A Point of View: Are we really interested in saving time?

- Published

A new food substitute has been advertised as time-saving. But when we say we want to save time, is this a lie we tell ourselves to mask other desires, asks John Gray.

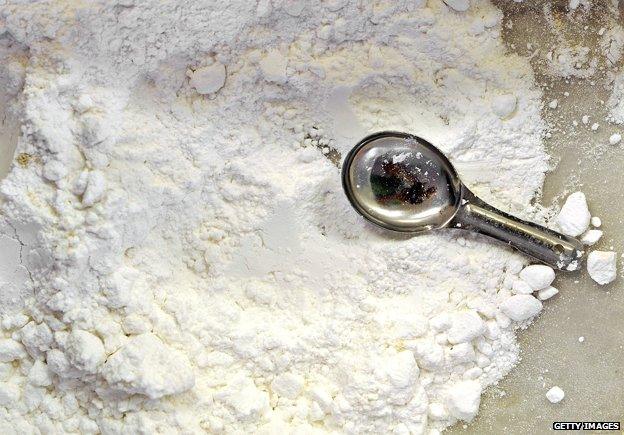

It might seem an extreme step to give up eating meals in order to save time, but this is how a new food substitute is being promoted. Soylent is a drink made by adding oil and water to a specially prepared powder that the manufacturers claim contains all the nutrients the human body needs. It's described as creamy and faintly sweet-tasting, and enthusiasts who have given up regular meals to live on the fluid say it's quite satisfying. With a month's supply costing around £40, it's cheaper than ordinary food and if it becomes widely popular will be even cheaper in future. The suggestion is that you can give your body the nourishment it needs without thought or bother, just by knocking back a drink of the fluid two or three times a day. Invented by a 24-year old American software engineer, Soylent is being promoted as a solution to what many people like to think is the bane of their lives - a perpetual shortage of time.

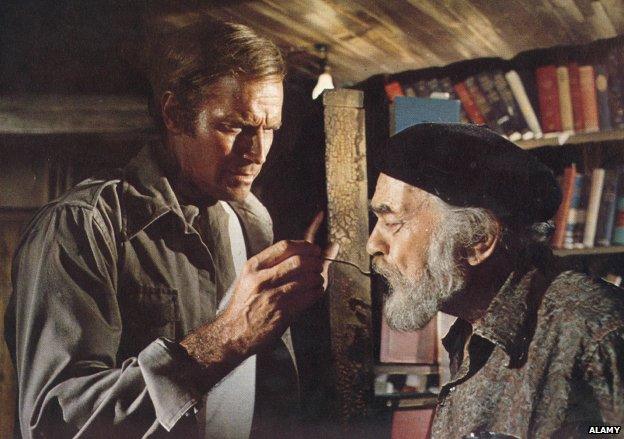

The name of the new food has a curious history. In Soylent Green, an unsettling film that appeared in 1973, the Soylent in question was a green wafer supposedly made from plankton algae. Taking its theme from a novel Make Room! Make Room!, published by the American science fiction writer Harry Harrison in 1966, the film is set in a heavily overpopulated world in which much of humankind lives by consuming the wafer. The action takes place in New York City, by then an overcrowded megalopolis containing 40 million people. The film's story line tells how a New York City Police Department detective investigating a suspicious death eventually discovers that the wafer on which the world's population lives is in fact made from human remains. The film ends with the detective, by now a broken-down figure, exclaiming, "Soylent Green is people!"

Human numbers have greatly increased over the past 40 years - from just under four billion when the film was made to well over seven billion now. At the same time concern about overpopulation, which was widespread when the film was made, has become distinctly unfashionable. Nowadays many would view as heresy the idea that there could be too many human beings on the planet, and I've not come across any mention of overpopulation in the publicity surrounding the Soylent that's being marketed today. The new meal replacement isn't being presented as a remedy for world hunger or an overcrowded planet. It's an affliction of the well-fed that the liquid food is meant to cure.

Charlton Heston and Edward G Robinson in Soylent Green

More than money, Soylent saves time. It's not just preparing, cooking and eating food that you can cut out of your life. You don't have to shop for food or wait to be served in restaurants. Some of those who've experimented with the meal-free lifestyle say it saves them at least an hour every day, effectively adding another day to the week. If like many people you feel you're always harassed and busy, this must seem an enormous benefit. Yet it's far from clear that free time is what consumers of Soylent truly want.

A tub of Soylent

Some critics of the product have focused on what they think are its potential health dangers. We don't know enough about the body's processes, these sceptics say, to be sure that the liquid really does contain everything we need. After all, this isn't a diet that humans have lived on for centuries or millennia. Others have pointed to the loss of pleasure and company that giving up regular food entails. For exponents of what's sometimes called "slow food", meals aren't just a means of fuelling the body. They're occasions when we renew our contact with other human beings while enjoying the taste and variety of local and regional cuisines. From this point of view, giving up traditional foods would be an impoverishment of life.

No doubt there's some truth in these criticisms, but for me they don't get to the root of the matter. Soylent is the ultimate fast food - but it's unclear why we feel such an intense need for more time. If you're struggling to make ends meet, juggling the demands of family and several part-time jobs, you might well dream of having an extra day in the week. But I doubt whether many who are in this position would consider giving up meals in order to work even harder than they already do, and in any case they aren't the people to whom the food replacement is being marketed. It's those that are reasonably well off, and yet think of themselves as being chronically pressured, that are being targeted.

It's worth asking how we've become as time-poor as we feel we are today. I'm old enough to remember discussions of 40 or 50 years ago about how we'd fill our days when most kinds of human labour were done by machines. Technology is largely a succession of time-saving devices. It's strange, then, that an age of unprecedented technological advance should also be one of such acute time-poverty. Are we really dreaming of living more slowly? Or could it be that many of us are secretly addicted to the fast life?

One answer to these questions can be gleaned from the writings of the 17th Century mathematician Blaise Pascal, who invented the modern theory of probability and designed the world's first urban mass transit system. In his Pensees, a series of reflections mostly devoted to religious topics, Pascal suggested that humans are driven by a need for diversion. A life that's always time-pressed might seem a recipe for unhappiness, but in fact the opposite is true. Human beings are much more miserable when they have nothing to do and plenty of time in which to do it. When we're inactive or slow down the pace at which we live, we can't help thinking of features of our lives we'd prefer to forget - above all, the fact that we're going to die. By being always on the move and never leaving ourselves without distraction, we can avoid such disturbing thoughts. That's why, Pascal writes, "We advise people, if they have any time for relaxation, to employ it in amusement, in play, and always to be fully occupied."

Blaise Pascal 1623-1662

French mathematician, physicist, religious philosopher

Established himself early as a gifted mathematician, publishing his first work - on Conic Sections - in 1640

Between 1642 and 1644, Pascal invented a pioneering early calculating device for his tax-collector father

Co-founder of the theory of probability, through his correspondence with Pierre de Fermat

Pascal thought of diversion as a universal human impulse, and I'm inclined to think he was right. What he couldn't have imagined was that an entire economic system would come to be based on catering to this need. Our type of economy can only keep going if it continues to grow, and it grows by inducing us to want to live in the fast lane, always on the look-out for new sensations. But it would be a mistake to think the fast life is somehow being forced on most of us. If you hurry through your days, you don't have time to think. Rather than free time, our true desire may be to avoid reflecting on our actual condition.

Marketing Soylent as a time-saving device was a stroke of advertising genius. No doubt there will be some who take up the meal-free life in order to enjoy the unoccupied space it creates in their lives. Less busy than before, they can use the extra hours to read, meet friends and stroll calmly through their days. But this, I suspect, will be a small minority. For most, Soylent will be a way of squeezing ever more distractions into their lives.

We're reluctant to admit the fact, but for many of us being short of time isn't such a heavy burden. It's having time on our hands that we dread. That's why a product like Soylent has such a bright future. When we give up meals for quick slugs of liquid fuel, we think it's time we're saving. What we're really doing is saving ourselves from too much thought.

Subscribe to the BBC News Magazine's email newsletter to get articles sent to your inbox.