PPI: The unintended consequences of a scandal

- Published

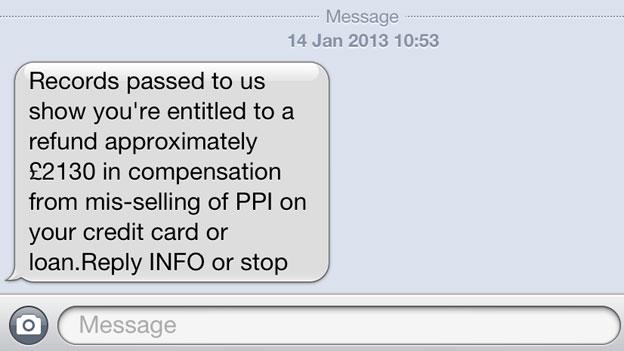

This is an example of one of the spam texts that has annoyed millions of Britons in recent years. It is one of the unintended consequences of the PPI mis-selling fiasco.

The battle over Payment Protection Insurance (PPI) has changed the face of the financial services industry in the UK.

PPI was designed to cover loan repayments if the policyholder became ill, had an accident or lost their job. But the policies were mis-sold on a massive scale to those who did not want or need them, or who would have been unable to make a claim.

And the move to compensate the victims has had some strange consequences.

Spam texts

Citizens Advice believe customers should not have to suffer more than they do already.

A huge PPI compensation industry has developed, populated by claims management companies (CMCs).

They act on customers' behalf and then take a slice of the payout. Critics argue that CMCs are not needed because people can make their own claims, but the companies say many of these people would never claim at all.

Some CMCs are alerted to potential customers by agencies that deal in leads generated by unsolicited text messages or recorded calls ("press '5' to speak to our claims department").

Most mobile phone owners will have received a text that says something like "we have been trying to contact you regarding your PPI claim, we now have details of how much you are due", or "Important - you could be entitled to £4,856 in compensation from mis-sold PPI. Reply for info."

It's singularly unwise to reply. The texts are a lie. The spammer responsible has no records relating to the recipient.

The senders are often based overseas and, if they get a positive reply, sell on the details to agencies for as much as £200 each. In the same way as unsolicited phone calls, they are sent out in automated batches, rather than referring to an individual recipient's circumstances.

In one case, the Information Commissioner's Office (ICO), which polices data protection, has been investigating a company that offered to send out more than 800,000 texts a day on behalf of clients.

"We are totally against these operations," says Andy Wigmore, spokesman for the Claims Standards Council, a trade body for CMCs.

"There are about three organisations flooding the UK with marketing messages. If CMCs are found to have purchased data that can be traced back to unsolicited messages, it is unlawful."

But he says it is often difficult to tell which leads have come from spam texts, and which have come from legitimate research of customers who have given permission to be contacted.

There are some rules designed to protect consumers. Companies must not send "persistent and unwanted" communications by telephone, fax, mail or email. The messages must include the company's name and details of how to opt out, and companies must make it simple for people to opt out.

Meanwhile, the ICO is chasing spammers, leading to a "dramatic decrease" in activity, says Wigmore.

The wow factor

So far, just over £8bn has been paid out in PPI compensation since January 2011, according to the latest figures from the City watchdog, the Financial Services Authority, external (FSA). Banks and building societies have set aside a staggering £13bn to cover the costs and compensation but this bill could go higher.

The scale of these numbers has taken pretty much everyone by surprise. This includes the FSA, which made an initial estimate of £3bn, and the banks which have been increasing their provision ever since.

While some of the total figures have been eye-watering, so have some of the payouts to individuals.

The average compensation level is £2,750. However, some people with very old claims are repaid interest that they paid in the past. This is because their PPI premiums were part of the loan, rather than an upfront payment.

When interest is added to interest - known as compounding - the figures can build and build.

For example, one businesswoman from Hertfordshire was repaid £65,000.

"I nearly fell off my chair," she told the BBC. "I was absolutely staggered at the amount, I had no idea it was going to be anywhere near that."

Unexpected windfalls

Most successful claimants receive hundreds, or thousands, of pounds, in PPI compensation. The government-backed Money Advice Service, external says that 85% of claimants eventually get a payout.

This can be particularly welcome during a time when household budgets are squeezed.

Of course, the perception of a happy windfall is slightly skewed.

This is money that people are owed to put them back into the position they should have been in, had they not been mis-sold PPI in the first place.

But with the feeling of a windfall, they may well go out and spend it in the shops.

"This was disposable income that people did not think they were going to get," says Rahul Sharma, director of retail consultancy Neev Capital.

"It may be one of the factors why Christmas beat expectations for many retailers."

Firm research on exactly what people do with the money is yet to be released.

Job creation

When the PPI scandal was first uncovered, few would have appreciated the mini-jobs boom it would spark.

But when a mess has been made, somebody needs to clean it up.

The banks fought a long, and bitter, legal battle to prevent a review of past PPI sales.

Lloyds was the first to budge in May 2011 after the legal battle was lost, inviting customers who believed they had been mis-sold PPI to get in touch.

Since then, it has said that 25% of claims are from people who never had a PPI policy with the bank, but it has to process these claims anyway. These phantom claims have been received by other banks and building societies too.

The banks had to set up vast call centres to deal with claims, despite cutting jobs elsewhere in their businesses. There were reports of banks hiring up to 6,000 workers, external to process complaints.

The Financial Ombudsman Service, independent adjudicator of disputes between customers and financial institutions, is to take on an extra 1,000 staff to deal with a record 245,000 PPI cases in the 2013-14 financial year, according to its recently published plans and budget, external.

Tony Boorman, deputy chief ombudsman, says cases are become more "complex and harder-fought".

Some institutions are frustrating customers with "delays and inconvenience" by taking cases to the ombudsman. Still, it is the financial services sector that picks up the bill - the ombudsman is funded by a levy on the industry.

The pre-emptive strike

Consumer group Which? says that some bank staff were on an 87% commission for selling PPI. Meanwhile, PPI policies were bringing in the bucks for the banks.

This created a fertile breeding ground for mis-selling, according to banking experts.

"Incentive schemes on PPI were rotten to the core and made a bad problem worse," said Martin Wheatley, managing director of the FSA, the City watchdog, in a recent speech.

So where were the regulators, like the FSA?

It says that had it had more powers available, it could have moved sooner to shut these policies down.

So, as a direct result of the PPI fiasco, and other mis-selling scandals, its successor will have the possibility of pre-emptive strikes in its armoury

Wheatley will take charge of a new body, the Financial Conduct Authority, this year. It will be able to ban "risky financial products" immediately, with the aim of avoiding lengthy and costly compensation schemes years later.

Consumers bite back

Barclays customers demanded "better banking" in 2012

British people are often seen as too polite to complain much.

So has the PPI scandal meant consumers have discovered a new confidence to take on big business if they think they have been wronged?

A recent review by the Institute of Customer Service, external suggested that UK consumers faced fewer problems when buying goods and services than they did five years ago, but those affected were more likely to complain.

Marc Gander, of the Consumer Action Group, external, says that PPI "must have made a difference" in encouraging people to complain about all sorts of issues.

Websites offering discussion forums and downloadable complaint forms, allowing people to claim themselves, really got into their stride during the saga over bank overdraft charges, external, and PPI has maintained that momentum.

But Gander says that the new found confidence is not universal.

"Banks, lenders, retailers, and mobile phone companies are still getting away with all sorts of things because of a lack of knowledge, understanding and confidence among customers," he says.

You can follow the Magazine on Twitter, external and on Facebook, external