Les Miserables: What makes people cry in films?

- Published

SPOILER ALERT: Lucy Wallis and an audience are filmed watching Les Miserables. Where will they cry?

Oscar-nominated Les Miserables has joined the pantheon of movies that make people cry. But what things make people blub in the cinema?

(Spoiler warning - piece contains extensive plot details)

There was always a hint in the title that Les Miserables could make you feel at times - well miserable.

As a self-confessed Les Mis fan, there was always something that struck me about this musical based on Victor Hugo's 19th Century novel - I always cry at the same moments.

But it is not just me. I started to notice others in the audience at the West End musical rustling for the tissues among the empty sweet wrappers in their pockets at the same time.

In a non-scientific study I wanted to see if these "teardrop" moments also applied to the Oscar-nominated film, and so I went along to a screening of the movie with some fellow film-goers where our reactions were filmed using night-vision cameras.

The musical has been seen by more than 60 million people worldwide.

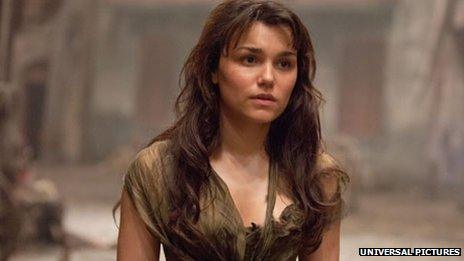

Anne Hathaway is tipped for Oscar success for her role as Fantine

"Les Miserables is known for causing people immense emotional response. So people go expecting to be moved and are prepared to let themselves go," says psychologist Averil Leimon.

The story - a tale of revolution, love, desperation and redemption - is set in post-revolutionary France and follows the lives of characters Jean Valjean, Fantine, Cosette, Marius and Eponine.

It is only a short while into the film when the first tear-jerker moment arrives and the tears uncontrollably stream down my face. Fantine is betrayed by her fellow factory workers for having an illegitimate daughter and is dismissed into a life of despair. I feel frustrated for her.

"Witnessing unfairness and injustice causes a stress reaction," says Leimon. "It springs from instinctual, evolutionarily determined responses at brain level rather than from logical assessment of the facts. It is something so fundamental to us that we are outraged, even when we know that other people do not necessarily hold the same moral values as us."

Eponine longs to be loved - something every human being aspires to

Fantine's hopeless struggle to protect her child is painful to watch and Leimon says that mothers in particular can be more likely to identify with Fantine's agony.

"They are not so much thinking about the mother and child on screen but about the immense pain they would feel if in that situation themselves."

There is no respite from the sorrow and in a desperate attempt to get money to support her daughter, Fantine sells her long hair. The moment it's cut off can be especially difficult for women to watch, says Leimon.

"Hair is such a signifier of femininity. It has such an intimate connection with the individual that even though she chose this action, we perceive it as an invasion."

Leimon says we often identify long hair with youth, so we perceive Fantine as ageing.

Having been drawn into prostitution to raise money for her child, Fantine reflects on her broken dreams and the lover who left her in the song I Dreamed a Dream. Here for many people the full waterworks come on.

For Anne Hathaway who plays the character onscreen, this moment was recognition that Fantine, who she says is a dreamer, has lost part of her soul.

"When she says now life has killed the dream I dreamed there's no turning back," Hathaway says, external. "Once something's dead it's dead, and that is the moment for her when she gives up everything she knows about herself that she holds dear."

We cannot be comforted by any type of optimism and it is the music in particular that incites the sense of loss according to Mary Hammond, Sondheim Professor of Musical Theatre Vocal Studies at the Royal Academy of Music. Hammond was one of the vocal coaches who worked with the first cast of Les Miserables in London's West End.

"The way we produce the voices in Les Miserables is not quasi-classical technique. We were exploring how your voice had to express what you were feeling… As I understand it the original characters all came out of acting improvisation, so the original people that did it all developed those characters with the director."

It is likely that everyone on some level might experience the sadness of what it feels like when life does not go to plan, as with Fantine's dreams, and it is the gap between desired and actual experience, according to Leimon, that makes us so upset.

With red eyes and not enough time to recover from this epic song, we move quickly on to the next teary moment - Fantine's death. As her path crosses with Valjean, he promises to look after her daughter, but in her delirium Fantine imagines her child Cosette is playing beside her - a moment which brings on another flood of tears.

A dying parent's goodbye to a child is a classic moment in a slew of tear-jerkers. Take the death of Emma, played by Debra Winger, in Terms of Endearment, as she says farewell to her two children.

Fantine is so young. It's what makes the death of Jenny (Robin Wright) in Forrest Gump poignant for audiences.

We are often protected from witnessing death in real life, says Leimon. Add to this the fact that major life events tend to happen over a period of years in real life, whereas in the cinema they are all condensed into a couple of hours, and it's easier to explain the "constantly heightened emotional state" of some viewers.

Under Valjean's protection, Cosette grows up and falls in love with Marius, a revolutionary student who fights on the barricades for the rights of the poor in the anti-monarchist Paris Uprising of 1832.

But this is a heart-breaking love triangle and Eponine, Marius's friend, dripping wet in the rain, imagines what it must be like to be in a relationship with him in the song On my Own. Romantic entanglements can also prompt tears.

"By the time we reach adulthood we are geared to look for love. To find it but not have it returned is tragic," says Leimon.

Jean Valjean struggles to free himself from persecution despite his moral virtues

For Hammond, the song always invokes the feeling of wanting to escape from everyday life. It is this sense of escape that people can relate to.

With no time to recover from our snivels, Eponine follows Marius to the barricades to fight alongside him, is shot and dies in his arms. It's on a par with the scene where Nicole Kidman's character Satine dies in Ewan McGregor's arms in Moulin Rouge.

The next teary-eyed moment involves Marius and his fellow students as they fight a losing battle with the National Guard and are slaughtered on the barricades.

Fictionalised struggle affects people emotionally in an echo of the way real struggle does. Scenes like this can particularly affect men, Leimon suggests.

The death of the young in battle has been a tear-inducing theme in hundreds of films. Think of Saving Private Ryan, when a dying Captain Miller (Tom Hanks) turns to Private Ryan with the words "earn this... earn it", demanding his death not be in vain.

I am emotionally exhausted, but then we come to it - the final and biggest teary-eyed scene in the film - the death of protagonist Jean Valjean. Haunted by his past, Valjean flees to a convent and in his dying moments sees the spirit of Fantine appear to him.

We know he is about to die, but why is this so painful to watch?

"We have identified so intensely, seen more of that person and their emotions than we may have with our family and friends, that we have short circuited the process of bonding that would take a lot longer in real life," says Leimon.

By the end of the film I was an emotional wreck, but I did not feel sad and maybe this is the eternal appeal of this production. Although it can tap into your most primal anxieties and fears, you can still want to watch it all over again.

You can follow the Magazine on Twitter, external and on Facebook, external