How the computer changed the office forever

- Published

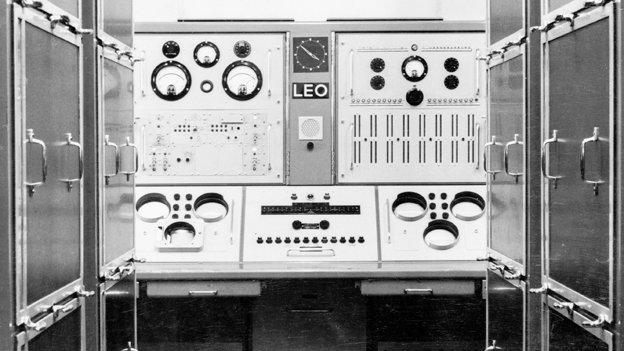

The LEO was the first computer used for commercial business applications

It was a British tea shop and catering chain that developed the first computer for business use. Since then, the computer has rewired office workers' brains, argues Lucy Kellaway.

Do you remember the office before email? Before we spent our time watching cat videos and doing surreptitious grocery shopping online?

As an experiment I turned off my office computer and kept it all off all day. I found I could think - just about - but had nothing to think about. I couldn't work, or communicate. I couldn't even skive. I was a non-person.

Today the computer is the office. Its dominant metaphor is taken from office work - it's got a desktop, files, folders, documents, a litterbin. It all seems to have happened so fast.

In 1975, Business Week ran a cover article called The Office Of The Future. In it, George E Pake, head of research at Xerox, predicted "a revolution… over the next 20 years", involving a television display terminal sitting on his desk.

"I'll be able to call up documents from my files on the screen, or by pressing a button," he said. "I can get my mail or any messages. I don't know how much hard copy I'll want in this world. It will change our daily life, and this could be kind of scary."

He turned out to be quite right. Our daily lives have changed and it has been quite scary.

The only thing he was wrong about was those hard copies - our love affair with computers hasn't ended our love for paper. It's only in the last few years we've stopped printing out every email we get sent. The joke more or less still stands that the paperless office will arrive at the same time as the paperless toilet.

The first office computers didn't come in the 1970s and 1980s. They came at least 20 years earlier in the 1950s, and not from whizzy California, but from frumpy Hammersmith.

"Electronic brains. Science fiction stuff? No. It's Britain's first computer exhibition at London's Olympia," said one advert. "The machines that take the toil out of totting up figures."

The place where these electronic brains were pioneered was a tea shop - and a British institution - Lyons.

The man behind it was John Simmons, a Cambridge mathematician who dreamt up a machine that would add up the receipts of iced buns. The 6,000-valve monster he built was called LEO - Lyons Electronic Office - and its inventor was in no doubt about the good it could do.

"Here for the first time there is a possibility of a machine which will be able to cope at almost incredible speed with any variation of clerical procedure," he said. "What effect such a machine could have on the semi-repetitive work of the office needs only the slightest effort of imagination."

To go from cupcakes to computers was one of the most unlikely diversifications in British history, and in marketing terms this was a problem, as one critic observed.

"A potential computer user needs to have some confidence in his own judgement if he is to buy his computer from a tea shop."

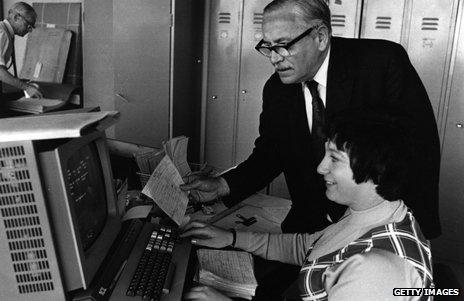

By the 1960s, the mighty mainframe computer, which was then a US import, had arrived in British offices. But Simmons's vision of the computer releasing clerks from tedium wasn't quite right.

It just swapped one sort of drudgery for another. Even the copying done by 19th Century clerks sounds interesting by comparison with the boredom of punching cards to feed into the computer. One key-punch girl described her colleagues as nervous wrecks.

"If you happen to speak to an operator while she is working, she will jump a mile," she said.

"You can't help being tense. The machine makes you that way. Even though the supervisor does not keep an official production count on our work, she certainly knows how much each of us is turning out by the number of boxes of cards we do."

What these computers dealt in were numbers. But for the average office worker the real revolution came with the arrival of the word processor.

This concept was invented by a German called Ulrich Steinhilper in the 1950s. He threw the idea of word processing into the IBM suggestion box and was paid the princely sum of 25 Deutsche Marks for it. But someone high up deemed it too complicated, and so nothing happened. At least, not for a while.

But by the 1970s, everyone felt differently. Processing was all the rage. This was the age of the food processor, and these new office machines promised to perform the same miracle with letters that the Cuisinart achieved with carrots.

The 1970s idea of word processing was very different to tapping on a laptop. The idea was that word processing would be done in pools by specialised typists working with souped-up text-editing machines.

But to women, word processing was sold as a feminist innovation. The New York Times proclaimed in 1971 that it was an "answer to women's lib advocates' prayers", because it would mean secretaries no longer had to do subservient stuff like taking dictation.

An early word processor from 1974

Yet once again, it didn't work out like that. Being bumped off to the new word processing pool turned out to be only slightly more fun that punching holes in cards.

Word processing didn't happen for the rest of us until the arrival of the desktop computer. In 1977, Apple launched the Apple II. Four years later IBM brought out the PC.

The first word processor that I used at the Financial Times in the late 1980s was a grotty machine with a sticky keyboard and dark green screen with green writing that gave me a splitting headache at the end of day.

To do anything fancy like cutting and pasting text took quite some effort - about six keystrokes and a lot of whirring.

Thankfully, things have changed. How we use computers now is so simple it's rewired our brains.

With everyone in offices learning to use these machines in the late 1980s and early 1990s, work was redistributed. Most of the grunt stuff was done by the PC, the rest, such as emailing and managing diaries, we started do ourselves.

The computer has been thrillingly liberating and thoroughly democratic. Only not so hot for the secretary, who has not only stopped doing the grunt work - she's lost her job.

The image of the computer changed too. As computers got smarter, working with them stopped being low status work for women and began to be seen as the men's domain.

"In the late 1960s and 1970s you do start to see a shift in how the computers are being marketed," says Prof Marie Hicks, an expert on technology and gender.

"There are still an awful lot of adverts that show women… but you do start to see ads coming in. They started showing computer man, they started saying 'do you have good men to run your computer installation?'"

If the secretary was on the way out, the IT helpdesk was on the way in. Now about one in five of those who work with computers are women.

Computers are so clever that it sometimes feels as if they do our thinking for us.

Thanks to Microsoft Word, I no longer think first then write. I do it the stupid way - I write first then think (if needed) later.

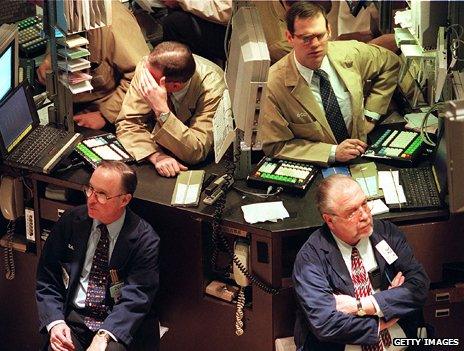

Wall Street was quick to capitalise on spreadsheet technology

Even more impressively, spreadsheet software has made every humble analyst into a near genius. This breakthrough was made in the late 1970s by Dan Bricklin and Bob Frankston with a product called VisiCalc. Its beauty was that it enabled instant recalculation of a whole line of sums just by changing one number.

VisiCalc was seized on by Wall Street - mergers and acquisitions became child's play and financial analysis moved to an entirely new level.

We take spreadsheets for granted now. They've been great. But they've also been a catastrophe. It was spreadsheets that enabled all that too-clever-by-half impenetrable financial wizardry. And we all know where that got us.

Even more of a mixed blessing was an invention in 1985 by a couple of Americans who worked out how to put graphs, bullet points and flow charts onto slides.

Presenter, it was called. Two years later it was sold to Microsoft for less than $30m, renamed PowerPoint and now any old fool with nothing interesting to say can do a bit of cutting and pasting and give an interminable presentation. And they do. All the time. Everywhere.

There is a political party in Switzerland devoted to turning the clock back on this piece of software, which it claims costs 110bn euros a year in lost productivity.

A better way of doing it? The flip chart. In other words, paper.

This piece is based on an edited transcript of Lucy Kellaway's History of Office Life, produced by Russell Finch, of Somethin' Else, for Radio 4. Episode 10, The Office Is Where We Are, is broadcast at 13:45 BST on 2 August