A Point of View: The road ahead for the Catholic Church

- Published

The Catholic Church is at a critical juncture. Pope Francis needs to address the scandals troubling the Church over recent decades, but risks opening a door to modernisation that may be difficult to close, says Sarah Dunant.

When the first Bibles were printed in the 15th Century not everyone rejoiced. Some felt that communicating the word of God was the Church's business and should be kept in its hands. While I'm not equating the Pope's use of Twitter with the printing press it's interesting how many people are upset by it. Of course an image of His Holiness hunched over his mobile stabbing in 140 characters feels ludicrous. But give it some thought. Social media has revolutionised the way we gather news. You can bemoan the death of serious journalism, but many celebrate the immediacy of Twitter - how, often sliding under the radar of state security, it has speed and gives a voice to the people, offering a window on to history being made. If the faithful believe in the power of the Pope, why shouldn't he speak to them directly through their mobiles? It's worth noting that the 10 commandments are all conveniently Twitter length.

So what should the Pope be saying to his millions of followers (an apt use of the term perhaps)? Well, it's hard to know where to start.

Many, even among the faithful, think the Catholic Church is in a mess. While it may not be selling indulgences (though the recent suggestion that those following the Pope could knock time off in purgatory makes one wonder), decades of financial scandal and particularly sexual abuse have exposed a level of moral decay which, if it were a democratically elected government or even a global corporation, would see voters or shareholders expressing public revulsion and fury.

Time for the disclosure. I was born and bred a Catholic. Confessed and confirmed, I spoke to God regularly from the age of five or six into my teens (He, or She, was always most comforting in moments of confusion and distress) and while I have long since left the Church, it still fascinates - witness the fact that I write novels set in Italy at one of its most dramatic and corrupt moments, the late 15th Century. For me the past is not only a lens to view the present, at times it seems there's little difference between them.

Then, as now, the Church was not short of believers. Rome in 1500 hosted a huge jubilee, which saw an army of pilgrims flooding across the Sant'Angelo Bridge towards the old St Peter's. Two years ago at pre-beatification ceremonies for John Paul II, I was caught for days inside what felt like an equal crush. Both events had their critics. In 1500 it was seen by many as a money-making marketing event for a Borgia pope intent on war. In 2011 there were suggestions that the fast-tracking of a pope to sainthood was a propaganda act. John Paul may have been considered a great guy, but some terrible stuff happened on his watch and the Church needed to be addressing that too.

For a moment it felt it might be. In historical terms I cannot tell you how "not on" it is for a Pope to resign. Benedict's leaving made public a crisis and everyone, even in conclave, seemed to accept this, by electing a man with a record of great humility in the service of God. Faced with an Augean stables, external, Francis chose not to move into the infested area, lending credibility to rumours of sex and blackmail inside the Vatican. Shocking perhaps, but is any one out there really surprised?

The connection of sex, sin and corruption has long plagued the Catholic Church as an institution. Desire can be a devil even for atheists. By the late 15th Century, with prostitution endemic and children in the sexual arena at an age we now define as criminal, celibacy was no guarantee of sexual purity. Priests, bishops, cardinals, popes... many sinned regularly - rent boys, housekeepers, courtesans, even having children. If being celibate was seen as an economic necessity for the Church to preserve its wealth then being chaste was very much an optional extra.

While it was corrupt and hypocritical, in terms of the hierarchy of sins, interestingly sex was not quite the deal-breaker it is considered now. You only have to think of Dante's circles of Hell: lust - even sodomy - is way down the list, worse than limbo yes, but trumped by gluttony, greed, anger, heresy and treachery. I recently stood halfway up Brunelleschi's great dome in Florence decoding its graphic heaven-and-hell mural with an eminent theologian and canon. When it came to the lustful - mostly men - the monseigneur talked intently about how within Renaissance society it was accepted that both before and after marriage men would sin sexually: "Before the Victorian period made such a bugaboo out of sex," (those were his words), "while it was clear that spiritual growth called for a control of our passions, there simply wasn't such a fixation on sex itself."

Next time you spot a cardinal's mitre being crammed into the mouth of a devil in a Renaissance fresco, remember they might be there for greed or avarice as much as anything else.

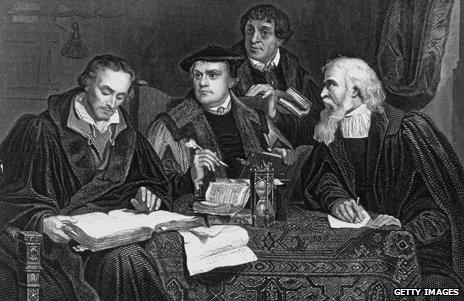

Martin Luther (second from left) and three other German reformists

Nevertheless, when the Augustinian monk Martin Luther went public on church corruption, his critique of celibacy was passionate. In 1525 he left the priesthood to marry a nun. For the church the schism was a disaster. Necessary reforms became the bedrock of a new religion and Catholicism was left to defend the old stuff, like divine authority of priesthood and celibacy.

The main doctrinal weapon left when it came to combat abuse (and while this may sound cynical I mean it very seriously) was, and is, confession and absolution. It is deeply important that when the rules are tough, there is an understanding that people will break them and need - and be given - help to reconnect with the true path. To this day I have a memory of the power of confession. I never did anything very bad (Shepherd's Bush in the early 60s didn't give me much opportunity) but it acted as a kind of moral compass. Had I lied to anyone, been unkind, selfish? What a relief to admit it and be given a fresh start.

The defining idea here is "hate the sin, love the sinner", a wonderfully compassionate concept in itself, but oh, how over the years it has come a cropper inside a secretive, hierarchical, all-male, establishment. Those priests who failed in the battle against sexual desire, using their authority to abuse those around and below them, were both forgiven and also protected, even down to being transferred to another parish without telling anyone, often to sin again. What on the inside was passed off as a new beginning, from the outside was plain criminal. Meanwhile the cover-up helped to keep the global brand intact.

For their victims it was a double nightmare. First the crime itself, then the fact that there was no redress. Before we get too high and mighty moral, think of recent revelations about sexual behaviour and power in Britain: all those young people, who were prayed upon under that most potent guise of secular authority - celebrity - then found it impossible to make their voices heard against the prevailing orthodoxy. It's not just the Catholic Church that's been caught out by changing attitudes towards male sexual behaviour.

When we make the definitive programme about the Jimmy Savile effect in British culture, film planners could do worse than double bill it with Mea Maxima Culpa, the searing documentary charting how victims in the Catholic Church began to fight back (starting with abuse in a school for deaf children), the trickle becoming a tidal wave, while the Church ignored or tried to silence them.

Pope Francis on his visit to Brazil

This then is the gangrenous wound that Pope Francis inherits. As he visits the slums of Brazil, emphasises the plight of immigrants and calls for a church of the poor, we wait patiently for him to get around to seriously addressing it.

Can he really do it? Well, if he does, the impact will be that of a Luther. Or maybe Gorbachev is better example. Since as soon as one brick is out of the wall, you can't help feeling many more will tumble in its wake. Start talking sexual abuse and you have to talk about celibacy, then attitudes to homosexuality and of course the role of women. And when you do, there are some smart, impassioned Catholics out there - a number of them women - who think the real problem is the overriding nature of priestly authority and the only way forward is a different model, more imbedded in the community, not risen above it.

Not in my lifetime, I think. Though history can take one by surprise.

As for what could be done with 140 twitter characters: Well, how about this?

"Nothing in the gospels says that women should not be priests."

"The only thing worst than corruption is cover-up."

Or someone could just re-tweet one of the Pope's own. July 10th: "If we wish to follow Christ closely, we cannot choose an easy, quiet life."

Go for it, Francis.

You can follow the Magazine on Twitter, external and on Facebook, external