Shakespeare's evolving attitudes towards women

- Published

Marcelle Dupre (centre) played Juliet in a 1996 adaptation for the BBC

If you could take on the role of one woman from Shakespeare's plays, who would it be?

Perhaps the passionate Juliet appeals, a hormone-addled adolescent whom love transforms into a full-blooded woman aware of her sexuality and not afraid to express it.

Could some situations at work call for the dubious talents of Lady Macbeth? (Remembering, of course, that actions have consequences)

Or maybe you'd relish the chance to coach your lover by disguising yourself as a man, following Rosalind's lead in As You Like It.

The choice is as varied as the characters themselves - and Tina Packer knows them all intimately.

An actress and Shakespeare expert, Packer has just published a new book - Women of Will: Following the Feminine in Shakespeare's Plays. It looks at the way Shakespeare developed his female characters, and how his own views of women changed over time.

She says Shakespeare didn't understand women in the beginning of his career.

"I think something happened, somewhere around Love's Labour's Lost and the early history plays and going into Romeo and Juliet. Either he fell in love or he just grew up, but something happened to him where he suddenly 'got it' about women and there was a profound shift in his writing," she says.

"You see it in his first full blown version, in Juliet herself. Through her he began to take on what it meant to be a woman."

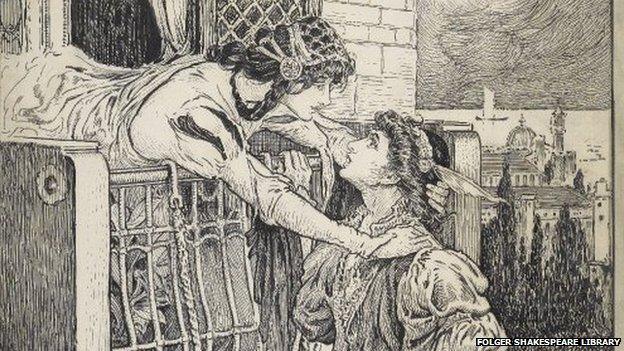

Juliet in the past...

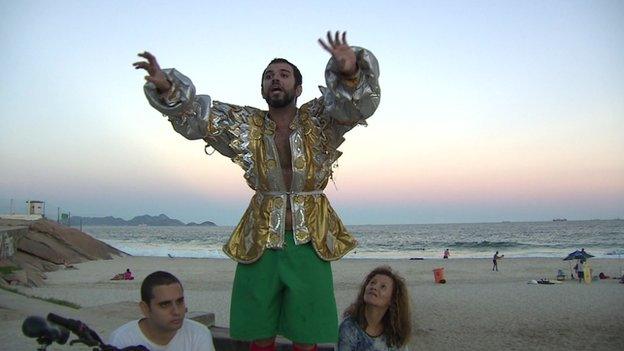

... and Romeo and Juliet as played by Syrian refugees in 2015

Packer reckons it took Shakespeare about three years of professional writing to reach that point.

The change is particularly noticeable when comparing Kate, the unfortunate subject of The Taming of the Shrew, to Beatrice in Much Ado About Nothing.

Both women are being wooed, but while the sparks fly verbally between Beatrice and Benedick, Kate and Petruchio get physical.

"Beatrice and Benedick begin sparring, much like Kate and Petruchio do, but the outcome is so profoundly different," she says.

Tina Packer's book explores how Shakespeare's female characters evolved over the course of his work.

"You feel theirs was a good marriage, but Kate and Petrucio? I don't think so. It was such a horrid way of taming her - starving her, taking away her clothes, not allowing her to say what she thinks and feels. You can't be a whole person if somebody is beating you up in that kind of way."

How Shakespeare's women are perceived depends on contemporary attitudes.

Audiences several centuries ago might have had fewer problems with Kate being forced into submission.

"The popularity of Shakespeare's heroines waxes and wanes according to how they seem to represent certain moments and notions of femininity," says Gail Kern Paster, director emerita at the Folger Shakespeare Library.

"One of the major figures in the 19th Century was Imogen in Cymbeline, who is not very important to us at all. But they thought she was just a remarkable example of feminine constancy."

Imogen incurs her father's displeasure by marrying the man of her choosing.

Imogen was a popular character in the 19th Century - played here by English actress Ellen Terry around 1880

The usual misunderstandings and betrayals take place and Imogen, like so many of Shakespeare's women, resorts to disguising herself as a man.

Throughout it all she remains true to her love and almost everybody lives happily ever after.

"But women now bring to the parts their own sense of independence," says Michael Kahn, artistic director of the Shakespeare Theater Company.

"I have done Measure for Measure maybe four times in my life and the later it is [performed] the more women have to figure out what they do in that last scene and whether they forgive the duke or not."

"In the 19th Century of course the women always forgave the duke."

Mark Rylance played Olivia in Twelfth Night in 2011 at the Globe Theatre. Most female roles in Shakespeare's time would have been played by young boys

Female characters in Shakespeare are often so perceptively drawn that it can be easy to forget that they would have been played by men, or at least young boys.

"So many of the great women's parts like Rosalind [As You Like It] and Viola [Twelfth Night] were based on the fact that they were boys being girls playing boys being women," says Kahn.

"But nobody has ever said to me, a woman wouldn't feel this way or a woman wouldn't do that."

Packer says putting women in trousers also allowed Shakespeare more freedom in creating important roles for them.

"They start becoming the characters in the plays who are telling the truth about what's going on," she says.

A 1908 advert for The Taming of the Shrew, starring Lily Brayton

"If they tell the truth and stay in their frocks, they're killed or they run mad and kill themselves.

"But if they disguise themselves and go underground, they not only can have their voices, they can organise society and it all ends up terribly well," she says.

In some plays, Shakespeare goes "goes into this dark place where the women want the same things as the men".

Rosalind pretends to be a man in As You Like It

"Think of Lady Macbeth, Volumnia in Coriolanus, and the eldest daughters in King Lear. What happens when the women are as ambitious as the men? It's terrible."

Tina Packer says one of her favourite characters is Paulina in The Winter's Tale.

"I love the way she keeps telling the truth, come what may, and is fearless."

Michael Kahn doesn't have a favourite but says he loves Cleopatra, Rosalind and Viola.

Laura Rogers as Lady Macbeth in a 2011 performace

He's also very fond of the Countess in All's Well That Ends Well "because she knows how to get from other people what she wants to find out in an extraordinarily clever way".

And Gail Kern Paster says she likes Rosalind but "definitely wouldn't want to be Desdemona in Othello because he doesn't have a clue."

But all the roles have one thing in common, Paster says.

"Whether they're mothers, ingenues or unruly woman, they are all women discovering how to find their way in the world. And it's a pretty tough world."

- Published12 April 2015

- Published18 March 2015

- Published12 September 2014

- Published21 August 2014