An act of extraordinary, underwater DIY

- Published

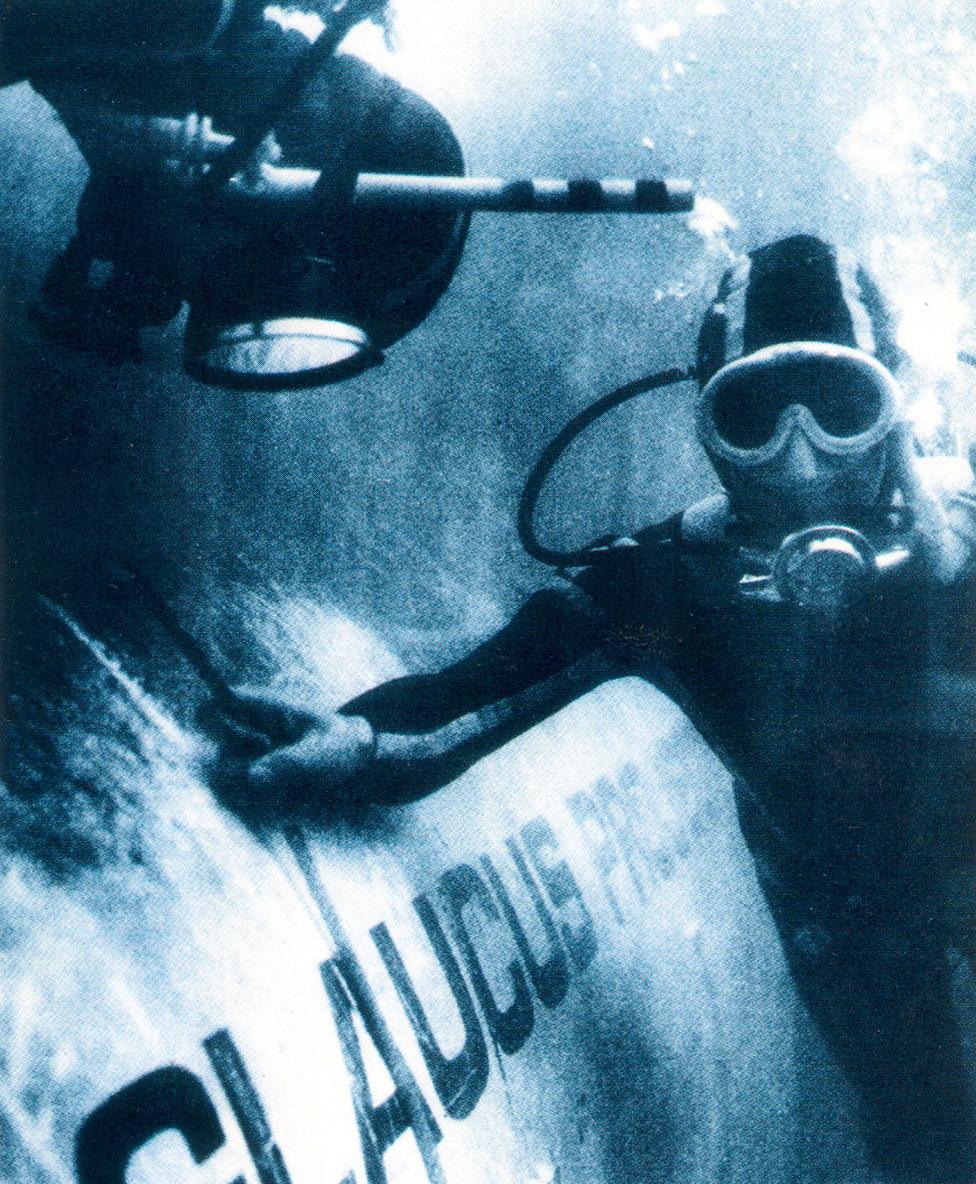

Diving outside the Glaucus capsule

Fifty years ago, two young diving enthusiasts undertook an extraordinary act of DIY, building a capsule in which they could live at the bottom of the sea. It was a symbol of an optimistic age.

The Breakwater Fort has stood guard at the mouth of Plymouth Sound for almost 150 years.

Its forbidding stone walls have seen a lot of maritime history, but perhaps no episode more intriguing than the Glaucus Project.

It was September 1965. The Sixties were swinging. The Rolling Stones were at number one. The world was changing and anything seemed possible.

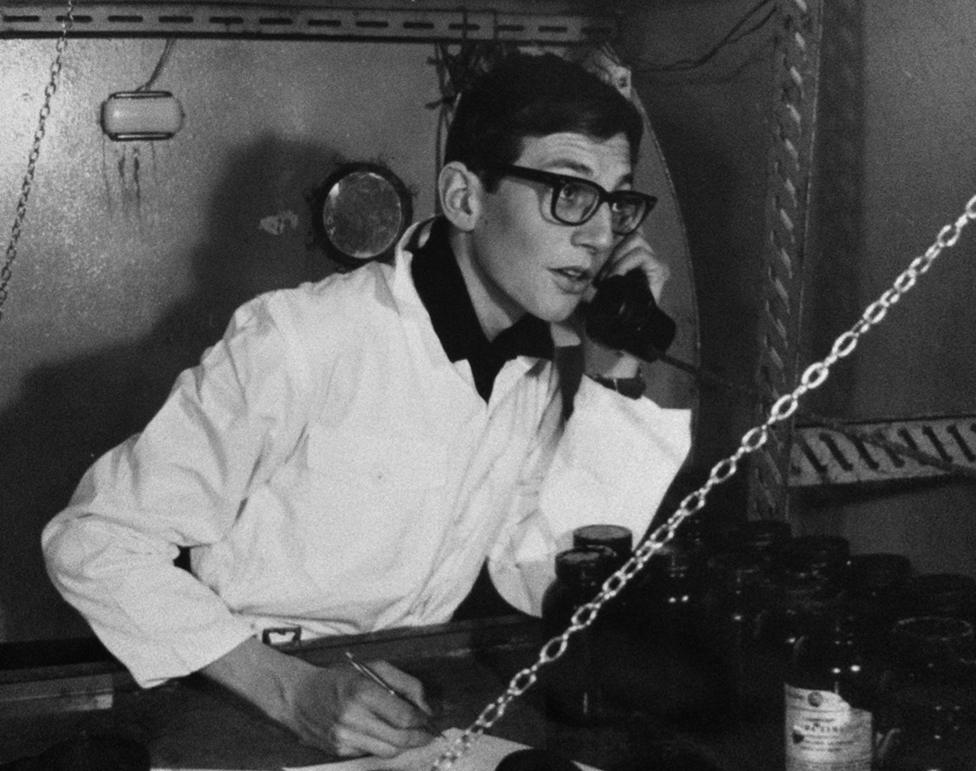

Colin Irwin, 19, and his friend John Heath, were both divers from Bournemouth and Poole Sub Aqua Club.

They were inspired by a series of big-money experiments in underwater living. Jacques Cousteau created three Conshelf - short for Continental Shelf Station - underwater habitation and research stations at a depth of 100m (328ft) and funded by the French oil industry. The American Navy's SEALAB I, on the seabed off the coast of Bermuda at a depth of 58m, held four divers for 11 days until an approaching storm cut the project short.

Colin Irwin in 1965

The two young British divers decided to have a go themselves.

Irwin, now 69, was convinced it was the way forward: "We all thought at the time, 'Well, this is the future. We may not populate the Moon, but we're going to have villages all over the continental shelf, and we thought it's about time the British did the same thing'."

It took months of work to scrape together the £1,000 budget to build the Glaucus habitat.

"One of the club members, his dad owned a shipyard, so we had someone who could actually make the underwater house on the cheap. So we were able to put it all together and get the job done," says Irwin.

Revisiting the story of the divers who experimented with living at the bottom of Plymouth Sound in the Glaucus pod 50 years ago.

Documents and letters from the time, though, show how tight the money was. The team had to beg the company supplying them with oxygen to let them have it for nothing.

But it was that shoestring budget that earned Glaucus its place in history.

Where Cousteau and the US Navy had been able to use huge compressors to pump oxygen down into their habitats, Irwin and his team simply could not afford that.

Their solution was a world first.

"We had to analyse the atmosphere, see what the oxygen level was, what the carbon dioxide level was and put out soda lime to absorb the CO2 and top it up with oxygen bottles. So by virtue of economics, we became the first underwater home with a self-contained atmosphere," says Irwin.

The Glaucus was towed into place on 19 September by a tugboat and lowered 11m down between the Breakwater and the Fort, where the waters would be calmer.

Divers outside the Glaucus habitat

The finished habitat was a cylinder tank, made of steel, which weighed in at two tonnes and was 3.7m long and 2.1m high - just enough room to walk around.

Once Irwin and Heath were inside, they kept in contact by phone to a team stationed on the fort but apart from that, they were on their own.

Quarters were close, it was very cold and 100% humid - and the tank was open to the sea at the bottom through a hatch.

Irwin remembers it was quite a change from a normal dive. "What was psychologically different about it was that normally if you get into trouble, you want to get up to the boat or dry land. But after we'd been down there 24 hours, we were on what's called a full saturation dive. Our fatty tissues were full of dissolved nitrogen. If we'd made an emergency ascent, we'd have got the bends."

The Glaucus being winched into Sutton Harbour

Nipping out for a "number two" toilet break was something of a challenge. The aquanauts had to restrict themselves to only going every couple of days as they had to go through a hatch to a separate compartment, so their living area wouldn't get contaminated.

Luxury living it was not - but they survived the week.

It's an achievement that is still respected, says Dr John Bevan, chairman of the Historical Diving Society, who runs the National Diving Museum in Gosport.

"It's the fact that it was an amateur experiment, and so successful, in terrible conditions. It wasn't the Mediterranean or the Red Sea or California. It was cold and damp and probably the most difficult of all the underwater living experiments."

Back on dry land, Colin Irwin started work on designing a larger capsule and tried to find funding from the government and industry.

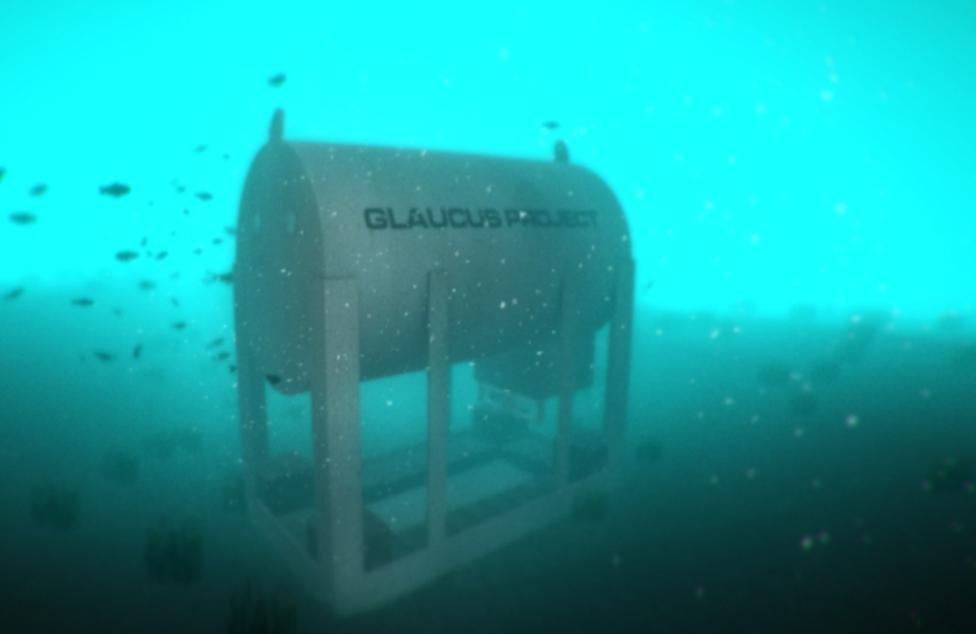

The Glaucus habitat

Metal cylinder weighing 1.8 tonnes, and measuring 3.7m, and 2.1m in diameter

Ballasted with pig iron and sections of railway line, weighing some 14,000kg

Container included a foldable table and two bunks, giving aquanauts free floor space of 2m x 1.4m

But what the Cousteau and American experiments had showed was that the dream of creating underwater living was too expensive and risky. The '60s dream of underwater villages alongside dry land started to fade.

Irwin himself moved on to develop a career promoting peace around the world, working in Northern Ireland and the Middle East. He now works at Liverpool University but has lost touch with his fellow aquanaut John Heath.

The Glaucus capsule itself came to a rather sad end. It now lies just off the Breakwater Fort about 13m below the surface where it's quietly rotting, listing on its remaining legs.

Divers regularly go down to see it for themselves, and Colin himself went back for the first time over the summer with the BBC's Inside Out South West.

The underwater home can't be salvaged now as it is too badly damaged but it has been given a new lease of life.

Irwin looks at a recreation of the Glaucus through a virtual reality headset

The Human Interface Technologies Team at the University of Birmingham has been working for some time on creating a virtual reality seascape of Plymouth Sound, the final resting place of many wrecks.

The latest addition to this Virtual Heritage is a computer-generated dive down to, and inside, the Glaucus itself.

Prof Bob Stone, from the university's Human Interface Technologies Team, is leading the project.

"We're going for realism with this project," he says. "We can get very detailed images indeed especially with the games technology we're using. So we can simulate turbid water, particles in the water, lighting effects underwater."

It has been a long and painstaking process to build the virtual reality. Bob's team used the original plans, as well as high-definition close-up and aerial photographs of the Breakwater, and sound recordings to make the recreation as realistic as possible.

"We're hoping eventually to put the simulation on a smartphone or tablet or to download as an app to show schoolchildren, particularly those in Plymouth who've got no idea that this kind of history is on their doorstep."

Colin Irwin visited Birmingham to take the first virtual trip down memory lane.

"They've got it spot on, the height, the dimensions. At one point I put my hand out to brace myself as I was getting up from the virtual reality hatch and, of course, there was nothing there."

The Glaucus itself may have come to a watery end - something Irwin regrets - but thanks to some technological wizardry, perhaps a little bit of that pioneering spirit lives on.

More from the Magazine

Underwater hideouts may be the domain of James Bond villains and Gerry Anderson's Stingray puppets but people in the real world are also dreaming about living at the bottom of the sea - and the dreams may not be far off being realised, writes marine biologist Helen Scales.

Inside Out South West is on BBC One on Monday, 7 September at 19:30 BST and nationwide on the iPlayer for 30 days thereafter.

Subscribe to the BBC News Magazine's email newsletter, external to get articles sent to your inbox.