Scientists rush to freeze plant DNA before 'sixth extinction'

- Published

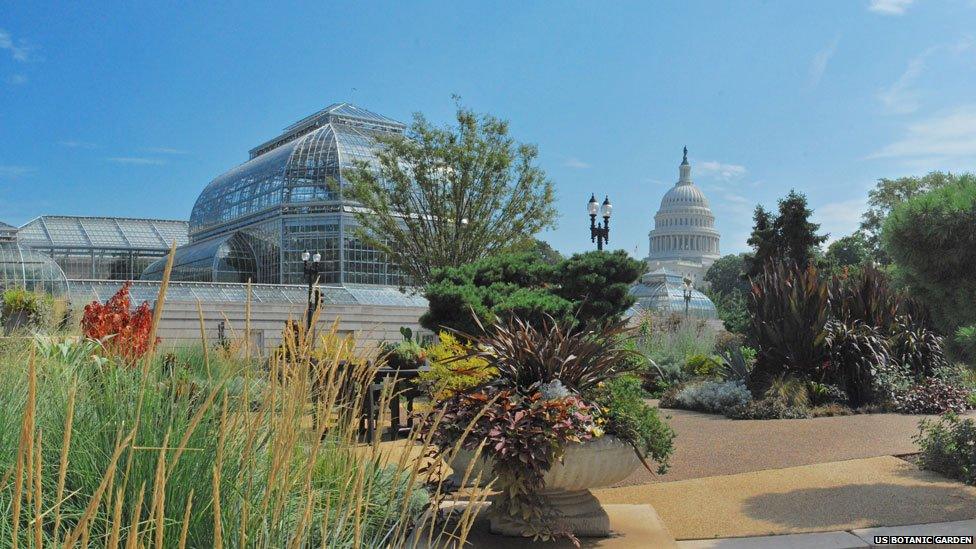

Could these plants be extinct soon? The Global Genome Initiative aims to freeze plant DNA for safekeeping

As the world enters into a sixth great extinction, scientists are racing against the clock to save genetic evidence from plants around the world.

An ambitious project launched Wednesday to collect the genomes of the planet's major plant groups within the next two years and put them into deep freeze.

The project is part of the Global Genome Initiative, which aims to gather and preserve the DNA of all life on Earth in cryo-storage facilities.

The task sounds daunting, but scientists leading the initiative at the Smithsonian's National Museum of Natural History say it will only take a few months to gather samples from half the world's plant families because they're already growing in botanic gardens. Most can be found within a five-mile (8-km) radius of Washington, DC.

There are some 500 plant families and more than 13,000 genera within those groups. The task is urgent because some species are facing extinction. In fact, scientists warn that Earth has entered its sixth mass extinction - the last such event killed the dinosaurs 65 million years ago.

Where the plant DNA will be stored

"It's not just plants - it's plants, animals and micro-organisms," says John Kress, interim Under Secretary for Science at the Smithsonian Institution.

"Everything that is alive and living in a natural habitat is now being threatened by degradation of those habitats primarily because of what we're doing as humans."

He says it's difficult to measure the rate of plant extinction but some scientists have estimated that all species of life are becoming extinct 100 times faster than normal.

The Global Genome Initiative complements ongoing efforts to save the seeds of many plants that are being stored in special vaults around the world.

"Seed banks were set up primarily to preserve the seeds of economically important crops, to keep a living bank of tissue with which we can grow these plants again in the future. The genome project is to preserve the genomic history and content of these plants so we can understand how life works," says Kress.

The genome project and seed banks have two distinct but complementary goals

"We're learning how an organism functions. When we have the whole genome we can identify the genes that control flowering, fruiting, seed production, drought tolerance and all these things that help the plant survive in its native habitat.

DNA starts to degrade within three minutes of an organism's death. Plant samples have to be immediately frozen in canisters of liquid nitrogen before being transferred to permanent storage.

A growing international network of cryo-storage facilities is taking part in the Global Genome Initiative. There are 25 so far on every continent except Antarctica. The tanks containing the world's largest natural history genome collection are operated by the Smithsonian at a centre in Maryland. It's capable of holding more than four million samples.

Jonathan Coddington, director of the Global Genome Initiative, says genomes are vital to understanding zoonotic diseases, identifying new species and advancing medicine. One in four prescription drugs already contains materials isolated from plants.

"There is a worm that can regenerate from just one cubic millimetre of tissue. Think about spinal injuries and how much pain that causes humans. This worm can grow an entire body - how does it do that? There's a jellyfish that's immortal. What is its secret? Life is filled with mysteries like this and the mysteries are fundamentally coded in their genes," he says.

"We also need to be able to track what climate change does to ecosystems in real time. To do that we have to scale it up and make it into big data. To do that, we need the genetic signatures of all the important species in those ecosystems so we can monitor them. The more we understand about change, the better we can cope with it."

Scientists are racing against the clock to save genetic evidence from plants around the world.

It's only recently that scientists have had the technology - and the financing - to embark upon such an extraordinary task. In 2001 genome sequencing cost around $95m (£61.2m). Today, sequencing can be carried out for $600,000.

Of the world's estimated 11 million species, only two million have been documented, and only 1% of the planet's known genomes have been sequenced.

The drive to collect plant genomes is being launched at three gardens in the Washington area - the US Botanic Garden, the National Arboretum and the Smithsonian Gardens. The samples will be taken mainly by volunteers - so-called "citizen scientists".

"We are giant collectors, hoarders of plants, and it's amazing the plant diversity we manage to keep within our walls," says Ari Novy, executive director, US Botanic Garden.

"Botanical institutions such as ours have spent decades and in some cases centuries collecting plants. The US Botanic Garden has almost 250 families which is half the total number of plant families on the planet. That makes this project a lot easier."

Many of the species are being sampled from the US Botanic Garden and the US National Arboretum

Some genomes can only be collected from cultivated plants because they are effectively extinct in the wild.

Brighamia insignis, nicknamed "cabbage on a stick" is a critically endangered species found in Hawaii. The plant can no longer reproduce on its own because its only pollinator was a certain type of hawk moth that is now extinct.

The US Botanic Garden is one of the few places where it is now grown and artificially pollinated. But with the combination of live plants and future technologies enabled by genome collection, it may one day thrive in the wild.

"These genomes will be preserved forever," says Coddington. "We're putting life on ice."

Video by Colm O'Molloy

- Published8 July 2015

- Published1 April 2015

- Published20 May 2015

- Published14 April 2015