A Point of View: Should love be symbolised by a lock?

- Published

The "love locks" on a Parisian bridge are meant to represent lovers' undying devotion to each other, but is a shackle an appropriate symbol for love, asks Adam Gopnik.

I am back in Paris, a city I love, where one of my children was raised and the other one born, and to which I sometimes feel I have an almost too professional amorous relation. I mean by that that people assume, knowing that I lived here and wrote a book about it, that I must return to Paris with the theme of An American In Paris playing somewhere in the background and hearty waiters trilling "Sacre bleu!" as they pop open bottles of pink champagne. In truth I meander back in a state of advanced melancholia, and clack my heels on the narrow streets in an unsmiling state, wreathed in a raincoat.

Not that Paris is melancholy - well, actually, it is. The gray drizzle and implacable violet skies of Paris in fall and winter remind us that the impressionists, with their bright dappled light, were first of all fable makers - surrealists. The heroes of Parisian literature all clack their heels, unsmiling, in raincoats on the narrow streets, from Inspector Maigret to Camus. But in my case, at least, something is added - an over-abundance of emotion, a surplus of the heart that has nowhere useful to be delivered or relieved. Even when I am here simply to report a story for a magazine, as I am this week, I feel it.

Paris is a memory-rich place for many - and I am among the many. The girl who became my wife ran away with me to Paris when we were still teenagers, shared a little room in a hotel called, of all things, the "Welcome", the Hotel Welcome, just like that, and swore to come back some day. We did, and when we did, 15 years later, two of the most significant things that I think can happen in life (well, after first love in a hotel room) happened to us here.

The first big thing is to watch an infant become a child - to see a tiny consciousness become a distinct, entire human being with a tongue and an articulate imagination and an original point of view. And then, the complement to that big thing occurs when those who were happy as lovers, somehow have to learn to become parents. When once, not long before, you were a boat out on a sea, still watched, perhaps, by a parental eye from a distance, now overnight you become a harbour yourself, with a life-defining responsibility to a new boat, out on its own voyage.

All those perfect, painful things happened to me here, and when I walk the streets, I feel them all again. I still push my son home in his push chair from the Luxembourg Gardens, see my wife at the corner window nursing our baby and waiting for us to come home - and, belonging as they do to the past, and yet being still so present in my heart, I find that I have nowhere in particular to place the feelings.

The Luxembourg Gardens, Paris

There are some emotions in life so strong that there is nothing to do save feel them, over and over again - and that is really no good. It is as if there was a lock of love shackled tight around my heart in Paris. I cannot help but feel it beating, overwhelmingly, and yet there is nowhere for that beat to drive me, save backwards. These are happy memories, of course, but being past, still make me somehow inexpressibly sad. (I mentioned this emotion once to Marcel Proust, and he said there might be an idea for a book in it.)

I was lucky, of course, to have big things happen in Paris - it makes for pretty pictures of the past. But in a sense it doesn't matter where it happened - I have equally love-locked memories, and a sense of not having anywhere to put them, in Philadelphia, the American city of my birth, where I passed from infant to boy, as my son did in Paris. And Philadelphia is, more or less, the Manchester of America - meaning no ill will to Manchester, just that it, like Philadelphia, presents less pretty pictures than Paris does.

La vie Parisienne dans The Magazine

I walk in Paris in the past. All I have left to do now productively, freshly, newly in Paris is… buy socks. There's an un-ribbed cotton kind here I like that you can't find in America. I think this is a significant fact - I even encourage my 15-year-old daughter, who likes to write, to someday begin her autobiography right there. She should begin her memoirs, I tell her, with the sentence, "My father went to Paris to buy his socks". Or, more poetically, "My father bought his socks in Paris" or, still more iambically, "In Paris, father bought his socks…" But she gives me a steady, opaque, slightly sickened look at the suggestion, and clearly already has memoir-opening sentence plans of her own, probably also involving her father.

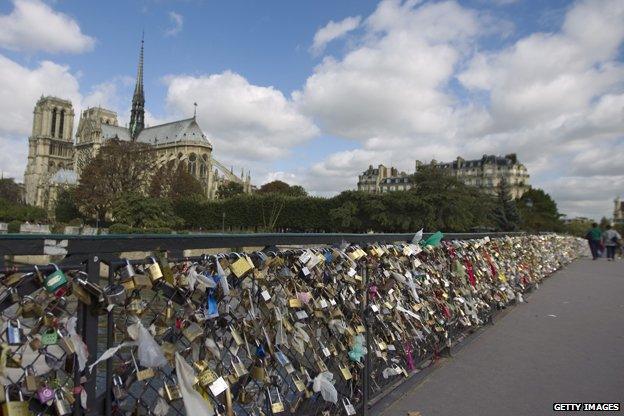

In this melancholy mood, I wandered over just yesterday to a favourite bridge of mine, the Pont Des Arts, to look at - well, to look at the lovelocks. The Pont Des Arts is the footbridge that connects the left bank to right - or rather left bank to the Louvre. These days, the bridge is covered, horribly congealed with, groaning under, another kind of love lock - the small real padlocks people attach to the railings of the bridge, as a sign of their commitment, or at least of their willingness to spend enough on a lock to pretend to be committed. The practice, which I'm sure you've read about, is simple, and by now repeated in the tens of thousands - you buy a padlock, you and your beloved both inscribe your initials on it with a heavy felt pen, you lock it to the bridge - and then fling the key away into the river, indicating that your love will never be unlocked.

Les amants du Pont des Arts

The coming of the lovelocks post-dates my leaving Paris - they began in the mid noughties, I gather. It must have been a touching sight when they first began, and there were only two or three or then five and 10 attached to the bridge's grillwork. They must have provoked a wry smile from a melancholy walker in a raincoat. Now, they are a ghastly, unsightly nuisance. The bridge groans under their collective egotism, their self-centred marking. Unsightly, ugly - they are a form of three-dimensional graffiti, and dangerous too - part of the parapet of the Pont Des Arts collapsed under the weight of the lovelocks earlier this year. So much love assembled together - causing so much public ugliness to be locked in place. Even if one guesses that only one in 10 symbolizes actual love with any chance of ripening into adulthood - even if they were bought only to buy a night in a welcoming Paris hotel with the other signatory - still, what could be better? And yet how unsightly they make the bridges. The overcharge of love is ruining Paris as a place to be a lover.

The City of Paris, engaged in the inevitable argument with the Prefecture of Police and the Ministry of Culture about exactly whose province lovelocks are, has only now begun to do something about them, and that has only made things worse. They have installed sheets of plywood over the thousands of lovelocks, which themselves become sites of graffiti.

Love locks - romantic or wrong-headed?

Lovelocks are so despised by some Parisians that a campaign, No Lovelocks, has been launched. "The delicate Pont des Arts has become a freakish glut of indistinguishable metal lumps, and worse, is now in mortal danger," wrote one of the founders

The sheer weight of locks caused a section of railing on the Pont des Arts to collapse earlier this year, and led to more warnings that the padlocks could prove a menace to passing boats on the Seine

Trend for leaving locks has spread from Paris - in 2007 the Mayor of Rome introduced fines for anyone found leaving padlocks on the Ponte Milvio; meanwhile, padlocks have sprung up in many bridges in the UK, such as Birmingham (pictured)

Are love locks romantic or a menace? (BBC News Online, 5 May)

The full irony of this - that the city of light has to send out the gendarmes to prevent lovers from declaring their love in tangible form - is not lost on anyone. Standing there, appalled by the violence and vulgarity of these affectionate gestures, I recalled Kenneth Clark's famous statement that while one nude is the subject of art, many nudes together are merely naked. The lovelocks are raw, naked too, in that sense.

And I felt, suddenly, then, what I am sure the listener has felt before I could say it: that my own lovelock, this tight tangle of memory and longing, is really just as burdensome to the soul as the lovelocks are to the bridge and to Paris.

For (I thought then) love should never be symbolized by a shackle. Love - real love, good love, love to grow on rather than to be trapped in - is a lock to which the key is always available. Another choice, another day, even perhaps another city, lies out there.

The ugliness of the lovelock lies not in the locks themselves but in the false dramatic gesture that put them there - the key thrown into the water. That kind of love has not really been entrusted to the river. It has merely been abandoned on the bridge.

"I shall buy you a lock," I vowed silently on the bridge in the rain "and you will keep the lock in your pocket while I shall keep the key in mine, and together we would choose, every day, never to need it. Love enchained is what we dream of, but love unlocked is what we need," I added, trailing into blank verse again, as Parisian bridge epiphanies make one do.

So I said to myself - or rather, spoke, unheard, to my wife of so many years, at home now, far away from the scene of our first love, caring for our children - and then I resumed my melancholy Parisian walk, feeling at least, momentarily, liberated. And then I went and bought new socks, which I am wearing as I write.

A Point of View is usually broadcast on Fridays on Radio 4 at 20:50 BST and repeated Sundays, 08:50 BST - or catch up on BBC iPlayer

Subscribe to the BBC News Magazine's email newsletter to get articles sent to your inbox.