 30 years ago and lives in a remote home in Santa Fe, New Mexico.

"It's easier for me to deal with the past of my family from this great distance," she explains.

While Bettina decided to travel far from the site of her relatives' crimes, Rainer Hoess decided he had to visit the heart of his family's shame - Auschwitz.

As a child he was not allowed on school trips to Auschwitz because of his surname, but as an adult in his forties, he felt the need to face "the reality of the horror and the lies I've had all these years in my family".

Seeing his father's childhood home he broke down and kept repeating the word "insanity".

Zvika, holocaust survivor, embraces Rainer Hoess

"It's insane what they built here at the expense of others and the gall to say it never happened."

He could not speak when he saw the "gate to hell". In the visitors centre he encountered the raw emotion of descendants of camp victims.

One young Israeli girl broke down as she told him his grandfather had exterminated her family - she could not believe he had chosen to face them.

As Rainer spoke about his guilt and shame, a former Auschwitz prisoner at the back at the room asked if he could shake his hand.

They embraced as Zvika told Rainer how he gives talks to young people, but tells them the relatives are not to blame as they were not there.

For Rainer this was a major moment in dealing with the burden of his family's guilt.

"To receive the approval of someone who survived those horrors and knows for sure that it wasn't you, that you didn't do it.

"For the first time you don't feel fear or shame but happiness, joy, inner joy."