For crime reporters a story of violence becomes personal

- Published

How do you report on your colleagues' death?

Crime reporter Nadine Maeser knows how to cover a shooting. But as she and her colleagues at WDBJ television discover, it's different when the victims are your friends.

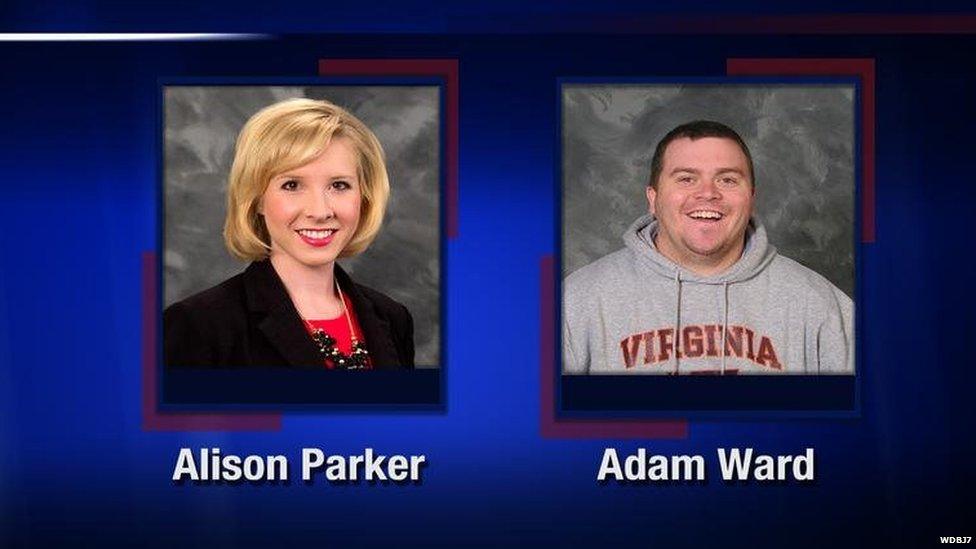

Adam Ward was funny - and generous. "If he was doing a live shot in the rain with you," she says. "He would take off his jacket and give it to you." Ward, a 27-year-old cameraman for WDBJ in Roanoke, Virginia, was gunned down on Wednesday on live television.

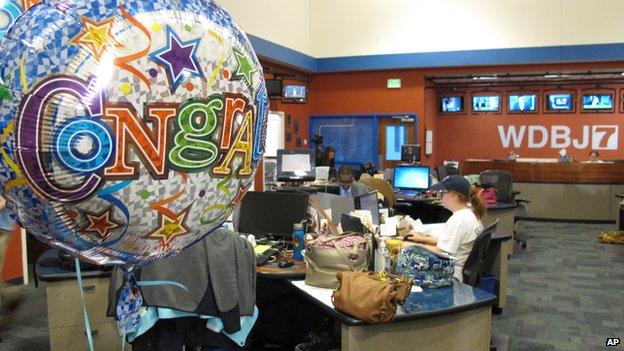

His fiancee, Melissa Ott, a WDBJ producer, was watching from a control room.

Thomas Milam, Steve Grant, Kimberly McBroom and Leo Hirsbrunner observe a moment of silence in the studio

They were going to be married in Charleston, South Carolina, Maeser says. She was the bridesmaid. The dress, she says, is blue and teal.

Hours after the shootings, she and her colleagues have ventured outside the building where they work to talk with journalists in the parking lot. At the same time she and her colleagues have managed to carry on with their duties as journalists. "We're on the air right now," she says. "We still had to cover the news."

One of the staples of local TV is crime reporting. Still the deaths of Ward and another colleague, Alison Parker, 24, have hit hard.

Maeser asks friends and colleagues to wear turquoise-and- maroon ribbon to commemorate the slain journalists

"It kind of makes you self-reflect on a lot of things that you do," Maeser says.

Across town in another studio Rick Moll, the news director of WSLS, says they were in shock about the shootings and that years of reporting on crime had done little to prepare them for the event. "If one bad guy does something bad to another bad guy, it's sort of like, you know, you report on it," he says, waiving his hand, dismissively.

Then his voice drops a notch. "You don't expect to be reporting on your colleagues being gunned down," he says.

Right now the task is relatively straightforward: carry on. Maeser and others at WDBJ agree they want to do their jobs in the way that Ward and Parker did - with discipline and professionalism. People are counting on them.

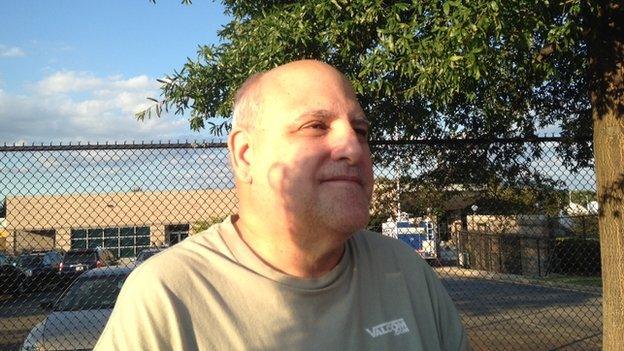

Bill Hurd, a printed circuit-board designer, says he's been watching the news programme for decades

Local TV journalism is a peculiarly American phenomenon. Local newscasters are "micro-celebrities", says John Carlin, the lead news anchor at WSLS 10, in their studio.

Newscasters at local stations are beloved in their communities, and people see them as members of their own family.

The feeling is mutual, since the loyalty of audience members has helped keep newscasters in business. Despite chaos in the US media market, local TV news is holding its own. Morning viewership went up last year, according to an April report, external from the Pew Research Center in Washington.

US audiences are devoted to local news anchor such as WSLS' John Carlin, shown on the left in a Roanoke studio

Viewers are drawn to the coverage of local issues, ranging from crime to "the need for a traffic light by the school", as Martin Mayer writes in About Television. The book is sitting on a shelf above an electric fireplace in the WSLS 10 studio.

This week Carlin and others who work in local television, a group of friendly rivals, have banded together as they mourn the deaths of Ward and Parker. The WSLS journalists share material on the day of the shootings, sending tapes to their WDBJ colleagues across town, and try not to cry on the air.

In the meantime a sense of solidarity is felt among the journalists, students and others who gather in the car park of WDBJ.

"Do you guys need anything - batteries or anything?" a cameraman from another rival station says to WDBJ's Allen Francis, who's doing a live shot. The cameraman pats Francis on the shoulder.

The deaths of Adam Ward and Alison Parker have hit their colleagues hard - yet they're still working

Many of the journalists were at work when they heard about the shootings. "You could probably hear us screaming from the building," says WDBJ's Justin Ward, who's not related to the victim.

Their boss, Jeffrey Marks, the general manager of WDBJ, says they continued to work that day - and he offered some guidance. "This was a story we didn't need to be first on," he says. "We need to be right."

As journalists check their equipment in the car park next to the WDBJ building, they talk about Ward and Parker and the way they did stories about crime.

"We have the same approach," says a WDBJ reporter, Shayne Dwyer. "Tell a story. I want you to take me there. I don't want to tell you the line: there's a robbery. Tell me what happened."

WDBJ Reporter Danielle Staub spoke about their slain colleagues with other journalists

Standing near a heap of flowers, bibles and stuffed animals under a tree, he says he considers his colleagues to be "family". For her "TV family", Maeser wrote on Facebook, external, she's made turquoise-and-maroon ribbons to commemorate their slain colleagues.

Their TV family is an extended one, including many people in the community.

"You welcome them into your homes every morning," says Samantha Roberts, 19, a recent graduate of Northside High School. "They always brought - like - joy." She places a ceramic pot of white roses under the tree.

Bill Hurd, 65, a printed circuit-board designer, says Parker and her colleagues were "just plain spoken - nothing fancy".

Nadine Maeser was preparing for Adam Ward's wedding to producer Melissa Ott (her desk is shown)

He says he's been watching WDBJ newscasters on television since he was a child. "They'd report on road conditions, traffic conditions," he says. "They worked for the local people."

The sense of community - and shared purpose - is felt by others who work in local news. They're all struggling to come to terms with the abrupt violence. Becky Freemal, an anchor for a Fox programme in Roanoke, seems preoccupied (to say the least) during a newscast after the shootings.

"Can you say I'm not going to say, 'Good-night', either?" she says, sitting in the studio and talking to her colleagues. "I'm just going to end on condolences."

She talks about the shootings at the end of the broadcast. "Our hearts out to the recent victims," she says. When the programme ends, she lets out a sigh. "Get me off the set," she says to no-one in particular.

She walks to the side of the room. As she's taking off her mic, she tells me she couldn't bring herself to say good-night. She looks at the ground. "There's just nothing good about it," she says.

For her and others it's been a hard day - maybe the toughest in their professional lives. Still the work helps, particularly among those setting up cameras and holding onto microphones in the WDBJ parking lot.

"Alison and Adam would have wanted us to be here," says Maeser, looking at her colleagues. "And, yeah, it's not a good time to be alone."

- Published27 August 2015

- Published26 August 2015

- Published27 August 2015

- Published26 August 2015