Election essay: The town that's used to being disappointed

- Published

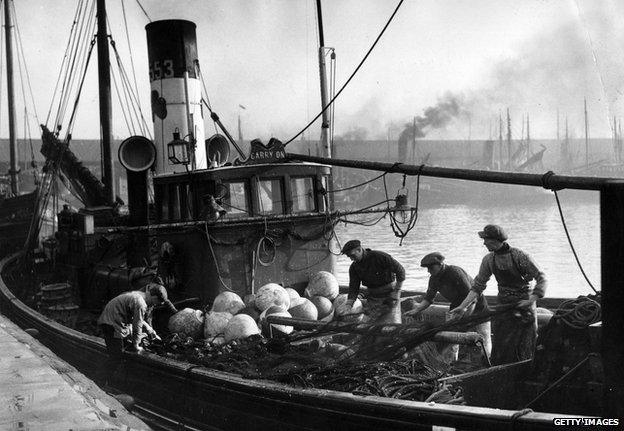

Fishermen are rarer in Lowestoft than fish, one man explains to John Humphrys

Hope is one of the words politicians turn to most, but what do they really mean, asks John Humphrys.

You wouldn't think it sometimes, but politics is all about hope.

It starts that way. The simple fact of voting is optimistic, an act of faith. A person you've never met, and probably never will, makes you some promises.

On that slender basis you decide to support him or her in a bid for a well-paid job in a faraway city, sometimes representing your wishes, sometimes not. That's the deal with MPs. If we weren't used to it, we'd think it was mad.

So politics starts with the hope that promises will be fulfilled, and great politicians understand that those hopes have to be reflected back on the people who put them in office. Bill Clinton shone with hope, never more brightly than when he accepted his nomination as candidate for president, and spoke of turning America into "a country of boundless hopes and endless dreams - a country that once again lifts up its people, and inspires the world... I end tonight where it all began for me - I still believe in a place called Hope."

Bill Clinton, of course, had the slice of luck to be born in a small place called Hope, and the political skill to make the most of it. But what happens when hope fades? I've been to a place called Lowestoft to find out.

It's a tough little fishing town. No one ever had the time to make it pretty - they were too busy hauling in the tons of mackerel and herring that kept people fed, mending the nets, and fixing up the boats. It never had to think about more than a basic education - the jobs on this stretch of coast didn't call for A-levels.

And it didn't have the luck or the foresight to give itself a name that would draw a crowd of tourists. It is the Land's End of the east, but it doesn't have a twin like John O'Groats to make it feel like a glamorous place to end up.

On the face of it, hope is thin on the ground in Lowestoft. The symbols of its decline are smaller, and they've been abandoned more casually, than a pit-head in a South Wales valley or a steel mill in Yorkshire, but they tell the same story.

As you walk around the wooden frames where the great fishing nets used to hang, they speak to you in the same voice as the pits and the mills, but in a whisper - "What was here is gone."

What's left leaves you with an undying impression that hope is at the heart of some of the most fundamental political questions we face.

If you've voted, as often as Lowestoft has, for the party that's gone on to form the government and still been disappointed with what's happened next, if there's no clear answer to the question that hangs like a mist over the town, "what is this place for now the fishing has gone?" and, most of all, if you can see a huge problem in the middle of town that needs political action to fix it, and remains stubbornly un-fixed, why would you believe the promises of politicians? Why would you feel hopeful enough to take that first step of voting?

Up and down this east coast of England, people are asking themselves those same questions and coming up with similar answers. They're turning their backs on traditional politics, the reports say, and looking to UKIP instead. But if you talk to them, the people tell you something different - it's not us turning our backs on politics, politics turned its back on us first.

The huge, un-fixed problem in Lowestoft is a bridge. It goes over the mouth of the harbour but, more importantly, it goes up and down.

Several times a day it's raised to let boats in and out, and every time it goes up it causes chaos. A small town on the farthest-flung fringe of England puts up with traffic jams that some global capitals wouldn't envy.

It can take an hour to drive from one side of town to the other. If there's a better metaphor for the sense of abandonment by politics that Lowestoft feels, the locals can't see it.

The town needs a new bridge, and it's been saying so for 50 years. The people can't afford to build it themselves, and in all that time they haven't persuaded the government to help. Their faith in politics goes down, never up.

When the bridge goes up, Lowestoft grinds to a halt

Unheeded, unrewarded for its skill in picking political winners, unloved by Westminster, Lowestoft ought to feel desolate. It ought to feel hopeless - but it doesn't.

Why? The best answer I've seen came from the American historian Studs Terkel. "Hope has never trickled down," he said. "It has always sprung up."

And from somewhere Lowestoft has found the reserves of hope to keep going. Three of the four schools in the town have been in what's called Special Measures - they've been failing, in other words - but while I was there, one pulled itself out.

Businesses keep starting up, built on the engineering and fishing skills of the past. People never stop trying to make the place better, and if they ever thought they could rely on politicians to do that for them, they don't think so now.

And perhaps it's the awareness that, these days, you have to make your own hope that's been one of the biggest changes in my lifetime. When I came out of school, nobody told me and my classmates that our lives would be better than our parents' lives - that we'd have more money, and many more opportunities - but the truth is that they didn't need to tell us, we just knew. And we were right.

That easy certainty which allowed me and my friends to breeze confidently out into the world isn't in the air any more. The fall of the old industries, the rise of globalisation and the dawn of new technologies have put paid to it. In the end, our kids may be better off than we've been, and they may have more opportunities, but they can't rely on that being the case as I could. They'll have to work hard at it.

Politics will have to adjust too. As the world has changed, power has shifted from West to East, and from parliaments to boardrooms, politicians have sensed their new status and grown wary of over-promising.

They've reined themselves in, made themselves rather smaller in the grand scheme of things. But if they let themselves become too diminished to promise a brighter future, the danger is that we lose our hope in them.

The bonds between us and our MPs are bonds of hope. They've been frayed by tough times in the last decade. If they break, we're in trouble.

Fishermen in the 1950s preparing their nets on board a trawler at Lowestoft.

What Britain wants

In the early 1970s, New Zealand's Prime Minister Norman Kirk laid out a political philosophy which still resonates today. People, he said, don't want much. They want: "Someone to love, somewhere to live, somewhere to work and something to hope for."

Relationships and a sense of community, a secure home; a secure job, and a belief that life will get better for us and our children - the building blocks of "the good life", but what do they mean today as we grapple with globalisation, austerity, immigration, insecurities and uncertainty about the future? Is the job at hand to work out a new formula for fulfilment or to find a way back to these old certainties?

On the eve of the general election, four Panorama special reports have attempted to come up with some answers. Fergal Keane on love, Mariella Frostrup on home, Clive Myrie on work and John Humphrys on hope - all putting Norman Kirk's formula to the 2015 test.

They've explored what motivates us, how we feel, what we aspire to, what kind of country we want to be.

Fergal Keane: What's love got to do with politics (2 March 2015), external

What Britain Wants - Something to Hope For will be shown on Panorama at 20:30 GMT on BBC One, 23 March 2015 - or catch up on BBC iPlayer

Subscribe to the BBC News Magazine's email newsletter to get articles sent to your inbox.