Getting close to my son who died on Air India 182

- Published

Thirty years ago an Air India plane was blown apart by a bomb just off the Irish coast, as it flew from Toronto to Delhi. All 329 on board died, making it the most deadly bomb attack ever on an airliner. For relatives - mostly Canadians of Indian extraction - south-west Ireland remains a place of pilgrimage.

On the morning of Sunday 23 June 1985 Lt Cdr James Robinson of the Irish Naval Service was at sea dealing with a boat that had been fishing illegally, when something caught his ear.

"Normally there's a terrible babble at the back of the bridge but somehow you pick out anything unusual. When a message came over the VHF repeater that a plane had disappeared off screen at Air Traffic Control at Shannon Airport we turned around as fast as we could.

"At first we had no real detail - we could have been dealing with a Cessna for all we knew. On the way the galley was cooking up soup and the sick-bay was prepared, but the journey took almost three hours and before long we knew it was Air India 182 which had disappeared - a Boeing 747 with more than 300 people on board."

A nightmarish scene awaited the crew when they arrived.

"An RAF Nimrod was dropping smoke floats to direct us to anything substantial in the water. There were parts of the plane everywhere. I remember being surprised how even big bits of fuselage and undercarriage and wing could float.

"But the shocking thing was that we were surrounded in the water by dead bodies. I sent out a three-man patrol in an inflatable Gemini craft to collect what bodies we could."

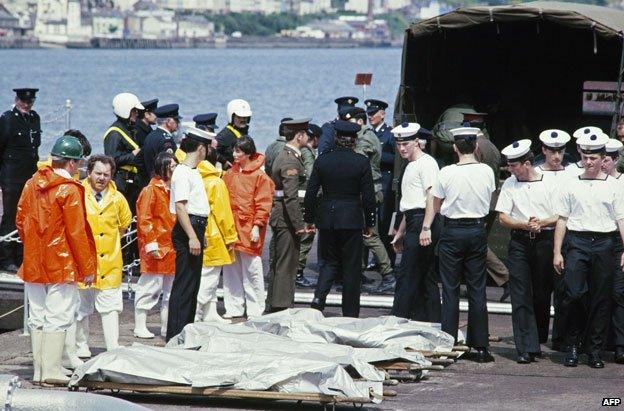

A total of 132 bodies were retrieved - by Robinson's offshore patrol vessel, by merchant vessels and by British RAF and Royal Navy helicopters which joined the search.

Robinson, who was in overall charge, remembers that the operation continued until 11pm. "Both the British and the Irish were courageous in recovering bodies before they sank," he says. "But we knew we weren't looking for survivors."

Air India flight 182 from Toronto to Delhi was destroyed mid-air about 120 miles off the south-west coast of Ireland by a bomb in the suitcase of a man who had checked in a suitcase but had not boarded the flight. The attack was the work of Sikh militants who wanted to strike at the Indian government after the Golden Temple at Amritsar - the most important shrine in Sikhism - was stormed by troops in June 1984.

Some Sikhs wanted an independent homeland and in October 1984 the Indian Prime Minister, Indira Gandhi, was assassinated by her Sikh bodyguards.

The loss, the next year, of Air India 182 remains the most deadly bomb attack on an airliner - and one of the worst air disasters of any kind by number of fatalities. But outside Canada, India and Ireland it is little remembered - particularly after 9/11, which caused so many more casualties on the ground.

The Sheep's Head peninsula in West Cork is the closest you can get on land to the area where flight 182 came down, and a memorial in the tiny village of Ahakista is visited every year by relatives of the dead - more than 20 were expected to attend a 30th anniversary ceremony on Tuesday.

Babu Turlapati and his wife Padmini, who were robbed of both their two children in the atrocity, have made the journey every June since 1986.

"It is the most beautiful and serene of places," says Babu, a retired accountant, who now spends much of his time helping poor children in India. "Padmini and I were desperately sad to come here the first time of course - but the wonderful landscape by the sea and the kind and generous people have been a very big strength for us every year."

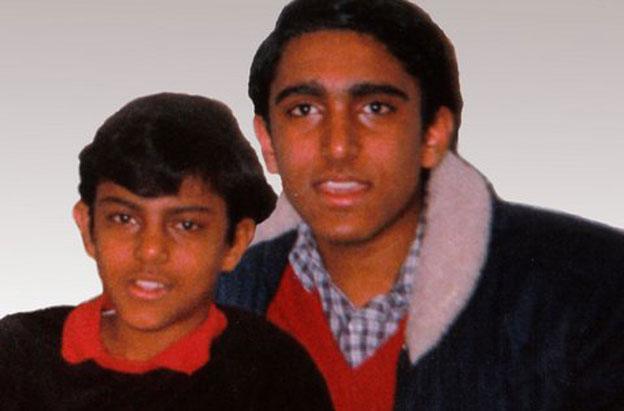

The Turlapatis' children, Deepak and Sanjay, in 1985, aged 11 and 14

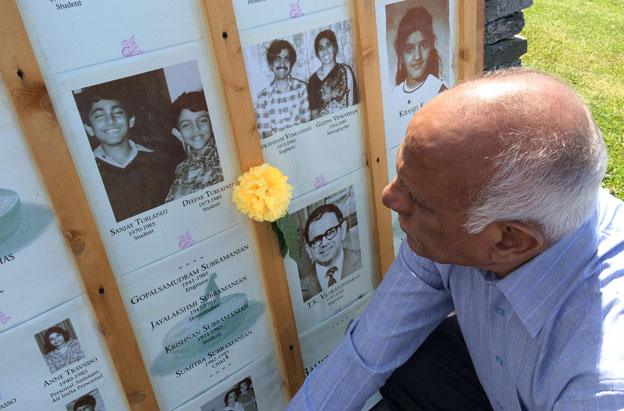

A temporary display for the 30th anniversary includes photographs of those who died

He now looks on the remote peninsula, and the memorial site with its views of Dunmanus Bay and to the Atlantic beyond, as a kind of home.

"When we come back to Ireland everyone from the customs man at the airport to people in the local supermarket say hello to us," says Padmini, a paediatrician from Markham, Ontario.

She still remembers in painful detail the moment when they discovered their two boys, Sanjay and Deepak, had died.

"We were at home sleeping when a phone call came from a friend. My husband took it and he collapsed. He said, 'All is gone.' I had heard him mention news on the BBC so I turned on the television and I found out what had happened. I never cried because I am the strong one.

"As a scientist I knew at once no-one could have survived. But as a mother it is different. Until recently that part of me would come to Ireland each year thinking, 'Well maybe there will be a miracle and the boys will return.'

"When I stand beside these waters I talk to Deepak, whose body lies in the oceans forever. Deepak runs up to me in the waves and he talks in the wind and the rain. He was a naughty and funny 11-year-old and I can feel his presence. This is why we come back each year."

Padmini is bitterly disappointed that the bungled criminal investigation into the bombing resulted in only one person being convicted.

"But what point is there now in anger? What will come of it?" she says. "Everyone accepts the investigation was flawed."

Journalist Kim Bolan of the Vancouver Sun wrote a book about the investigation and the two-year court case that followed. She says there are a number of reasons why things went wrong.

"One reason is bureaucracy. The government had only recently set up the Canadian Security Intelligence Service - roughly the equivalent of MI5 in Britain. That intelligence function had been with the RCMP (Royal Canadian Mounted Police) and some in the RCMP resented the change. At times there was a lack of co-ordination.

"But there was something more basic. Canadian society 30 years ago was different and writing my book I kept thinking how things would have been if the victims had mainly been from white families.

"Naturally Canada was shocked by the explosion - until then we all assumed terrorism happened elsewhere. But at the same time a lot of Canadians felt a disconnect. It wasn't a Canadian plane, most of the victims had Indian names, and the explosion took place over Europe.

"There was a kind of racism at work. It was a Canadian tragedy but people didn't quite see it that way."

It took 25 years for the Canadian government to apologise for the handling of the investigation.

The memorial at Ahakista on the 20th anniversary of the bombing, in 2005

The only man jailed for his role in the attack was Inderjit Singh Reyat, who was arrested in the UK and initially jailed in connection with a second bomb on an Air India aeroplane on the same day - this bomb killed two baggage handlers in Tokyo's Narita airport.

Reyat later pleaded guilty to manslaughter in connection with flight 182.

Two other men, Ajaib Singh Bagri and Ripudaman Malik, were also charged but were acquitted in 2005.

"The only person found guilty may soon be a free man," says Padmini, gazing out over the calm fringe of the Atlantic. "Yet we will suffer our terrible sentence until we die. What did our beautiful sons have to do with an argument over religion and power?"

Normally, she says, she tries not to think of the politics surrounding the loss of Air India 182. It is too upsetting.

The annual visit to Cork is a healing experience, she says.

"I come with all the worries and the pettiness of life and it calms me here. The water has my son in it. It has all the Earth's joys and tears and it replenishes me."

I ask her husband to squat down for a final shot of him looking at his sons' photograph on the display built for this week's ceremony.

It proves too much for a 74-year-old and Babu tumbles on to his side. I apologise for my request.

But Babu Turlapati is laughing. "No problem, no problem at all," he says happily. "It is just Deepak playing a little trick, the way he does."

Subscribe to the BBC News Magazine's email newsletter, external to get articles sent to your inbox.