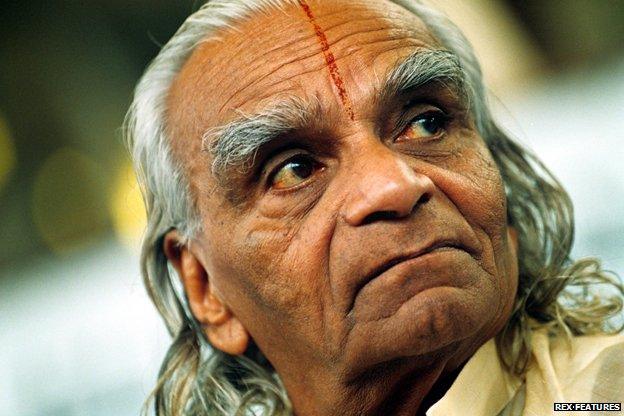

BKS Iyengar: The man who helped bring yoga to the West

- Published

The man widely credited with popularising yoga in the West has died. How did an Indian boy born into disease and poverty grow up to transform the way the world keeps fit?

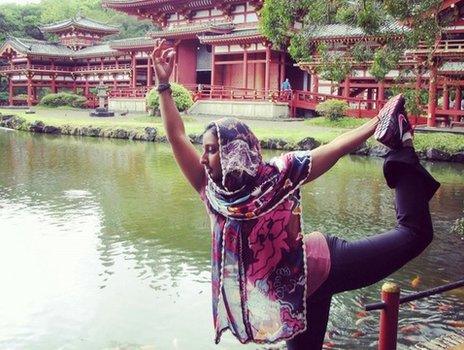

Right now, on exercise mats and in gym classes across Europe, North America and beyond, countless people who couldn't tell you the first thing about Hindu or Buddhist spirituality are stretching, squatting and concentrating on their breathing.

BKS Iyengar, who has died at the age of 95, was credited by many with helping make this happen. In 2002, the New York Times suggested:, external "Perhaps no one has done more than Mr Iyengar to bring yoga to the West."

His own Iyengar yoga system was a global phenomenon, followed by millions. His books were sold in 70 countries and translated into 13 languages. Celebrities like violinist Yehudi Menuhin and author Aldous Huxley feted him. In 2004 he was named one of the 100 most influential people in the world by Time magazine.

David Attenborough pictured with Iyengar (centre) and Menuhin (right) for a 1963 BBC programme

"He had a great influence on, I would suspect, every yoga teacher there is," says Chrissie Harrison, chair of the British Wheel of Yoga.

But he was an unlikely candidate for reshaping the world's workout regime. His poverty-racked childhood in Karnataka was plagued by typhoid, malaria, influenza, typhoid and tuberculosis. Doctors predicted he would not live past 20.

His achievements were the result of his tenacious character, his incredible physical suppleness - television viewers would marvel at the contortions he was capable of pulling - and his ability to connect with people who were capable of promoting him.

After being introduced to yoga at the age of 16, it took the young man named Bellur Krishnamachar Sundararaja Iyengar six years to fully regain his health, by his own account. His body had lost all its elasticity from the time he had spent convalescing in bed.

He said he was so poor that he survived on rice and water for long stretches. He would travel around Indian villages giving yoga demonstrations.

Archive shows BKS Iyengar in the 1930s

His big break came in 1952 when Menuhin heard about his reputation as a teacher during a visit to Bombay and summoned him to a five-minute meeting. That encounter ended up lasting five hours.

The violinist credited Iyengar with improving his playing and helping him cope with his stage fright. Menuhin brought Iyengar with him to Switzerland and then to London, where he was introduced to other musicians.

One of Iyengar's pupils knew Gerald Yorke, a reader with the publishers Allen and Unwin, and showed him the manuscript for the teacher's book Light on Yoga, which set out instructions for more than 200 asanas or postures.

Yorke published the book in 1966. It became a bestseller and has not been out of print since.

What is Iyengar yoga?

Form of Hatha yoga created by BKS Iyengar

Brought to the West in the 1950s when Iyengar started to work with violinist Yehudi Menuhin

Iyengar used around 50 props, including ropes, mats, blocks and chairs to align and stretch the body

Iyengar yoga is now taught in more than 70 countries and the guru's books have been translated into 13 languages

Other well-known yoga practitioners were active around the same time, "but not in the same way and not with such a systemic and rigorous attention to detail in the postures", says the Open University's Suzanne Newcombe, who has researched the development of modern yoga.

Iyengar's method was a form of Hatha yoga. It was, he said, a mixture of art and science. He focused on the physical side of the discipline, emphasising asanas and breath control. He pioneered the use of props like cushions, blocks and benches.

Some traditionalist critics complained he did not do enough to promote the spiritual side of yoga.

Yoga teacher Varuna Shunglu: "He transformed yoga"

"His defence was that yoga was more than just a physical practice but that physical practice offered a gateway," Newcombe says. "He had a very non-dogmatic approach. "In later years he worked much harder to promote a more spiritual approach, but he didn't want to tell people what the content of their spiritual beliefs should be."

This emphasis on health promotion and precision in the physical performance of postures served him well. Because of his secular approach, it was stipulated in 1969 that only the Iyengar yoga could be taught on Inner London Education Authority premises.

He was becoming something of a celebrity. He would appear on television performing feats of contortion. In 1973, when he visited the United States for the second time, there were hundreds waiting for him. Iyengar yoga associations sprung up across North America, Europe and beyond.

But he did not abandon his ascetic lifestyle. A strict vegetarian, he was still practising asanas for three hours a day at the age of 90.

More from the Magazine

For many people, the main concern in a yoga class is whether they are breathing correctly or their legs are aligned. But for others, there are lingering doubts about whether they should be there at all, or whether they are betraying their religion, writes William Kremer.

"Practice is my feast," he told the New York Times.

Many of his students found him "a bit of a drill sergeant", says Newcombe. Some joked that BKS stood for "bang, kick and slap".

He never remarried after the death of his wife Ramamani when she was 46. His yoga school in Pune, Maharashtra, was named after her. Their son and daughter, Prashant and Geeta, were the principal teachers.

Some claims about his influence underestimate the interest there was in Indian culture around the time Iyengar yoga took off around the world, says Newcombe. Many people in the West were clearly receptive to Eastern teachings around the time that Light on Yoga was first published.

But his role in popularising yoga remains hugely significant.

"His legacy is more about the way in which yoga is part of our culture," Newcombe adds. "You don't think there's anything strange about your colleague going to a yoga class after work. Without BKS it might still be very much a fringe thing."

Subscribe to the BBC News Magazine's email newsletter to get articles sent to your inbox.