The river where swimming lessons can be a health hazard

- Published

The monsoon is about to come to Varanasi, India's ancient city on the Ganges, putting an end to the daily swimming lessons held in the river after school. The children will miss the cooling water, but some experts say it is so polluted the lessons should never be allowed at all.

Hundreds of children take the swimming lessons every summer, from April into the rainy season, in addition to the thousands who wash or bathe in the holy river at other times of day.

But all those who enter the water encounter a range of pollution - including sewage, industrial waste and the remains of partially cremated bodies.

The river's holy status seems to cause parents to close their eyes to the problem.

Talking to mothers watching their children from the bank, cheering as they jump and flap in their fluorescent caps and orange arm pads, you get used to hearing the words: "Mother Ganges cannot be polluted."

"We are people from a holy city. Nothing happens to us when we go into the water," says Namita Tiwari, mother of a 13-year-old swimming in the river below.

A trainer at the Saraswati Swimming Association - one of two clubs that run the classes - even sings the praises of the water sometimes gulped down accidentally by young swimmers.

"The water is unique," says Pramod Sahni. "Once you drink you want to drink again." He drinks it himself while coaching.

In the Hindu faith, the river Ganges is a goddess and its waters are thought to be purifying. But science suggests otherwise.

Some 300 million litres of untreated domestic sewage are dumped into the river every day. In Varanasi itself, a city of a million people, 35 drains and sewers empty into its waters, two of them just a few kilometres upstream from the swimming classes.

This may partly explain why one test by the Sankat Mochan Foundation (SMF), which lobbies for the river to be cleaned up, found levels of faecal coliform bacteria that were 35 times the maximum permissible figure set by the National River Conservation Directorate, 175 times the desirable level - and 440 times the maximum level recommended for swimming in the US.

Untreated sewage from open drains flows directly into the Ganges

Then there are the cremations. According to the Hindu faith, anyone cremated in Varanasi is freed from the cycle of life and death if part of their cremated body is placed in the river as an offering.

It's estimated that 32,000 bodies are cremated every year at two sites in Varanasi - Manikarnina and HarishChandra - and the latter is upstream from the swimming clubs.

The corpses of the poor and homeless, who cannot afford a proper cremation, are dumped in the river too.

It all adds to the risk of waterborne disease.

Natural defence

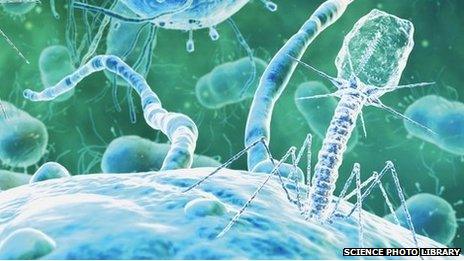

Ernest Hanbury Hankin, a British bacteriologist working in India, reported in 1896 that the waters of the Ganges appeared to have an antibacterial action against cholera. This was later ascribed to a virus known as a bacteriophage (literally, a bacteria-eater).

A scientist at Banaras Hindu University, Dr Gopal Nath, says children are worst affected by bacterial infections during their first year of swimming in the river. Once bacteriophages are present in their intestines, he says, this gives them a "natural immunity".

Industrial effluents, meanwhile, from the city's growing number of factories, include the harmful heavy metals lead, cadmium and chromium.

One of the young girls waiting for her lesson to begin tells me that swimming in the Ganges is "one of the best things about summer", and the river certainly provides relief from the scorching heat.

But some of the children acknowledge that the water isn't perfect.

It looks "green and cloudy" says five-year-old Rishi Mukherjee, who says that he often ends up swallowing a mouthful or two during one of his exercises, which consists of holding his breath under water for as long as he can.

Deep Ganguly, aged 10, says the water "smells fishy".

Last year he suffered from a fever, which his doctor blamed on the river. Other parents talk about children suffering from diarrhoea, or allergies affecting their eyes. But many don't seem to grasp that the holy river could be a risk to their health.

During the summer and monsoon, hospital wards teem with children who need treatment for waterborne diseases - but according to Dr SC Singh, a paediatrician at Varanasi's Shiv Prasad Gupta Hospital, their parents rarely mention that they have been swimming in the river. They don't appear to have made the connection, he says.

The Indian government launched an effort to clean up the Ganges nearly 30 years ago, but with limited results. One problem is that increasing amounts of water have been taken out of the river upstream, for various reasons, reducing the flow in Varanasi.

Contamination can no longer be "washed away" says BD Tripathi, a member of the National Ganga River Basin Authority.

It also doesn't help that the safest place to swim - within 15m of the bank, away from the dangerous currents in deeper water - is also the most polluted part of the river.

Once the monsoon starts, there is no part of the river that is safe for swimming lessons.

Dr Biswhambat Mishra of the lobby group SMF wants to give parents who may be thinking about enrolling their children in swimming lessons next year some clear advice.

They may think there is nothing unhealthy about the water, but there is.

"It is not just unsafe," he says. "It is dangerous to bathe in these waters."

Photographs by Paromita Chatterjee/Agency Genesis

Subscribe to the BBC News Magazine's email newsletter to get articles sent to your inbox.