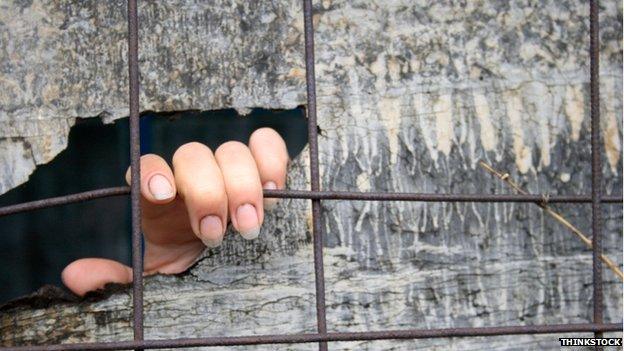

How do people survive solitary confinement?

- Published

The effect of solitary confinement on mental health can be devastating - what techniques can kidnap victims, hostages and prisoners use to get through the ordeal?

"No-one knows that you are there, so you are nothing. You are zero."

For many months, Tabir was kept in solitary confinement in a cell in North Africa, imprisoned for his political views. His room didn't have a bed or a toilet. The sole feature was a small, high window which let a wan light through.

He recalls the countless, long days passing in complete silence. But then after sunset, and stretching through till dawn, he could hear the wailing of fellow prisoners being tortured - a sound that provided some comfort, since it was a confirmation that he was still alive in a world shared with other people.

UN special rapporteur on torture Juan Mendez defines solitary confinement as a regime in which an inmate is kept isolated, seeing only guards, for at least 22 hours a day. He has called for a ban, external on incarcerating people in these conditions in all but exceptional circumstances, and with a limit of 15 days even then.

Many prisoners in "supermax" prison units in the US are kept in solitary confinement for decades.

The government says these are prisoners who have proved too violent or unco-operative to be kept in a normal cell, who are members of prison gangs, or occasionally, who have been put there for their own protection.

Unlike Tabir's cell in North Africa, the ones in the secure housing unit in Pelican Bay State Prison in California have fluorescent lights and beds. There are no windows. The rooms are a little larger than a double bed. Prisoners get 90 minutes of exercise a day. The rest of the time is spent staring at the steel door and the smooth concrete walls - or the television.

Although the environment is cosmetically different from the "holes" in which hostages and prisoners like Tabir are kept, the effects of isolation are similar.

"Some people have an immediate, profoundly negative reaction to it," says Craig Haney, a professor of psychology at the University of California, Santa Cruz, who has studied the impact of solitary confinement on the inmates of Pelican Bay.

"For some people, there is something terrifying about being placed in an environment where you are completely alone, isolated from others and where you cannot connect to other people."

Those inmates not affected by this "isolation panic" may still slip into long-term depression and hopelessness. Then the environment takes its toll on cognitive ability, as the prisoners' intellectual skills begin to decay. They may suffer lapses in memory. At the most extreme, prisoners could even undergo a complete breakdown.

"There are instances of people who literally go insane in solitary confinement - I've seen it happen," says Haney. "That's an extreme case of somebody's identity becoming so badly damaged and essentially destroyed that it is impossible for them to reconstruct it."

But prisoners can take steps to mitigate the psychological effects of solitary.

The first thing they should do is take control of their space, says David Alexander, a psychiatrist and trauma expert. He is the principal adviser to Hostage UK, a charity that helps victims of kidnap.

Very often hostages will be kept in conditions similar to Tabir's, without toilets or washing facilities.

"It's filthy - well, let's clean it," says Alexander. "It's not a nice job. You start scraping the filth to one end. You designate one corner for pee. Pee runs downhill so don't put your pee corner at the top of the room."

He recommends creating a "living quarter" within the cell, to be kept as clean as possible. Prisoners should also try to keep themselves clean, he says.

"Pick your nails with your own nails - if they are rough and broken scrape them on the walls - every effort you can make to try and retrieve your identity, which is part physical, part psychological."

With no communication for days on end and a complete loss of contact with the outside world, hostages and prisoners sometimes wonder whether they still exist.

Tabir spent the nights talking or singing to himself to recapture a sense of his physical presence. At his most desperate, he found himself picking fights with his guards. In the US prison system, this is called a "cell extraction". A prisoner will refuse to comply with his orders, for example by holding on to his food tray when a guard tries to clear it away. The inevitable result - four or five armed guards come to the cell and forcibly restrain him. It may be brutal, but it's a form of human contact.

David Alexander says it is vital for hostages to establish some form of personal routine.

"Get a system going as you do at home," he says. "Anything you do to try and impose order and structure on your world, which helps your identity and helps you to try and counter what the bad guys want you to experience."

The pressure group Solitary Watch says 44,000 people are held in solitary confinement in eight US states

What they want, he says, is for prisoners to slip into what clinicians refer to as "learned helplessness". This is the feeling that whatever prisoners do will end in failure.

Like Tabir, Andre - who wishes to be known just by his first name - was kept for months in solitary confinement for his political views, this time in Eastern Europe. He experienced a series of gut-wrenching false dawns. Time and again his captors said they would release him, but each time it turned out he was just being relocated to a different prison.

They also tried to break him by repeatedly searching him - sometimes eight times a day.

"I discovered that you cannot go to extremes," he says. "You cannot be either very happy or distressed. You have to keep yourself in one piece."

Andre learned to manage his feelings, and kept himself busy, reading for hours on end. He also kept his mind active by constructing haiku poems, at times spending the whole day puzzling over which three lines most perfectly captured a memory or a feeling.

"You have to get through the day," he says. "Everybody in prison will tell you that the weeks and months are flying, while days - bored is not an accurate word, because for a prisoner every day is full of surprises."

A day came when the surprise was that he was free to leave. Andre barely reacted. "Maybe I was too deeply into my own method of not over-reacting," he says.

Many prisoners coming out of solitary confinement find they cannot shake off a feeling of emotional numbness. They may well have trouble forming relationships and trusting partners and friends.

The after-effects can also take the form of post-traumatic stress disorder - sleeplessness, anxiety, sensitivity to noise, flashbacks and depression may all be symptoms.

Then there are learned patterns of behaviour, which become an obstacle to prisoners trying to restart their lives outside the perimeter fence.

"In some eerie and tragic cases, people almost literally recreate their cells," says Craig Haney of Pelican Bay's former inmates. "One man refused to come out of the bathroom for over a month because he said it was the only room in the house where he felt comfortable. All the other rooms were too large, they made him anxious."

Many US supermax prisons release inmates without any form of transition programme, even after decades of solitary confinement.

Tabir managed to escape his captors during a stay in hospital and eventually sought refuge in the UK. Angelina Jalonen, Tabir's case-worker at the charity Refugee Council, says she is impressed with the progress he has made. She speculates that perhaps his emotional resilience is partly due to his strict upbringing, where he was expected not to show emotion.

Throughout his incarceration, Tabir was determined that even when the guards tortured him - and he still suffers from the physical wounds inflicted on him - they would not "conquer" his mind.

"Even here, now, I am fighting," he says. "I'm fighting for work, fighting for a job, fighting for a house. Fight for your rights and whatever people do, don't give up fighting.

"And smile and be happy - and don't be afraid of anybody."

You can listen to The Truth about Mental Health: Four Walls on the BBC World Service at 14:30 GMT on Friday 14 June.

You can follow the Magazine on Twitter , externaland on Facebook, external.

- Published4 April 2012