Fashion: The accountant who created the first book of fashion

- Published

Costume designer Jenny Tiramani dresses model Jack Brotchie in a recreation of one of Schwarz's elaborate outfits

How did a 16th Century accountant end up creating one of the most unique documents in the history of fashion - the world's first fashion book?

Creating fashion history is not something you would normally expect from an accountant.

But in an extraordinary undertaking spanning 40 years a style-obsessed accountant from Augsburg in Germany recorded in detail what he wore, creating what historians now think is the world's first fashion book.

Interested in clothes from a young age, Matthaeus Schwarz started commissioning watercolour paintings of himself at the age of 23 and continued until he was 63. No other pictorial record like it exists, say experts.

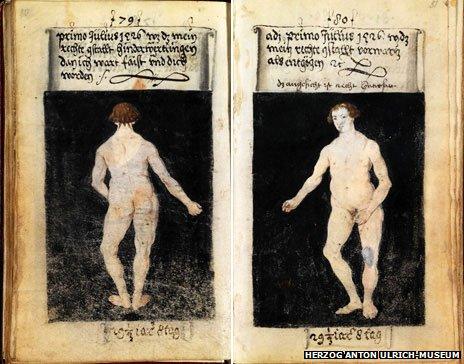

Matthaeus Schwarz posed for his first portraits aged 23. He posed nude aged 29, noting: "That was my real figure from behind, because I had become fat and large."

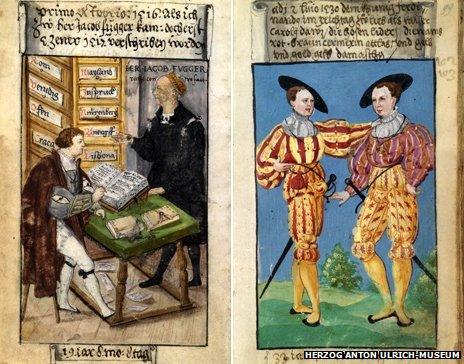

Schwarz's first employer Jacob Fugger the Rich (depicted left in black clothing), is the only other person to feature as a life-size adult figure in the paintings. Researchers recreated the red and yellow outfit on the right (see video above).

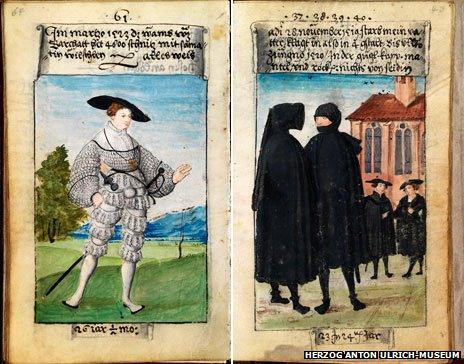

The portraits covered key moments of Schwarz's life, including his father's death when he was depicted in four types of mourning dress (right). He was also captured wearing an intricate doublet with 4,800 small cuts called "pinks" (left).

On his 41st birthday Schwarz was painted from behind wearing a thick cloak he had made for his wedding. Another showed him in black to mark the Moritz of Saxony's death, roses symbolising what he saw as a victory for Catholicism.

"What he produced is one of the most unique documents ever created in the history of fashion - it is a treasure trove of information," says Dr Ulinka Rublack, reader in Early Modern European History at the University of Cambridge and author of Dressing Up: Cultural identity in Renaissance Europe."

The book is kept in a small museum in Braunschweig, Germany. It has not been widely studied until now and Schwarz himself has been viewed by historians as a bit of a curiosity, says Rublack, who rediscovered the book.

She says he was in fact an innovator who pushed style boundaries. His book also challenges established ideas about historical fashion, particularly that only the very rich were stylish.

Schwarz was the head accountant for the Fugger family, one of the most important and wealthy German merchant and banking families at the time.

He started to record his appearance in 1520, initially commissioning 36 images to retrospectively cover his appearance from childhood up until the age of 23. Over four decades he commissioned a total of 137 original watercolour images of his outfits, painted by three principal artists.

He continued until he was 63 and then had the pages bound, creating what became known as the Schwarz Book of Clothes.

What makes Schwarz so remarkable is that he was one of the first people to be interested in fashion as a cultural phenomenon, says Rublack.

"At the time wealthy Germans were serious about dressing properly but considered it foolish to be into fashion in its own right."

Schwarz was an innovator, playing with his style and exploring new cuts, colours, fabrics and details. He had fun with clothes.

'Pinking'

It wasn't always easy. During his lifetime there were strict social conventions and rules surrounding clothes. Sumptuary laws, made for the purpose of restraining luxury or extravagance, stipulated the dress and jewellery appropriate for a person's rank. So while he pushed boundaries, there were lines he had to be careful not to cross.

An employee was definitely not allowed to dress more extravagantly than his or her employer and often forbidden from wearing certain items. For Schwarz there was a further complication, his extremely wealthy employers were worried about being seen as excessively rich and were consciously trying to dress down, says Rublack. He had to be clever and he was.

"If sumptuary laws banned a certain item of clothing or accessory he would push a different way," says Maria Hayward, a professor of Early Modern European history at the University of Southampton who specialises in textiles and clothing.

"If fancy hose were forbidden for example, he might have gone for fancy sleeves instead."

He went to great lengths to create outfits. Unlike today there were no luxury brands he could buy off the peg.

Working for important merchants he had access to fine materials and the contacts to get whatever else he needed. He would employ skilled craftspeople, says Jenny Tiramani, theatre designer and principal of the School of Historical Dress. Everything would have been done by hand as the sewing machine hadn't been invented.

Schwarz also went to great expense. He wasn't rich but had a good income and he chose to spend most of it on his appearance.

Many of his outfits were remarkably elaborate. One watercolour painted just after his 26th birthday shows him in a spectacular white hose - clothing for the legs and lower body - and doublet - a fitted garment worn on the upper body that was tied to the hose around the waist (outfit pictured in slideshow).

At the time it was fashionable to "pink" clothes. This was a technique where a sharp chisel was used to slice through material creating a slash. Notes made by Schwarz reveal his doublet had a staggering 4,800 small pinks.

The colours he wore and the accessories often had specific meaning and significance. White, used for this particular outfit, represented faith and humility.

Intent and idealisation

He would diet to get the fashionable body shape of the time and dressing wasn't a quick or easy affair either. He would have needed servants to help him and often they would have sewn him into his clothes.

"A lot of time was spent arranging garments so everything looked perfect," says Tiramani. "Often a servant would have gone out with him to make sure the outfit was properly arranged at all times."

Schwarz didn't only use clothes to look good. He also used them for specific social or political reasons, from getting a promotion to courtship. He had an elaborate red and yellow outfit - recreated by Tiramani in the video above - made for the return of the Holy Roman Emperor Charles V to Germany. This was after a nine-year period during which many parts of the country had turned to Protestant faiths.

He chose the colours as they were associated with happiness and his aim was to show his allegiance to Catholicism and to the emperor, says Rublack. It worked and he was ennobled in 1541. It was a huge leap in social status.

"It's easy to dismiss Schwarz as a bit of a dandy in his brightly coloured clothes," says Hayward. "But he used clothes in a very clever way to assert lots of things about himself. His outfits weren't just what he felt like wearing, they had meaning and intent."

But there is another reason Schwarz's book is so groundbreaking, say historians. He included two naked images of himself, one from the back and one from the front. He was 29 when they were painted.

"At the time painting nudes in a secular context was extremely rare, they were usually painted in a Biblical and classical context," says Rublack. "There were no higher principles applied when it came to Schwarz's nudes, they simply documented what he looked like without any clothes on."

There was no attempt to make himself look better, which was almost unheard of at the time. "I had become fat and large," he himself notes under the images. He also had a painting done of himself while he was recovering from a stroke, aged 52. Another first, historians believe.

Vanity

In a modern world where every facet of life is documented it's hard to grasp how different this true representation was.

"His honesty is so striking and unusual," says Rublack. "People would use paintings to project a certain image of themselves but Schwarz's paintings were not idealised. He was remarkably honest about the course of life and getting old, he showed what you couldn't control as well as what you could."

He stopped recording his outfits aged 67. He tried to persuade his son to continue the project. Veit Konrad Schwarz commissioned 41 images of his own but didn't add any more after the age of 19.

Crucially for Rublack, the book challenges a common school of thought that fashion only became available to everyone in the 18th Century.

"The book changes our sense of looking at the past," she says. "It shows that fashion cannot be considered a modern phenomenon and spread down from the top social elites as early as the Renaissance."

Tiramani agrees. "It challenges the cliche that everyone who didn't attend at a royal court went around dressed in grey rags and sack cloth."

Exactly why Schwarz embarked on his book of fashion remains a mystery. It could have been purely a vanity project or he may have wanted to hand down a record of contemporary fashion at the time.

He didn't publish it but he didn't hide it either, showing it to people of his own choice. After his death the book was handed down through the family and eventually sold. Two copies were made but the original is now in the Herzog Anton Ulrich-Museum in Braunschweig.

"It's possible he wasn't the only person creating such books but his was the only one to survive, we simply don't know," says Tiramani. "But whatever his reason it's not something you'd expect an accountant to do - then or now."

You can follow the Magazine on Twitter, external and on Facebook, external.