Just how important is Magna Carta 800 years on?

- Published

This year people in the UK, US, Canada, Australia, New Zealand and plenty of other nations will mark the 800th anniversary of Magna Carta. The document will be lauded for establishing one vital principle.

A new book about Magna Carta is published today which claims to offer new insights into one of the most famous documents in British history.

This year marks the 800th anniversary of the charter's first signing on 15 June 1215 at Runnymede on the banks of the Thames between Windsor and Staines.

The book by David Carpenter, professor of medieval history at King's College, London, contains a new translation of Magna Carta and more than 500 pages of historical background and commentary.

The charter was agreed between King John and a group of leading barons, led by Robert fitzWalter, exasperated at the king's arbitrary rule and high taxes. It was in effect a peace treaty designed to head off armed conflict. It failed.

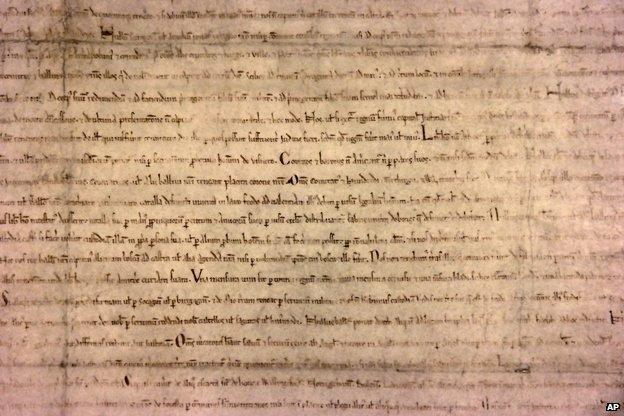

Much of Magna Carta is impenetrable to modern readers, couched in medieval jargon and concerned with the detail of relations between the king and his most powerful feudal tenants. And the charter's most significant innovation, a "security clause" in which the king was subjected to the oversight of a panel of 25 barons, proved impossible to implement.

But the document quickly gained a central place in English political life and remains a touchstone of English liberties. However, few of us have actually read it.

This year's anniversary will be widely celebrated. Melvyn Bragg will present a four-part series on Radio 4 this month, and David Starkey will front a BBC Two documentary. On BBC Three you can watch Magna Carta 2.0, "a new documentary packed full of stunts, fun and comedy" and CBBC is offering a Horrible Histories on King John and Magna Carta.

What was Magna Carta?

Magna Carta outlined basic rights with the principle that no-one was above the law, including the king

It charted the right to a fair trial, and limits on taxation without representation

It inspired a number of other documents, including the US Constitution and the Universal Declaration of Human Rights

Only three clauses are still valid - the one guaranteeing the liberties of the English Church; the clause confirming the privileges of the City of London and other towns; and the clause that states that no free man shall be imprisoned without the lawful judgement of his equals

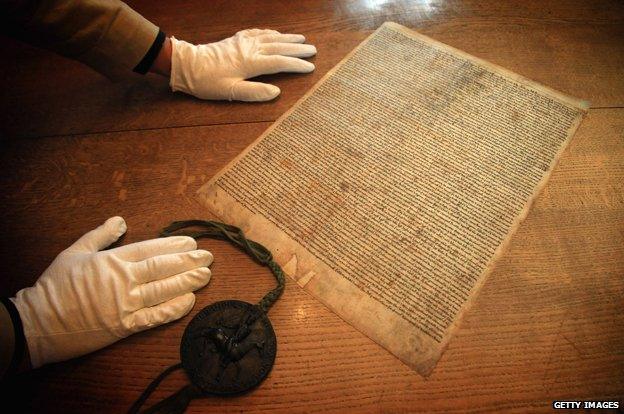

The British Library has two copies of the 1215 Magna Carta

One original copy is owned by Lincoln Cathedral (pictured) and one by Salisbury Cathedral

A deputation of 800 American lawyers will be visiting Runnymede, there is a new Magna Carta cycle trail, an audio-visual display will tour Kent towns with Magna Carta associations, like Faversham and Rochester, and a new work has been commissioned from the artist Cornelia Parker.

The small Hampshire town of Odiham, which claims to be where John stayed before setting out for the negotiations at Runnymede, is getting in on the act with a Magna Carta Festival including a hog roast, morris dancing and a specially-commissioned church anthem with words by John's Archbishop of Canterbury, Stephen Langton, who played a key role in the drafting of the charter.

Magna Carta: Much of it is impenetrable to modern readers

And there will be numerous exhibitions at museums, libraries and cathedrals of medieval manuscripts of Magna Carta. You'll be able to see four examples at the Bodleian Library in Oxford, three on display in Durham and three at the Society of Antiquaries in London.

Most significant of all, in Salisbury, Lincoln and at the British Library there will be displays of the four surviving parchment copies (or "engrossments") of the original 1215 version, issued under King John's own seal. And in February the British Library will be bringing all four together. Just 1,215 people, chosen by ballot, will be able to see them.

David Carpenter's new book for the first time identifies one of the two British Library copies as the one originally sent to Canterbury Cathedral. He also uses recently identified drafts of the charter (they were previously thought to be unofficial copies of the final authorised version) to trace the way the text changed during five days of negotiations at Runnymede.

And he claims that Magna Carta guaranteed Scotland's survival as an independent state by reversing efforts by John to assert feudal overlordship of the kingdom.

The Magna Carta memorial at Runnymede

In 1209 John had forced on William the Lion, King of Scots, a treaty at Norham whose text has been lost. Carpenter believes he has found a 14th Century document in the National Archives at Kew which preserves the terms of the treaty. In it, according to Carpenter's interpretation, William promises that his son Alexander will do homage to John not just for the lands (including the earldom of Huntingdon) which William held in England but for Scotland itself. Magna Carta, by contrast, spelt out that Alexander was to do homage only for the lands in England.

Famously, within weeks of its signing, Magna Carta was a dead letter. The king disowned it, it was condemned by the Pope, and John found himself at war with his rebellious barons. The following year, 1216, a French army invaded in support of the rebels. Its leader, the French king's son Louis, claimed the English throne.

By then John was a sick man and he died at Newark in October 1216, five days after part of his baggage train was lost while crossing the Wash (the two events were not connected).

That should have been the end of it. But at this nadir of English royal fortunes the charter was resurrected as a last desperate throw by a handful of great lords loyal to John's successor, his nine-year-old son Henry. It was reissued, cutting the ground from under the rebels' feet by effectively conceding their demands. And in May 1217 Louis's army was defeated in a battle at Lincoln.

King John

Born 1166 or 1167 in Oxford, youngest son of Henry II

Came to throne in 1199 after his brother Richard ("Lionheart") died (following an earlier unsuccessful attempt to seize the throne while Richard was imprisoned in Germany)

John's reign was marked by war with France - triggered by his second marriage

War needed finance, and John became increasingly ruthless in levying taxes and exploiting feudal rights; this in turn led to civil discontent and rebellion by English barons

After the barons seized London, John was forced to sign Magna Carta in 1215, but it failed to stop civil war

John died in Newark Castle in 1216 after contracting dysentery in the east of England

Henry III reissued Magna Carta in modified form once again in 1217 and then in 1225 - it was this last version that became the definitive text. It was formally confirmed several more times by Henry and his successor Edward I - even though many of its provisions went rapidly out of date, and often weren't enforced even when they were relevant.

But that didn't matter. Magna Carta's significance was always symbolic rather than practical. According to Carpenter, "its arrival does mark a 'before' and 'after' in English history". For the first time Magna Carta established publicly the principle that the king was subject to the law.

A 1297 copy of Magna Carta, bearing the seal of Edward I

It also led indirectly to the development of a new kind of state, in which the money to govern the country came from taxation agreed by parliament by preventing the king from extracting money from his subjects in arbitrary ways. Magna Carta laid down that the king could not levy taxes "save by the common counsel of our kingdom" and set out how that counsel was to be obtained. Fifty years later England's first parliament was called.

As to all the modern-day brouhaha around the anniversary - that rests particularly on another principle bequeathed by the charter to subsequent generations, a principle fundamental to British law and the law of many other nations, including the United States.

Magna Carta's most famous clauses forbid the king to sell, deny or delay justice, and protect any free man from arbitrary imprisonment "save by the lawful judgement of his peers or by the law of the land".

"Free men" in 1215 accounted for less than half the population - the rest were serfs, to whom the charter did not apply. And "men" meant men - women, except for widows, merit barely a mention in Magna Carta.

But the principle was established. The law could serve as a bulwark against tyranny. And once established, it has never been revoked.

More from the Magazine

Magna Carta is considered by many to represent the foundation of democracy, but has its importance been exaggerated?

Subscribe to the BBC News Magazine's email newsletter to get articles sent to your inbox