Eric Roberts: The spy who suffered

- Published

One of the UK's most brilliant wartime spies was poorly treated by colleagues at MI5 in the paranoid years of the Cold War and was left gripped by fear that he was suspected of being a traitor. Now an extraordinary letter and a series of family documents reveal the full story.

In the 1930s, Eric Roberts was a clerk with the Westminster Bank, where he seemed to be an average, unassuming employee.

But Roberts's real work was espionage. He had been a field agent for MI5 since the 1920s, recruited by famous spymaster Maxwell Knight, and infiltrating first communist then fascist groups.

In 1940, when Churchill became concerned about the activities of potential fifth columnists, Roberts was taken on as a full time agent by MI5.

Working under the alias "Jack King", Roberts posed as a Gestapo officer, part of the Einsatzgruppe London. For five years he worked with Nazi sympathisers in Britain, who thought they were part of a "fifth column" ready to help a German invasion.

Through his networks Roberts identified nearly 500 people who had some support for Germany. He would meet his key contacts, log information they gathered and convince them they were working for the Nazi war effort.

It was a difficult and dangerous role , for which he won the admiration of superiors and colleagues. One official file refers to him as a "genius" spy.

"There is no doubt that the information which we obtain from the fifth column organisation is, on the whole accurate. It depends largely on the character of the central agent... he has a very remarkable degree of skill and an equally remarkable memory for details and ability to express himself."

After the War, MI5 brought Roberts into the Office, as it was known.

But a letter Roberts wrote years later to an old colleague - and supplied by his family to the BBC in response to this piece - shows what a different world postwar espionage proved to be.

Eric Roberts with his wife

His work in London, and for a year in Vienna, was overshadowed by anxiety. His letter - from 1969 - recounts how he had tried to warn colleagues about Soviet moles but that his warnings backfired.

Roberts believed he was frozen out - mistrusted and even put under surveillance himself after he'd tried to raise the alarm.

He took early retirement in 1956 at the age of 49. He had already sent his two teenage sons to live in Canada. He followed them, with his wife and young daughter Crista. They drove west across the country - as far from the attention of the Office as they could get - settling on Salt Spring Island, a beautiful spot near Vancouver.

In autumn 1968 a car pulled up outside their modest family home. In eight acres of land it sat high on one of the island's hills - with magnificent views. Two men in suits came to the door. One was a Canadian police officer and the other an Englishman, Barry Russell Jones, from MI5.

Jones had come to talk about Roberts's secret past, especially his time in London after the war. He wanted to ask whether Roberts suspected any colleagues, past or present, of being a Soviet spy.

The flight of double agents Guy Burgess and Donald Maclean to the Soviet Union in 1951, and then Kim Philby's defection in 1963, deeply unsettled the secret services.

The search for double agents continued - even though MI5 had privately identified Anthony Blunt and John Cairncross as belonging to the same spy ring.

"By 1964, MI5 had identified all five of the Cambridge spies, Burgess, Maclean, Philby, Blunt and Cairncross," says Calder Walton, author of Empire of Secrets. "But they couldn't be sure that that was the sum total of the Cambridge Spy Ring or that they had actually got the right people.

"It was a case of the known unknowns and unknown unknowns. It was only with the defection of Oleg Gordievsky, the former KGB double agent, in the early 1980s that they were able to confirm that they had, in fact, got the right people."

Eric at his home in Canada

Roberts had been warned that he was going to receive a visit. He'd already written a name - "Tony" - on a piece of paper and slipped it into an envelope.

He handed it to Barry Russell Jones. Roberts wrote later to a friend that he had originally identified "Tony" as a foreign agent in 1941 - and had tried to warn others about him, only to encounter hostility. Roberts had initially got something wrong - he'd assumed "Tony" was a Nazi agent, given Britain was at war with Germany.

MI5 later told Roberts he was right about "Tony" - almost certainly Anthony Blunt.

There are no notes of the meeting at the Roberts family home in autumn 1968 - but it clearly took some time. While Jones wrote later that he'd found it helpful - it had a traumatic effect on MI5's former "genius" agent.

Roberts wrote to an old friend in MI5 some months later: "For two days after his departure I was OK. Then fear returned in full force. Yes, fear. Barry in the last minutes of our meeting had placed his finger on a most delicate spot. He knew what I knew. Yet I felt at the same time that he had a suspicion I was a Soviet agent."

The visit made Roberts physically ill.

"I had done my level best to forget the Office. Barry brought it all back again and it hurt like hell."

MI5 had asked Roberts to write down anything that might be useful. He sent a long rambling letter - 14 closely typed pages, to Harry Lee, an old friend from his wartime days.

"It's the most extraordinary intelligence document I've ever seen," says Prof Christopher Andrew, author of the Official History of MI5. "It's 14 pages long - it will keep conspiracy theorists going for another 14 years. It's a mixture of fact and fiction and the other thought I have is to be desperately sorry for the individual who wrote it."

Roberts, a grammar school boy who'd gone to work at 17, felt he'd never been accepted by MI5 officers, many of whom had gone to public school and Oxford or Cambridge. He believed that Dick White, head of MI5 from 1953-56 , had attempted to "blackball my entry into what was in effect a rather exclusive club". But Roberts did have many friends from wartime days - notably Guy Liddell, deputy director of MI5 - whom he confided in.

In 1947 Roberts was seconded to Vienna to work with MI6, the Secret Intelligence Service. Before Roberts went, he spoke to Liddell. According to Roberts, Liddell warned him "there was a traitor operating at the highest level" of the SIS.

Roberts arrived in the Vienna of The Third Man - a dangerous city, busy with intelligence agents from all sides. Soviet and Western agents could easily mix. But it was unpredictable and dangerous.

According to Roberts's letter, he was back as an agent in the field - posing as a disaffected British civil servant and passing low-grade harmless information, to a Communist named Jellinek.

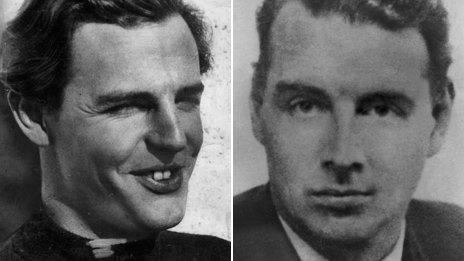

Kim Philby and the Cambridge spies

'Cambridge spies' Donald Maclean and Kim Philby

Harold "Kim" Philby (1912-1988) was one of the most famous spies of the 20th Century; he was recruited by Soviet intelligence while still at Cambridge University, along with fellow students Donald Maclean and Guy Burgess, and the academic Anthony Blunt

Philby rose to become a high-ranking officer in British intelligence during WW2 and the early Cold War, while simultaneously passing British and US secrets to Russia; by 1949 he was Britain's chief intelligence representative in Washington DC

In 1951 Philby tipped off Maclean and Burgess that they were suspected of being Soviet spies; they fled to Russia - Philby was accused of aiding them, but the charge was left unproven; nevertheless it signalled the end of his intelligence career

By 1962, Philby was working as a journalist in Beirut when new evidence of his treachery emerged; he managed to escape to Moscow, where he lived the remainder of his life

Once, the MI6 station chief, George Kennedy Young, wanted Roberts to meet his "star agent" who was "in close contact" with the KGB.

"I refused the offer," writes Roberts in his 1969 letter. "Some weeks later George Y told me rather shamefacedly that the star agent had turned out to be a Soviet agent. His unmasking had been purely accidental. I gave private thanks to Guy L. Without his prior advice - I would have met disaster."

After he'd returned to London, Roberts picked up the question of the traitor with Liddell, asking if he'd been identified. Liddell evaded the question, according to Roberts.

He went on to ask if Roberts had ever thought that MI5 might have been "penetrated" too. Roberts said yes - and went on, when prompted, to describe the "type" of person who might be a Soviet spy. Roberts said it would be "a man who by ability and social acceptability could reach a command position. He must have attended the same schools and universities as the rest of the people in the Office."

He thought the spy would be "inspired" by ideology, not financial gain. Roberts recalled he had said it would be "useless" for a man like himself to attempt the assignment - as his background was so different.

"It was at that point that I made the biggest blunder of my career," Roberts wrote. "I said that if the Soviet agent became a member of one or two of the most exclusive clubs, I doubted if anybody would be willing to entertain doubts of his loyalty."

There is no note in Liddell's diary of such a conversation.

According to Roberts's letter, he felt he'd lost Liddell's trust and that others had become suspicious too. He even believed he was followed by a quartet of trainee agents round London.

In 1956, Roberts was told that "the DG [director general] had decided to dispense with my services". He was told he'd been found "unsuitable for intelligence work". He moved to Canada and did his best to forget.

Harry Lee, at MI5, wrote in response to Roberts's long 1969 letter saying that he was sorry that Jones's visit had caused such a relapse, and that there was no need for him to worry Roberts with any more questions. He assured Roberts that the watchers had never been put on to him - that he had never been under any suspicion.

Roberts's children remember he seemed relieved after this. But it was only when they found the letter after his death that they realised how much turmoil he'd been through. His son Max, now 79, says he was treated badly. "He was a grammar school boy from Cornwall and for him to have said the various things he said about those upscale guys - and not to be believed - that created the tremendous amount of stress he was going through."

Reviewing Roberts's letter, MI5 historian Calder Walton believes it shows the impact of the climate of doubt during the 1950s and 1960s on a fine agent. "It shows the human tragedy of people not being trusted by their apparently close friends within the services."

Andrew believes there's a simpler explanation - that Roberts was ill-suited to a desk job, and was haunted by his wartime glory. "After World War Two he was put on a desk job and it didn't work. And he began to get - obviously - extremely depressed. And when the investigations into Soviet penetration begun he began to think without any reason whatsoever that he was a suspect."

Roberts's daughter Crista, now 73, thinks a simple acknowledgement by his colleagues could have saved her father years of unhappiness.

"I think some recognition from his peers would have gone a long way. Not an OBE or anything like that - just the Office telling him he'd done a really good job. He was a humble man, an unassuming man, but he was very good at his work."

Eric Roberts's story features on Document on Radio 4 at 16:00 BST on Tuesday 14 July or catch up later via iPlayer

Subscribe to the BBC News Magazine's email newsletter to get articles sent to your inbox.

- Published28 February 2014

- Published17 January 2014

- Published26 October 2012