Viewpoint: The disappearing property ladder

- Published

Mariella Frostrup has been finding out what the country thinks about housing

Many Britons have been brought up with "getting on the property ladder" as a major life goal. But is the ladder disappearing, asks Mariella Frostrup.

Transport yourself back to the year 1980. You're 25 years old and having a drink with a friend. You mention to him that you're keen to get a foot on the property ladder.

He looks puzzled. "That's an interesting way of putting it," he says. "I've never heard that phrase before." He wouldn't have heard it. The first time "property ladder" appeared in the Times newspaper was the next year, 1981.

Spool forward to the present day. If you're an ordinary 25-year-old in the UK and you had the same conversation with a group of friends, the chances are they'd look at you as if you'd lost touch with reality, or wonder how you'd come into untold riches.

For millions of people under the age of 40 the property ladder has become a snake instead - unsettling and threatening, the very antithesis of the stability and security that a home ought to bring.

We've been through what might turn out to be a strange and exceptional phase in the history of the UK, and that simple phrase, "the property ladder", captures so much about it.

A rung on a ladder isn't an end in itself, it's a means to somewhere else - to a stake in society, to greater wealth, to a bigger, better place in a few years' time. Financial security, a sense of belonging, and aspiration, have all been wrapped up in bricks and mortar. The dream of home ownership has profoundly changed. But what does that mean for us as a society, and what we can reasonably expect politics to do in response?

I was lucky. I come from a generation that rolled a six and, for the most part, landed on a ladder on the property board. I bought my first flat in London when I was 21, and it cost about four times the very ordinary salary I was earning.

In the past few weeks, I've been back to my old place. As I walked around it, I was struck again by the emotional power of a home. There were memories and ghosts in every room.

The flat is unchanged in lots of ways, but transformed in one - today, the young person that I was wouldn't have a chance of buying it. At about £400,000, it costs maybe 15 times the salary I'd be earning in an equivalent job today. That's not just a London problem, something similar would be true in large parts of the country.

The turnaround in the past decade has been dramatic. Ten years ago 59% of 25 to 34 year-olds owned their own home, external in England - now it's 36%. What are they doing instead? They're renting from private landlords - 21% were doing that 10 years ago, now it's 48%.

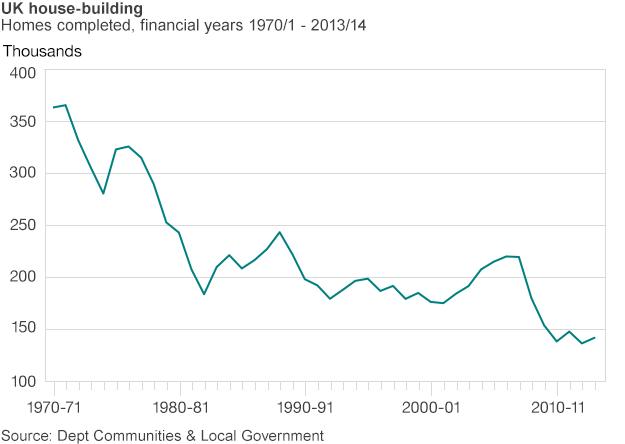

Sometimes, when the world changes this fast, it's not easy to see why, but that's not true of housing. It's simple - we're not building enough new homes, and we haven't done so for years.

And usefully, although we may be short of new homes, we're certainly not short of statistics to describe the problem. It's hard to think of a national failure that's quite as well documented as this one, and here's the scale of it in a nutshell - the UK needs about 245,000 new homes a year to keep pace with demand, and for the past six years the country has built about half that number. We haven't built fewer in peacetime since the 1920s, external.

The problems straddle both homes that are built to be bought, and social housing - housing associations and local councils. Councils have essentially stopped building new homes. Last year in England they built just over 1,000. Meanwhile, on waiting lists for council houses, 1.4 million people were sitting with their fingers crossed.

Overall, the number of affordable homes being built is running at about a third of the 75,000 a year the UK needs.

For people who are renting, the failure to do the big thing - to build enough homes - has led to small policy steps which could add to the growing issue of insecurity.

Governments in recent decades have been keen to get rid of barriers that might deter private landlords, so they've reduced the protection offered to tenants (you're more likely to rent out your place if it's not so difficult to get rid of whoever's living there if you change your mind).

The result may well be that more homes are available for rent, but how secure do you feel living in one? And for those who'd like to see us move towards a German model where the majority of people are in stable, long-term rented homes, the dream seems as elusive as ever.

More from the Magazine

The numbers are stark, but they're not enough on their own to convey the scale of the change we've been undergoing in what housing - a home - means to younger people.

Lord Best has spent a lifetime working in social housing and sums up how things stand: "Everybody under 40 has got some kind of housing problem. They're paying too much for their mortgage, they're paying too much for their rent, they're in trouble one way or the other."

That wasn't true for my generation, and it raises some profound questions for us. How does a country as a whole manage to feel secure when so many of its people are feeling insecure about a fundamental aspect of their lives?

Curiously, while it's not overblown to describe this as a crisis, people are not taking to the barricades about it and politicians can appear surprisingly relaxed. There's been action recently - speeches and policy launches from government, opposition and minor parties - but over the course of many years a visitor from Mars might spot a mismatch between the scale of the problem and the size of the response.

And if that same visitor were to scamper through the history of post-war Britain it wouldn't take her long to identify a single, unavoidable fact - we've only ever built enough houses at times when the state has been involved in building them.

And that presents politicians with a really big choice - are we going to do that again? If we're not, how are we going to meet this urgent need? It's a question that in all the political rhetoric remains unanswered.

What Britain wants

In the early 1970s, New Zealand's Prime Minister Norman Kirk laid out a political philosophy which still resonates today. People, he said, don't want much. They want: "Someone to love, somewhere to live, somewhere to work and something to hope for."

Relationships and a sense of community, a secure home; a secure job, and a belief that life will get better for us and our children - the building blocks of "the good life", but what do they mean today as we grapple with globalisation, austerity, immigration, insecurities and uncertainty about the future? Is the job at hand to work out a new formula for fulfilment or to find a way back to these old certainties?

On the eve of the general election, four Panorama special reports attempt to come up with some answers. Fergal Keane on love, Mariella Frostrup on home, Clive Myrie on work and John Humphrys on hope - all putting Norman Kirk's formula to the 2015 test.

They'll explore what motivates us, how we feel, what we aspire to, what kind of country we want to be.

Fergal Keane: What's love got to do with politics (2 March 2015), external

What Britain Wants - Somewhere To Live will be shown on Panorama at 22:40 GMT on BBC One, 9 March 2015 - or catch up on BBC iPlayer

Subscribe to the BBC News Magazine's email newsletter to get articles sent to your inbox.