Twin DNA test: Why identical criminals may no longer be safe

- Published

It's well known that identical twins are not totally identical - they can, usually, be told apart, after all. But up to now it has been almost impossible to distinguish their DNA. It's claimed that a new test can do it quickly and affordably, however - and this could help police solve a number of crimes.

At the end of 2012, six women were raped in Marseille, in the south of France. Evidence, including DNA, led police to not one, but two suspects - identical twins Elwin and Yohan. Their surname was not revealed. When asked to identify the attacker, victims recognised the twins but couldn't say which one had assaulted them.

Police are struggling to work out which one to prosecute. They have been holding the brothers in custody since February - each twin says he didn't carry out the attacks, but neither is blaming the other.

When the twins were arrested, media reports said tests to determine who to charge with the crimes would be prohibitively expensive, but that looks set to change. Scientists specialising in genomic research at the Eurofins laboratory in Ebersberg, Germany, say they can now help in cases like this.

"The human genome consists of a three-billion-letter code," says Georg Gradl, their next-generation sequencing expert. "If the body is growing, or an embryo is developing, then all the three billion letters have to be copied.

"During this copying process in the body there are 'typos' happening," says Gradl, referring to slight mutations.

In standard DNA tests only a tiny fraction of the code is analysed - enough to differentiate between two average people, but not identical twins.

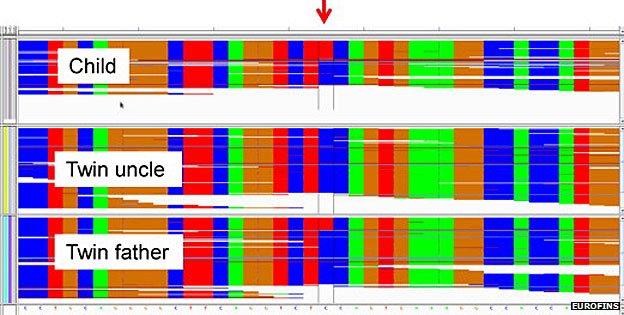

Gradl and his team took samples from a pair of male twins and looked at the entire three-billion-letter sequence, and they found a few dozen differences in their DNA.

The scientists also tested the son of one of the men, and found he had inherited five of the mutations from his father. Having analysed the results, they are confident that they can now tell any twin from another, and from their children.

Results from Eurofins, showing one of the mutations

And the speed of the test is important - it can be carried out in about a month.

Forensic institutes and police from Europe, Latin America and the US have already asked Eurofins if it can help them solve some 10 different cases.

Gradl says cases of rape or sexual violence involving a twin are "more frequent than we expected". Often there are traces of sperm "and in these cases we can really differentiate," he says.

The company can't reveal which cases it is working on, but Gradl admits Marseille is "certainly one of the cases that we would like to help… and we are very convinced that we would get [a result]".

A number of other cases present similar difficulties.

A court in Argentina recently suspended a trial so further investigations could be carried out, after a man charged with rape blamed his twin.

There have also been a handful of cases in the US. Sometimes a tattoo or an alibi has enabled investigators to work out which twin to prosecute, but there have been times when both suspects have walked free.

One of these cases occurred in 1999 in Grand Rapids, Michigan, when a female student was hit over the head and raped.

Five years later, police matched DNA from the attack to Jerome Cooper - but he has an identical twin, Tyrone. Both brothers already had records for sexual assault.

"Both gave us statements, both denied it," says Captain Jeffrey Hertel of Grand Rapids Police Department. "We were naively hopeful that one of them would come forward and say, 'I don't want my brother falsely accused of something - it was me,' but that never happened."

Tyrone Cooper (left) and Jerome Cooper (right)

"At one time we put them in the same room together to see if they would come to some type of conclusion between the two of them. That didn't occur - they just talked small talk," he says.

"We're all hoping that science is going to catch up to this case… we've taken deep breaths, we know it's going to happen, it's just a matter of time."

More than a decade after the assault, he says the victim is "still waiting for her day in court".

Another case occurred in 2009, in Malaysia, when police in Kuala Lumpur stopped a car containing 166kg (366lbs) of cannabis and 1.7kg (3.7lbs) of raw opium, and arrested the driver.

A little later another man arrived at the house to which the car had been heading. They arrested him too. It turned out they had picked up identical twins, Sathis and Sabarish Raj.

Only the first one had a key to the house and would have known for sure what was in the bags in the car.

But when the case came to court, there was reasonable doubt which twin was which. A DNA test that might usually have been able to link a suspect to the car was of no use.

"I can't be sending the wrong person to the gallows," said the judge, according to the New Straits Times.

So both walked free, escaping the death penalty that is mandatory for convicted drugs traffickers in Malaysia.

It's not just crimes that could be solved by the new test - doubts about paternity could also be laid to rest.

In 2007, a court in Missouri heard a case concerning Holly Marie Adams, who had sex with identical twin brothers and subsequently gave birth to a child.

A DNA test gave a nonsensical result - there was a 99.9% probability that Raymon Miller was the father, and also a 99.9% probability that his twin, Richard Miller, was the father.

In the end, the judge had to rely on Adams' testimony to find out the exact dates she had slept with each man, how this corresponded with her menstrual cycle and whether either had used a condom.

In the end he ruled that Raymon was the legal father. The standard of proof was lower than in a criminal trial.

For all of these scenarios, Eurofins' test offers "a very exciting development… a significant step forward in forensic DNA analysis," says Laura Walton-Williams of the Forensic and Crime Science Department at Staffordshire University in the UK.

She says she could also imagine a situation where police would use the test to determine whether a twin had been involved in the murder of an identical sibling - as for the first time they could differentiate between the DNA of the victim and the suspect.

Walton-Williams cautions, however, that courts will want to know how rigorously the method has been tested before they allow it to be used as evidence. The cost of the test will also influence how widely it will be used, she says - and it will therefore probably be used more often in criminal trials than paternity cases, she predicts.

Eurofins won't say publicly how much their test costs

Other companies have said they can do something similar in the past, but for one reason or another it has never proved to be the breakthrough that police and prosecutors need.

And there will always be some cases where no DNA test would be sufficient.

In 2009, jewellery with a retail value of six million euros ($8.2m) was stolen from Berlin's KaDeWe department store.

Traces of DNA were found in a glove found at the crime scene, and once again the DNA led police to twin brothers, who walked free.

But even if police had been able to tell which one the DNA belonged to, they still might not have been able to get a conviction.

The defence could have argued that even though the suspect had once worn the glove, someone else might have left it at the crime scene, and that neither of the twins was ever at the department store.

Georg Gradl spoke to Newshour on the BBC World Service.

Follow @BBCNewsMagazine, external on Twitter and on Facebook, external