Warsaw Ghetto: The story of its secret archive

- Published

Throughout the bitter days of the Warsaw Ghetto, a clandestine group of researchers compiled a vast archive detailing every aspect of life in this prison city built and then obliterated by the Nazis. Led by a historian, Emanuel Ringelblum, the group then buried the archive for for future generations.

On the hot night of 3 August 1942, 19-year-old David Graber signed his name on a piece of paper and put it inside a metal box at 68 Nowolipki Street, in the heart of the Warsaw Ghetto.

"I would love to see the moment in which the great treasure will be dug up and scream the truth at the world," he wrote. "May the treasure fall into good hands, may it last into better times, may it alarm and alert the world to what happened… in the 20th Century… May history be our witness."

David knew that he might have only hours, or minutes. German soldiers had arrived in the next street. Two weeks before, they had begun to drive the half-million Jewish men, women and children living in the ghetto into trains taking them to the new death camp at Treblinka.

On 2 August, 6,276 people had been taken. On 3 August, another 6,458 were seized.

With David was another teenager, Nahum Grzywacz, and a teacher, Israel Lichtensztajn. The three were part of a colossal, secret attempt to record every detail of ghetto life in an archive - David's "great treasure". The codename for this project was Oyneg Shabbes (Joy of the Sabbath).

The Oyneg Shabbes collaborators had amassed tens of thousands of documents by August 1942. Some were written, in the form of diaries, essays and commissioned surveys, poetry and precise reportage in Yiddish, Polish and other European languages.

Others were gathered. Hundreds of paintings, sketches, maps, tram tickets, recipes and even photographs secretly developed in the ghetto were carefully wrapped in paper and stored.

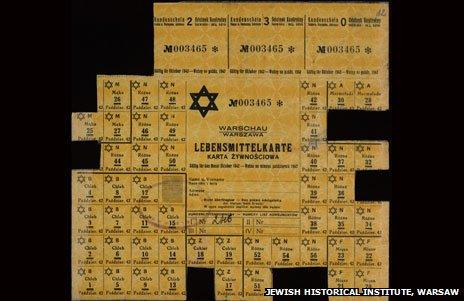

Unearthed from the archive

Food coupons and an official ration card - rations were limited to 189 calories a day, and a quarter of the ghetto population starved to death

Sweet wrappers such as this were collected by the Oyges Shabbes group - a ghetto workshop made caramels and artificial honey from saccharine

'Portrait of a Girl with a Ball', one of 300 watercolours by Gele Sekstajn who died in 1943 - "I think I am the last surviving Jewish painter," she wrote

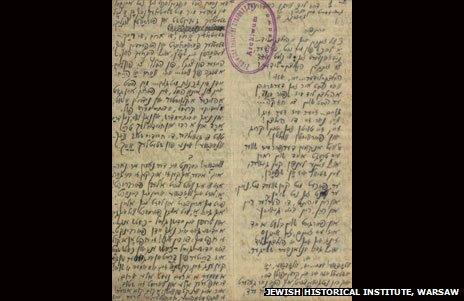

'Song of the Rebbe of Radzyn', a poem by Yitzhok Katzenelson, exploring responses to death - the poet also ran an underground children's school

Concert poster - many musicans were imprisoned in the ghetto, and a symphony orchestra, choirs and chamber groups often performed

The researchers filled 10 of the metal boxes, bound them with cord and hid them inside the brick foundations of 68 Nowolipki, an old school building.

"I only wish to be remembered," reads Lichtenstzajn's last note on behalf of himself and his wife, a well-known artist. "I wish my wife to be remembered, Gele Seksztajn. I wish my little daughter to be remembered. Margalit is 20 months old today."

The man behind the Oyneg Shabbes was a historian and social activist, Emanuel Ringelblum.

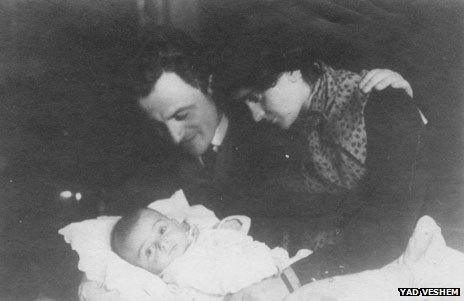

Ringelblum with wife Yehudit and son Yuri before the war, then a teacher

He was living with his wife and young son in Warsaw when the armies of Germany advanced through Europe and into Poland - the heartland of European Jewry.

Polish Jewish families in their tens of thousands were driven into walled prison cities known as ghettos, or fled to Warsaw thinking they'd be safe in a modern capital in which every third person was Jewish. They were not.

"The Saturday the ghetto was introduced was terrible," wrote Ringelblum in November 1940. "People in the street didn't know it was going to be a closed ghetto, so it came like a thunderbolt."

Ringelblum began by recording each day himself. But gradually he invited more and more trusted contacts to join in. Some wrote in Polish, but most in Yiddish.

To Ringelblum, the revival and maintenance of Yiddish was of paramount importance, in a population filled with intense debate about its identity and under pressure as never before. Each document provides a precise and personal insight into life in a community that still hoped and planned for peace.

Snatched photographs show smugglers vaulting the three-metre wall with the sacks of food which helped the majority just avoid starvation.

A recipe for frozen potatoes, an article on rotten fish cooked with saccharine and synthetic honey speak of how far those scraps of food stretched.

Researchers logged the words to the cries of beggars, and advertisements for umpteen adult education classes from physics to paper flower making.

"Everyone wrote," recorded Ringelblum. "Journalists and writers of course but also teachers, public men, young people - even children. A tremendous amount was written... a photograph of life."

Commissioning, writing and collecting was structured tightly. Secretaries made copies in triplicate, in case the project was uncovered, even using the typewriters and carbon paper of the Judenrat, the Jewish council set up by the Germans. No single person knew the whereabouts of all the documents, in order to create a security firewall.

Each document reveals the sharp, bright detail of real life. We meet the poet, Wladislaw Szlengel, as he sits by his phone in the ghetto, looking through his window to the park on the other side. The phone still works - but he has no one to call in the other Warsaw beyond the wall, the one he called home before 1940.

The bitter jokes in the archive still work: "Hitler comes to the other world. Sees Jesus in Paradise. 'Hey, what's a Jew doing without an armband?' 'Let him be,' answers St Peter. 'He's the boss's son.'"

Other testimonies mark the many who died without trace.

"Terrible case of a three-year-old refugee child," Ringelblum writes of a family sent by train to the ghetto. "The guard threw the child into the snow. Its mother jumped off the wagon and tried to save the child. The guard threatened to shoot all the Jews in the wagon. The mother arrived in Warsaw and here went out of her mind."

The concert programmes and tickets preserved give a glimpse of names once famous in what had been a sophisticated European capital. There are performances by world-class musicians from the Warsaw Radio Orchestra and the Philharmonic.

Staff from the Electro-Syrena record company were also confined within the ghetto. The first record label in Poland, Electro-Syrena, had been bringing out popular dance music in Polish and Yiddish since 1904, a back-list of 14,000 titles. In the long summer of 1939, weeks before the German invasion, it produced a smokey foxtrot that would be its last record.

One of the label's greatest stars, the elegant Artur Gold, was so famous to his German captors that they made him perform at Treblinka, wearing a clown suit, before they killed him.

David Graber, Nahum Grzywacz, Israel Lichtensztajn, Gele Seksztajn, 20-month-old Margalit, Emanuel Ringelblum, Yehudit Ringelblum, Uri Ringelblum, the poet Wladislaw Szlengel, the orchestras, the staff of the Electro-Syrena label, Artur Gold - none of them survived the war.

Nor did Nowolipki Street. In 1943, after the ghetto uprising, German soldiers blasted the shabby streets still standing into rubble and ash.

But three members of the Oyneg Shabbes inner circle did come through.

In September 1946, after weeks of planning and calculation, they estimated where the hiding place must have been and dug beneath the rubble. The 10 boxes were still there, intact, and the papers legible, bar some water damage.

35,000 documents from the archive were unearthed in 1950

Then in 1950, labourers at one of the new post-war housing estates in what was now communist Warsaw stumbled upon two metal milk churns filled with documents.

Around 35,000 documents were recovered in total. All efforts to find the last cache - the biggest - have failed.

Most recently, archaeologists looked under the garden of the Chinese embassy on what was Nowolipki Street, but found nothing but the burnt scraps of a diary.

The rest of the archive may still be under Warsaw.

You can follow the Magazine on Twitter, external and on Facebook, external